Vegetable oils: Are they healthy?

Vegetable oils — those shiny modern elixirs — have seeped their way into all the nooks and crannies of our food supply.

If you eat out, chances are your food is cooked in — or doused with — some type of vegetable oil. If you buy packaged goods like crackers, chips or cookies, there’s a very good chance that vegetable oils are in the ingredients list. If you buy spreads, dips, dressings, margarine, shortening or mayo, can you guess the likely star ingredient? Yup — vegetable oils.

Is this a good thing? To find out, let’s review what we know, and what we don’t know, about these plant-based fats.

Ready for a deep dive into this controversial issue? Click any of the links to jump to that section, or simply keep reading!

Because of inconsistent evidence of health benefits, potential negative health effects, concerns about the ultra-processed and unstable nature of many of these oils and due to evolutionary considerations, we believe that the conventional recommendations about vegetable oils deserve a more detailed analysis. Full disclaimer

Controversial topics related to vegetable oils, and our take on them, include saturated fats and cholesterol.

What are vegetable oils?

In a technical sense, vegetable oils include all fats from plants. However, in common usage, “vegetable oil” refers to the oil extracted from crops like soy, canola (rapeseed), corn and cotton.

Is olive oil a vegetable oil? What about palm oil and coconut oil? Technically, yes, these oils come from plants, so they are vegetable oils. But they originate from the fruit or nut rather than the seed and are easier to extract.1

These three traditional oils have been part of the food supply for thousands of years; today, they account for less than 15% of vegetable oil consumption in the US.2 More than half of the vegetable oils consumed in the US comes from just one crop: soybeans.3

For purposes of this post, we will narrow the meaning of vegetable oils to include only oils from the industrial oilseed crops: soybean, canola (rapeseed), corn, sunflower, cottonseed and safflower oils.

In addition, we will assume the vegetable oils we are discussing haven’t been hydrogenated. Partially hydrogenated vegetable oil products, like Crisco and margarine, were once marketed to Americans as “heart healthy.” Now we call them “trans fats,” which we are in the process of eliminating from our food supply due to their negative health effects.4

How are vegetable oils made?

Unlike olive oil that has been pressed for centuries, most vegetable oils require significant industrial processing.5

Heat, cold, high-speed spinning, solvents like hexane, degumming agents, deodorizers and bleaching agents are typically used to process the seeds into a palatable oil.6

For a visual rendition of this industrial process, check out this video that documents the production of canola oil.

Given the level of industrial work required to extract the oil, many modern vegetable oils are rightly classified as processed food products.

How much vegetable oil did we eat historically, and how much are we eating now?

Refined vegetable oils are the ‘new kid on the block’ in human diets.

Millions of years ago, the only vegetable fats our ancestors consumed likely came from wild plants.7 Around 4000 BC or earlier, pressed olive oil became a staple in the diets of people living in Italy, Greece, and other Mediterranean countries.8

The vegetable oils we know today were developed at the end of the 19th century, when technological advances allowed oils to be extracted from other crops.9

Around 100 years ago, there was very little vegetable oil in the food supply, and it did not form a significant part of the diet.10

The consumption of soybean oil increased more than 1,000-fold from 1909 to 1999.11 According to food availability data, by 2010, the amount of vegetable oil in the US food supply was 50 grams, or 11 teaspoons of vegetable oil each day per capita.

These data do not account for waste, however; consumption data suggest intake of linoleic acid (the major omega-6 fatty acid) is around 17 grams per day, about 7% of energy intake.12 Vegetable oil intake in total is probably twice this amount.

The dramatic increase in vegetable oil consumption is supported by data showing the rise in linoleic acid consumption is changing the fatty acid composition of the body’s cells.13

What types of fatty acids are in vegetable oils?

