What you need to know about blood sugar

Maybe you bought a blood sugar meter because you’ve been given a concerning diagnosis of pre-diabetes or diabetes. Or maybe one of these conditions runs in your family. Perhaps you’re just curious to know what food does to your blood sugar — and willing to sacrifice a few drops of blood to find out.

If you’re new to testing your blood sugar, rest assured that it’s simple to do.

Whether you’re experienced at it or not, testing your blood sugar can help you better identify which dietary changes lower your blood sugar over time. It can also help you identify specific foods that raise blood sugar.

1. Getting started

Many different blood sugar meters (also known as glucose meters or glucometers) are available, and most of them are fairly inexpensive.

However, make sure that the test strips for your meter are affordable and available. The real cost of blood-sugar testing lies in the cost of the strips, which can only be used once and expire after a certain date.

In addition to a meter and strips, you’ll need a lancet, which contains a short, small needle that will prick your finger quickly and (almost) painlessly. Lancets are very inexpensive and are discarded after each use. Most blood sugar meters come with a lancet and about a dozen replacement needles.

How to measure blood sugar

You should read the directions that come with your blood sugar meter and follow those carefully. For most meters, the general procedure goes like this:

- With clean hands, place a test strip in your blood sugar meter.

- Prick the side of a finger with the lancet to draw a drop of blood.

- Place the tip of the test strip on the drop of blood.

- After a few seconds, the blood sugar meter will give you a reading.

Many blood sugar meters will keep track of your blood sugar readings for a number of days or weeks. Even if your meter stores these readings, it may be a good idea to record the date, time, and other information to share with your healthcare provider or for your own purposes. Use a notebook, computer spreadsheet program, or app to keep track of your readings.

When to measure blood sugar

If your healthcare provider has given you specific instructions about when to test your blood sugar, you should follow those instructions.

Many people check their blood sugar first thing in the morning, before eating. Because no food has been consumed for at least 8-10 hours, a blood sugar measurement at this time of day is called a “fasting blood sugar.” It’s best to check this at the same time every day.

You can also check your blood sugar right before eating (a pre-meal or preprandial level) or after a meal (a post-meal or postprandial level). If you’ve been instructed to check your blood sugars at a specific time interval after a meal, you should begin timing once you start eating.

2. What is a normal blood sugar?

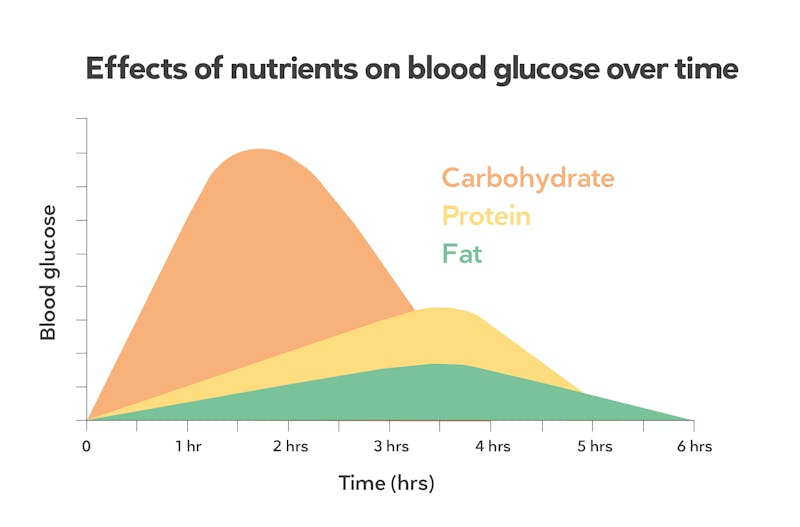

Ideas about “normal” blood sugar levels are based on individuals eating a standard American diet. This type of diet usually contains about 50% of calories from carbohydrate, the nutrient that tends to raise blood sugar the most.

If your own carbohydrate intake is much lower than this, you may have a different “normal.” You can jump to How a low-carb diet affects blood sugar measurements for more information.

Fasting blood sugar levels

A normal fasting blood sugar level in someone who does not have diabetes is generally between 70 and 100 mg/dL (3.9 to 5.6 mmol/L).

Fasting blood sugar that consistently falls in the range of 100 to 125 mg/dL (5.6 to 6.9 mmol/L) is considered prediabetes, which is also referred to as impaired fasting glucose.

If your fasting blood sugar is above 126 mg/dL (7.0 mmol/l) on two separate occasions, then you may have diabetes.

If you are concerned about the measurements you’re getting, especially if you are already on a low-carbohydrate diet, see How a low-carb diet affects blood sugar measurements. A few blood sugar measurements may not always provide an accurate picture of your health.

