Nina Teicholz’s best-seller “The Big Fat Surprise”: How the low-fat diet was introduced to America

Are you ready for The Big Fat Surprise?

Nina Teicholz’s bestselling book about the mistakes behind the fear of fat reads like a thriller. It was named one of the best books of the year by a number of publications (including the #1 science book by The Economist).

All the inconvenient attention has made Teicholz’s name sound like Voldemort to fragile egos in the nutritional world.

If you have not read it yet we have a treat for you. Teicholz has agreed – for the first time – to share several sections of the book with the readers of Diet Doctor.

Here’s the first of three sections, about how the low-fat diet was introduced to America, and Ancel Keys’ magic year of 1961:

The Low-Fat Diet Is Introduced to America (BFS p.47)

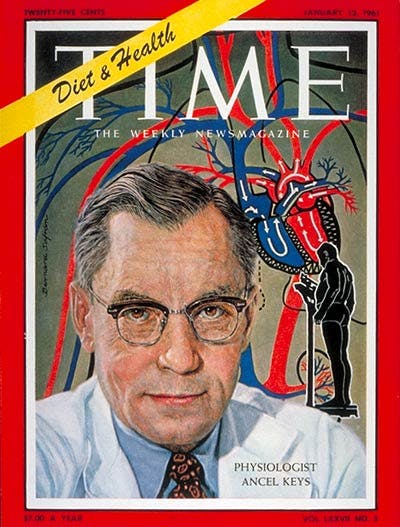

…The year 1961 was an important one for Ancel Keys and his diet-heart hypothesis. He managed three significant coups: one within the American Heart Association, the most powerful heart disease group in US history; another on the cover of Time magazine, the most influential magazine of its day; and the third at the National Institutes of Health, which was not only the leading scientific authority in the land but also the richest source of research funds. These three groups were the most important actors in the world of nutrition, and as a bias in favor of the diet-heart hypothesis settled in among them, they operated like a tag team, institutionalizing Keys’s ideas and conveying them onward and upward for decades to come.

The AHA alone was like an ocean liner steaming the diet-heart hypothesis forward. Founded in 1924 at the outset of the heart disease epidemic, the group was a scientific society of cardiologists seeking to better understand this new affliction. For decades, the AHA was small and underfunded, with virtually no income. Then, in 1948, it got lucky: Procter & Gamble (P&G) designated the group to receive all the funds from its “Truth or Consequences” contest on the radio, raising $1,740,000, or 17 million in today’s dollars. At a luncheon, P&G executives presented a check to the AHA president, and “suddenly the coffers were filled and there were funds available for research, public health progress and development of local groups — all the stuff that dreams are made of!” according to the AHA’s of- cial history. The P&G check was the “bang of big bucks” that “launched” the group. Indeed, one year later the group opened seven chapters across the country and collected $2,650,000 from donations. By 1960, it had more than three hundred chapters and brought in more than $30 million annually. With continued support from P&G and other food giants, the AHA would soon become the premiere heart disease group in the United States, as well as the largest not for profit group of any kind in the country.

The new funds in 1948 allowed the group to hire its first professional director, a former fund-raiser for the American Bible Society, who unfolded an unprecedented fund-raising campaign across the United States. There were variety shows, fashion shows, quiz programs, auctions, and collections at movie theaters, all meant to raise money and let Americans know that heart disease was the country’s number one killer. By 1960, the AHA was investing hundreds of millions of dollars in research. The group had become the authoritative source of information about heart disease for the public, government agencies, and professionals alike, including the media.

Because diet was considered a probable cause of heart disease, the AHA in the late 1950s pulled together a committee of experts to develop some advice about what a middle-aged man ought to eat as a measure of defense. President Eisenhower was already following a “prudent” diet to battle his condition under the supervision of AHA founder Paul Dudley White. The fact that White’s care had allowed Eisenhower to get back to work in the Oval Office was itself of great significance to the AHA, since it showed that the group had advice worth following. It helped, too, with fund-raising: after Eisenhower’s heart attack, the AHA took in 40 percent more in donations than it did the year before [1].