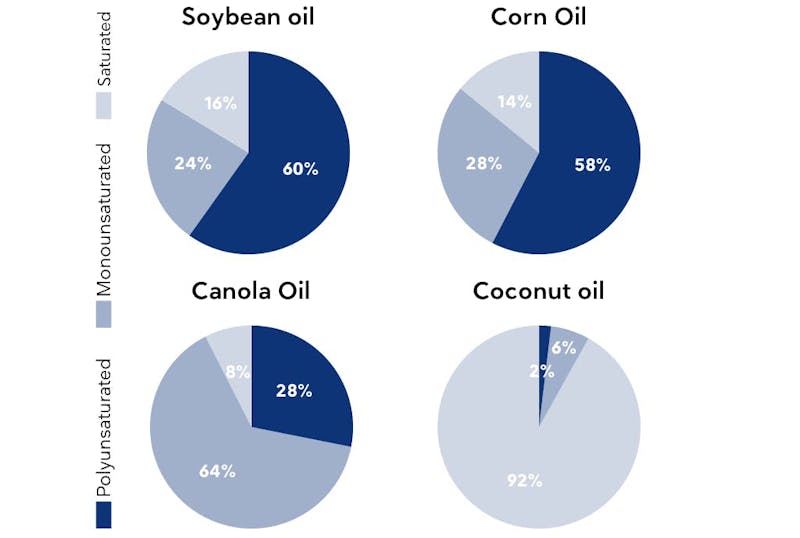

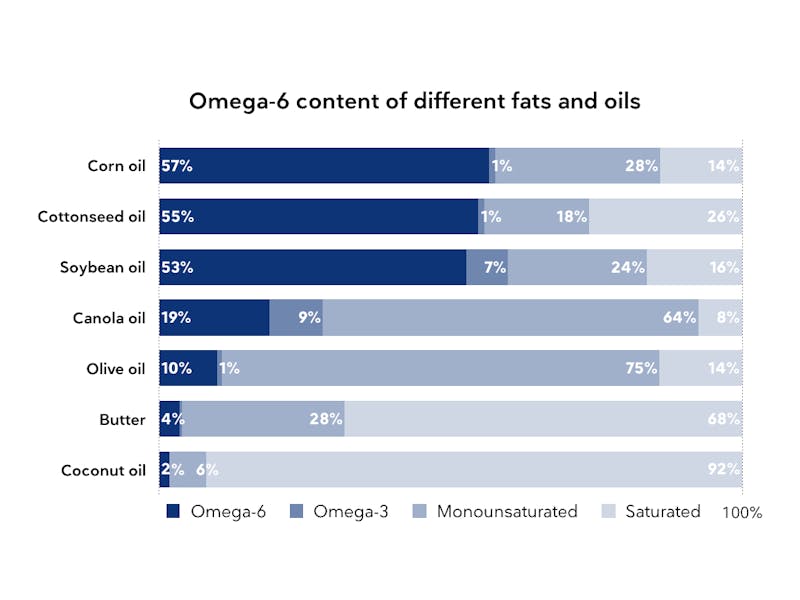

All fats contain a blend of saturated (SFA), monounsaturated (MUFA) and polyunsaturated (PUFA) fatty acids (learn more), and vegetable oils are no exception. Each type of seed has its own signature blend of the dozens of possible fatty acids that occur in nature, and each fatty acid is either a saturated, monounsaturated or polyunsaturated fatty acid.

Take a look at the percentage makeup of the three main vegetable oils in our food supply, compared to coconut oil, a traditional plant fat:

In addition, there are two other omega-3 fatty acids which can be made from alpha-linolenic acid: eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA). The conversion from ALA to EPA and DHA is generally poor, so getting EPA and DHA from foods or supplements is advised.

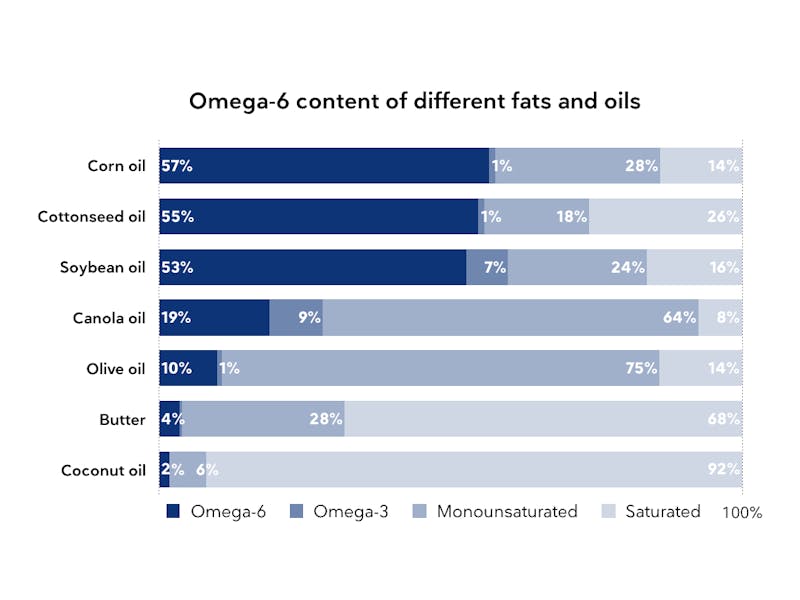

Most vegetable oils contain predominantly omega-6 fatty acids and contribute to the abundance of omega-6 fatty acids (over omega-3 fatty acids) in the standard American diet.14