Post-meal blood sugar levels

If your healthcare provider has not given you specific instructions regarding when to test post-meal blood sugar, you may want to try measuring it one to two hours after you begin eating. Whichever reading is the highest is the one that you should pay attention to, because blood sugar levels may peak at different times.

How much and how quickly your blood sugar level increases after eating is mainly determined by your body’s ability to handle carbohydrates.

In people who don’t have diabetes, blood sugar levels typically peak about an hour after starting a meal.

According to the American Diabetes Association, a normal post-meal blood sugar reading one or two hours after a meal is below 140 mg/dL (7.8 mmol/L).

If your blood sugar is consistently 140 mg/dL (7.8 mmol/L) or higher but less than 200 mg/dL (11.1 mmol/L) when measured two hours after beginning a meal, you may have prediabetes or impaired glucose tolerance.

If your blood sugar measurements are consistently 200 mg/dL (11.1 mmol/L) or higher two hours after beginning a meal, you likely have diabetes.

If your fasting or post-meal blood sugar levels are consistently higher or lower than normal, you may have a medical condition that requires a visit to a healthcare provider.

However, if your blood sugar levels suddenly go from “normal” to “not normal” when you get a new meter or a new container of test strips, check your meter and strips to ensure they’re taking accurate measurements. When a result is very different than expected, take three measurements and use the average of the three.

Blood glucose chart

Each measure should be done on at least two separate occasions before you suspect that your blood sugars are too high or too low. See your healthcare provider about any concerns you may have about your blood sugar readings

3. What to do if your blood sugar levels are lower than normal

Blood sugar levels that are below 70 mg/dL (3.9 mmol/L) are known as hypoglycemia. Symptoms of hypoglycemia include heart palpitations and feeling lightheaded, jittery, irritable, fatigued, or sweaty.

Low fasting blood sugar levels can occur if you have diabetes and your medication does not match your carbohydrate intake. So it’s very important to let your healthcare provider know you’re following a low-carb diet so they can adjust your medication to match your carb intake.

In people who do not have diabetes, low fasting blood sugar levels are very rare. But if low blood sugars do occur they may be the result of a serious underlying medical condition such as an eating disorder or a tumor. If your fasting blood sugar is low and you do not take diabetes medications, see your healthcare provider.

Low blood sugar levels after eating are often called reactive hypoglycemia. This can occur in people with diabetes, as well as those with normal fasting blood sugars. How it should be treated depends on what the underlying cause is. But if you have low blood sugar and experience symptoms, you can remedy this in the short term by eating something with carbs or sugar.

High-carb intake may cause reactive hypoglycemia in people who are very insulin sensitive or have experienced massive weight loss.

4. What to do if your blood sugar levels are higher than normal

If your fasting or post-meal blood sugar readings are consistently higher than normal, you may have prediabetes or diabetes. If you suspect you have diabetes or prediabetes, you should see your healthcare provider as soon as possible.

Symptoms of diabetes, beyond elevated blood sugars, may include increased thirst and urination, severe fatigue and excessive hunger. For more details, see our guide to common signs and symptoms of diabetes.

5. Personalizing your diet based on blood sugar response

In addition to seeing your healthcare provider, there are steps you can take to reduce your blood sugar levels. If you check your blood sugar after meals and keep track of those measurements, along with the types and amounts of food you ate, you may be able to see which foods are problematic.

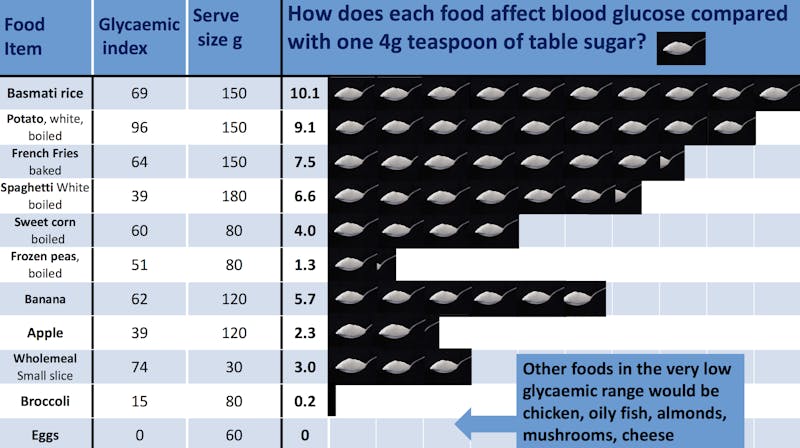

Although an increase in blood sugar is usually due to eating high-carb foods, all carbs are not the same when it comes to raising blood sugar. Because starchy foods digest down to glucose (sugar) very quickly, some starchy foods may end up having a much greater impact on blood sugar than you might expect.