The newly formed AHA nutrition committee acknowledged that the average doctor faced a great deal of pressure to do something: “People want to know whether they are eating themselves into premature heart disease,” the committee wrote. It nevertheless resisted this pressure and published a cautious report. The evidence, it stated, could not even reliably say whether high cholesterol in any given person would predictably lead to a heart attack, so it was too soon to be telling Americans to make any “drastic” dietary change toward this end. ( e committee did, however, recommend reducing fat to between 25 percent and 30 percent of calories for people who were overweight because this would be a good way to cut calories.) Committee members went so far as to rap diet-heart supporters like Keys on the knuckles for taking “uncompromising stands based on evidence that does not stand up under critical examination.” The evidence, they concluded, did not permit such a “rigid stand.” [2]

However, a significant shift in AHA policy came a few years later, when Keys, together with Jeremiah Stamler, a doctor from Chicago who became his ally, maneuvered themselves onto the nutrition committee. Although some critics noted that neither Keys nor Stamler had been trained in nutrition science, epidemiology, or cardiology, and although the evidence for Keys’s ideas had not grown any stronger since the AHA’s previous position paper on nutrition, the two men managed to convince their fellow committee members that the diet-heart hypothesis should prevail. The AHA committee swung around in favor of their ideas, and the resulting report in 1961 argued that “the best scientific evidence available at the present time” suggested that Americans could reduce their risk of heart attacks and strokes by cutting the saturated fat and cholesterol in their diets.

The report also recommended the “reasonable substitution” of saturated fat with polyunsaturated fats such as corn or soybean oil. This so-called “prudent diet” was still relatively high in fat overall. In fact, the AHA would not stress the reduction of total fat until 1970, when Jerry Stamler steered the group in this direction. For the first decade, however, the group’s focus was primarily on reducing the consumption of the saturated fats found in meat, cheese, whole milk, and other dairy products. The 1961 AHA report was the first official statement by a national group anywhere in the world recommending that a diet low in saturated fats be employed to prevent heart disease. It was Keys’s hypothesis in a nutshell.

This was a huge personal, professional, and ideological triumph for Keys. The influence of the AHA on the subject of heart disease was — and still is—unparalleled. For scientists in the field, the chance to serve on the AHA nutrition committee is a highly sought-after plum, and from the start, the dietary guidelines published by that committee have been the gold standard of nutritional advice. These guidelines are influential not only in the United States but around the world. Thus Keys’s ability to insert his own hypothesis into these guidelines was like splicing DNA into the group: it programmed the AHA’s growth, and as it grew, the group has in turn served as both rudder and engine for Keys’s diet-heart ship over the past half-century.

Keys himself thought that the 1961 AHA report he had helped write suffered from “some undue pussy-footing” because it had prescribed the diet only for high-risk people rather than the entire American population, but he need not have complained too much. Two weeks later, Time magazine featured the fifty-seven-year-old Keys on its cover, bespectacled and dressed in a white lab coat, with a heart drawn in behind him sprouting veins and arteries. Time called him “Mr. Cholesterol!” and quoted his advice to cut dietary fat from its current average of 40 percent of total calories down to a draconian 15 percent. Keys advised an even sterner cut for saturated fat — down from 17 percent to 4 percent. These measures were the “only sure way” to avoid high cholesterol, he said.

The article dwelled on the diet-heart hypothesis at length, as well as Keys’s personal history: he was depicted as unbridled and sharp, but in a way that commands authority. He was the man with the harsh medicine: “People should know the facts,” he said. “then, if they want to eat themselves to death, let them.” Keys himself, according to the article, seemed barely to follow his own advice; his “ritual” of dinner by candlelight and “soft Brahms” at home with Margaret included meat—steak, chops, and roasts—three times a week or less. (He and Stamler were also once spotted by a colleague at a conference tucking into scrambled eggs and “five or so rations” of bacon.) “Nobody wants to live on mush,” Keys explained. In the Time article, there is only a brief mention of the reality that Keys’s ideas were “still questioned” by “some researchers” with conflicting ideas about what causes coronary disease.