This is a decidedly modern pattern. Until relatively recently, it’s estimated that humans consumed omega-6 and omega-3 fats in a roughly 1:1 ratio. Today, that ratio is estimated to be around 16:1, on average.15

For more on the origin and structure of different types of fat, check out our guide below:

Healthy fats on a keto or low-carb diet

Are vegetable oils healthy?

Whether vegetable oils are beneficial or harmful is a topic of intense debate. Let’s take a look at the potential concerns about them.

What happens to the vegetable oils that we eat?

Fatty acids can be burned for energy, so vegetable oils are a source of fuel. If we do not need that energy immediately, our bodies store it in our fat cells.

But fatty acids are also used to build and repair body parts, create internal signaling molecules, and build cell membranes. And the selection of fatty acids in the food you eat provides the array of building blocks available to the body.16 So the vegetable oils you eat literally become a part of you. Your mother was right — you really are what you eat!

The fatty acids vegetable oils provide are not identical to those found in more traditional fats. Some evidence, albeit weak evidence, suggests the fatty acids from vegetable oils may be less stable than those from more traditional fats. Therefore, incorporating them into our cell membranes could potentially negatively affect membrane fluidity and cellular function.17

On the other hand, other data in humans show that the omega-6 fatty acid phospholipid content (a marker for omega-6 consumption) is positively related to insulin sensitivity.18

How can we make sense of this contradictory data? Read on for more details, including data from controlled trials, which are the highest-quality evidence.

Are vegetable oils inflammatory?

There are theories and mechanistic studies suggesting that a high absolute intake of omega-6 fatty acids and a high ratio of omega-6 to omega-3 fatty acids can increase inflammation.19 Despite a number of suggestive mechanistic studies, when repeatedly tested in randomized trials, this hasn’t been shown to be true.20

For example, one systematic review found no evidence that linoleic acid, the main omega-6 fatty acid in vegetable oils, increases inflammatory markers, at least in healthy people.21 Similarly, a meta-analysis of RCTs found no effect of omega-6 fatty acids on inflammatory markers in patients with inflammatory bowel disease.22

Looking at a couple of representative randomized controlled trials — one in people with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and one in overweight men — it was found that meals high in omega-6 fatty acids led to lower levels of inflammatory markers than meals high in saturated fat. Of note, both groups consumed 40% of their calories from carbohydrates.23

Bottom line: There’s no clear high-quality human evidence that vegetable oils are inflammatory, despite the many mechanistic studies suggesting they are.

What happens when we cook with vegetable oils?

Vegetable oils contain mostly polyunsaturated and monounsaturated fatty acids, which means they are liquid at room temperature. It also means they are typically less stable than predominantly saturated fats. This is because unsaturated fatty acids have one or more double chemical bonds that react with oxygen more easily than do the single bonds in a saturated fatty acid.

Even if vegetable oils can be stabilized during production to achieve a reasonable shelf life, adding heat can oxidize (damage) them.24

Some animal studies have shown that consuming repeatedly heated vegetable oils may increase blood pressure and cause other adverse health effects due to the formation of aldehydes and other potentially toxic compounds.25

There is limited short-term evidence that long-term heating (8 hours at 210 degrees Celsius) of polyunsaturated fats like safflower oil may increase oxidation of fatty acids in humans, when compared to heating olive oil.26 However, other studies show that despite this increased oxidation, there are no clear negative health consequences.27

At this time, research suggests that vegetable oils are probably safe for cooking as long as they aren’t exposed to very high temperatures for long time periods. However, the quality of the data is not strong and more research is needed, as questions still exist. 28

To minimize any risk, it could still be a good idea to mainly use more stable oils for cooking. Fats that contain higher levels of saturated fatty acids, like clarified butter and coconut oil, may be safer for cooking because they remain stable at high heat.29 These mostly saturated fats are solid at room temperature, do not become rancid when stored, and resist oxidation when heated.30

Lard and extra virgin olive oil, both made up of mostly monounsaturated fatty acids, are also quite heat stable.31 Monounsaturated fat-rich oils, such as cold pressed rapeseed oil, may also be stable at high heat possibly related to its beta-carotene and tocopherol content.32

Are vegetable oils “heart healthy”?