For instance, even though a banana tastes sweeter than a baked potato, the potato may actually have a bigger impact on blood sugar.

Because high-carb foods have the biggest impact on blood sugar levels, it makes sense to reduce them, no matter what type of diet you follow. The American Diabetes Association made this point in a 2019 paper on nutrition for people with diabetes.

Sometimes making gradual changes can work best. Our guide, Eating better: six steps down carb mountain, can help you lower your carb intake, one step at a time.

If you’ve been diagnosed with type 1 or type 2 diabetes, our guide to the best foods for people with diabetes can help you make choices that may reduce your need for blood sugar control medications.

Other foods that are low in carbs may also increase blood sugar response. For example, in one study when caffeinated coffee was consumed with meals containing either rapidly digested or slowly digested carbs, blood sugar levels were higher than they were after the same meals without caffeine.

If a food or beverage seems to be causing your blood sugar to rise too much, try leaving it out of your diet for a few days to see if you notice a difference.

6. Other ways to measure blood sugar

Checking your blood sugar levels with a glucometer is not the only way to measure blood sugar. Other tests that your healthcare provider might use to check your blood sugar levels are hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) and oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT). Perhaps the most helpful data comes from a continuous glucose monitor (CGM). You can learn more about CGMs in our evidence-based guide.

HbA1c provides an estimate of your average blood sugar levels over time, giving you a sense of your blood sugar control over the last two or three months. An HbA1c test is one of the most common measurements used for diagnosing type 2 diabetes.

However, HbA1c tests and blood sugar tests don’t always agree. Using HbA1c levels to diagnose diabetes often fails to identify individuals who would otherwise be diagnosed with diabetes using blood sugar levels.

Your HbA1c is normal if it is below 5.7%. You may have prediabetes if your HbA1c is above 5.7% but less than 6.5%. You may have diabetes is your HbA1c is 6.5% or over.

| HbA1c | |

| Normal | less than 5.7% (38.8 mmol/mol) |

| Prediabetes | 5.7% to 6.4% (38.8 to 46.4 mmol/mol) |

| Diabetes | 6.5% (47.5 mmol/mol) or higher |

| “Cautious” approach | Less than 5.4 % (36.0 mmol/mol) |

To learn more about HbA1c measurements and how they relate to blood sugar levels you record with your glucometer, see our full guide to understanding HbA1c.

An oral glucose tolerance test (sometimes referred to as an OGTT) can be more accurate in terms of diagnosing prediabetes or diabetes.

A continuous glucose monitor (CGM) is a wearable device that, as the name says, continuously measures blood glucose levels. Although they may be more expensive than glucometers and more challenging to get covered by insurance, they’re a helpful way to measure blood sugar throughout the day. CGMs allow you to easily see post-meal variations and get an average blood sugar level for the day.

7. How a low-carb diet affects blood sugar measurements

If you are on a low-carb diet, you may find that some ways of measuring blood sugar will not provide you with “normal” levels.

For example, fasting blood sugar levels may be slightly above normal. This may be due to “adaptive glucose sparing” and “the dawn phenomenon.”

If you are concerned about these levels, consider asking your healthcare provider for a more detailed evaluation including an HbA1c or CGM.

If you’re on a low-carb diet, your HbA1c will likely be lower than your fasting blood sugar levels would predict, since your blood sugar probably doesn’t increase much after meals.

For people who have been on a low-carb diet for a long time, an OGTT may mistakenly diagnose you as having diabetes. Because your body is fat adapted and no longer using sugar as its main fuel, you may have an exaggerated blood sugar response to the glucose drink. If that occurs, you may fail the test and be given a diabetes diagnosis when you actually do not have the condition.

If your doctor orders an OGTT test and you want to take it, you may want to start consuming more carbs about three days before the test.

Conversely, if you are on a ketogenic diet and have elevated ketones, your blood sugar may naturally be 70 mg/dL (3.9 mmol/L)or slightly below. In this case, because ketones are fueling your body, you likely won’t have typical symptoms of hypoglycemia, such as shakiness or lightheadedness.

Checking blood sugar can be a simple way to learn the effects various foods have on your body. However, it’s important to remember that your blood sugar level, like your weight, is just a number. Panicking when your fasting blood sugar is 102 mg/dL (5.7 mmol/L) one morning adds extra stress to your day, which isn’t beneficial to your health!

Use your glucometer wisely, as another tool in your toolbox on your health journey.