And here was the other engine moving the diet-heart hypothesis ship forward: the media. Most newspapers and magazines became persuaded by Keys’s ideas early on. The New York Times gave that front-page space to Paul Dudley White, for instance, and picked up on Keys’s views early on (“Middle Aged Men Cautioned on Fat” a headline read in 1959). Like the research community itself, the media was looking for answers to the heart disease epidemic, and dietary fat plus cholesterol made sense. Not only did Keys have a talent for publicity, but his fiery language and definitive-sounding solution were clearly more appealing to reporters than the dispatches from scientists such as Rockefeller’s Pete Ahrens, who cautioned soberly about the lack of adequate scientific evidence. The media also took its cue from the AHA, and soon after that group issued its “prudent diet” guidelines, the New York Times reported that the “highest scientific body has lent its stature” to the view that reducing or altering the fat content of a person’s diet could help prevent heart disease.

A year later, the New York Times gave an air of apparent inevitability to these new dietary patterns: “whereas people once thought of dairy products in terms of health and vitality, many people now associate them with cholesterol and heart ailments,” stated one article entitled “Is Nothing Sacred? Milk’s American Appeal Fades.” The media was nearly unanimous in its support of Keys’s hypothesis. Newspapers and magazines made his diet known nationwide, while women’s magazines carried it into the kitchen with recipes to cut back on fat and meat. Influential health columnists also helped spread the word: the Harvard nutrition professor Jean Mayer wrote a syndi- cated column that appeared twice weekly in one hundred of the largest US newspapers, with a combined circulation of 35 million. (In 1965, he called the low-carbohydrate diet “mass murder.”) And from the 1970s on, New York Times health writer Jane Brody became one of the greatest promoters of the diet-heart hypothesis. She reported faithfully on AHA pronouncements as well as any new studies linking fat and cholesterol to heart disease or cancer. One article she wrote in 1985 called “America Leans to a Healthier Diet” starts o featuring Jimmy Johnson, who “used to wake up to the smell of bacon in the pan,” while his wife remembered saving the bacon grease to then fry the eggs; now, said Mr. Johnson, “just a bit ruefully: ‘the smells are gone from breakfast, but we’re all a lot better off for it.’ ”

Journalists could paint a vivid picture and reach a broad audience, but they were not saying anything different from what health officials themselves advised. For the media and nutrition experts alike, the chain of causation that Keys had proposed seemed to make eminent sense: dietary fat caused cholesterol to rise, which would eventually harden arteries and lead to a heart attack. The logic was so simple as to seem self-evident. Yet even as the low-fat, prudent diet has spread far and wide, the evidence could not keep up, and never has. It turns out that every step in this chain of events has failed to be substantiated: saturated fat has not been shown to cause the most damaging kind of cholesterol to go up; total cholesterol has not been demonstrated to lead to an increased risk of heart attacks for the great majority of people, and even the narrowing of the arteries has not been shown to predict a heart attack. But in the 1960s, these revelations were still a decade away, and official institutions, along with the media, were already gathering enthusiastically behind Keys’s attractively simple idea. It seems they were convinced enough, moreover, that their eyes were already closing to evidence to the contrary.

It’s worth looking at some of the evidence they were ignoring, because although some scientific observations—most prominently the Seven Countries study — seemed to support the diet-heart hypothesis, a great many studies from those early years proved to be surprisingly uncooperative. We’ll take a tour through a handful.

More

Keep reading by ordering the book on Amazon

Top Nina Teicholz videos

- MEMBERS ONLY

![The myth of vegetable oils]()

- MEMBERS ONLY

![Why our dietary guidelines are wrong]()

- MEMBERS ONLY

![Can red meat kill you?]()

Footnotes

1. Eisenhower was extremely supportive of the AHA throughout his presidency: he presented the AHA’s annual “Heart of the Year Award” from the Oval Office, held opening ceremonies for the AHA’s “Heart Fund Campaign” in the White House, attended AHA board meetings, and assumed the AHA post of Honorary Chairman of the Future. Members of his cabinet also served on the AHA board. The AHA’s official historian concludes, “Thus, the top leaders of the United States government were active Heart campaigners” (Moore 1983, 85).

2. Other theories at the time that mainstream scientists seriously considered as the cause of heart disease included vitamin B6 deficiency, obesity, lack of exercise, high blood pressure, and nervous strain (Mann 1959, 922).