For decades public health officials have recommended that we replace butter and other saturated fats with vegetable oils for better heart health. But is there strong evidence that this reduces heart disease risk?

Observational studies are mixed but typically find that people who eat more polyunsaturated fat and less saturated fat have slightly fewer heart events.33

Observational data like this can’t prove that eating more PUFAs protects heart health, though; it only suggests a possible relationship between the two. This is because people who tend to eat more PUFAs may have a greater tendency for other healthy behaviors. In other words, the position that vegetable oils are superior and “heart healthy” is largely based on very weak observational associations.

If you’re interested in learning more about the problems with inferring causation from observational studies, have a look at our guide.

Before replacing butter and other natural fats with vegetable oils, we recommend looking for better evidence from carefully designed clinical trials!

Randomized clinical trials (RCTs) are considered the “gold standard” for evidence. And meta-analyses that pool the evidence from several RCTs provide the strongest, best quality of evidence.

At least five of these recent meta-analyses of RCTs find no link between vegetable oils and death due to heart disease.34

However, a few other recent meta-analyses suggest that vegetable oils might reduce heart disease risk, though the effect is fairly small.35

How can different meta-analyses come up with slightly different answers like this? It depends on many factors, such as: which clinical trials the authors of the review include, what other types of fat are included in the diet, the population in question, the length of follow-up of the studies, and many other factors.36

For example, some meta-analyses exclude large RCTs like the Minnesota Coronary Experiment and the Sydney Diet Heart Study. These studies found that diets higher in vegetable oils and lower in saturated fat did indeed lower total blood cholesterol. Yet the lower cholesterol level did not improve mortality rates.37

In fact, in these two trials, the opposite was true. The groups who consumed more vegetable oil actually had higher death rates, despite their lower blood cholesterol levels.

However, these trials also had some significant deficiencies. For example, in the Minnesota Coronary Experiment, they used lots of heavily processed foods that had other important dietary components like omega-3 fatty acids removed. In addition, the corn oil margarine which was used was created by hydrogenating the fat, which resulted in a high quantity of trans fat in the intervention group.

We now know that omega-3 fats are beneficial in the prevention of heart disease and that trans fats cause heart disease. So it’s possible that those confounding factors affected the study’s conclusions.

As we note in our saturated fat guide, it is very difficult for scientists to study the effect of nutrition on heart disease because heart disease develops over such a long period of time.

Long-term nutrition studies are especially challenging because you can never be sure that the people within the study are following the diet to which they were randomized.

However, in the case of omega-6 and -3 fatty acids, scientists have an advantage, because they can measure the fatty acid composition of the body’s own cells as a measure of intake.38 We can then use these so-called “biomarkers” as objective markers of intake in prospective cohort studies. This helps to overcome a significant limitation of epidemiological nutrition studies, which typically rely on self-reported data.

Studies that do this find a beneficial association between serum linoleic acid and reduced cardiovascular disease mortality.39 Notably, having sufficient omega-3 intake alongside that of omega-6 is a key point noted by expert groups.40

Nevertheless, any protective effect of vegetable oil or linoleic acid is not always consistent, and any effect observed in randomized controlled trials is generally weak.

It’s a bit confusing, isn’t it? The American Heart Association (AHA) bases its endorsements of vegetable oils on the purported link between lower LDL cholesterol levels and better heart health.41 But as shown, many of the clinical trials do not support that line of reasoning.

Do vegetable oils lower LDL cholesterol? Yes.42 Does that improve health outcomes that matter most to patients, i.e., does this prolong life, or save anyone from dying of heart disease? The answer from all these trials appears to be that the effect is either small or non-existent.

If vegetable oils are truly good for our heart health, why aren’t the RCTs more consistently showing that people who consume them consistently live longer lives?

Some scientists and doctors think that the unstable, easily oxidized PUFAs may play a role in the development of coronary heart disease.43Yet this also remains to be proven in high-quality experimental studies, and antioxidant therapies don’t appear to reduce the risk of CHD in randomized trials.44

What’s the bottom line? The science is still inconclusive. There is a lack of consistent evidence proving vegetable oils meaningfully improve heart health and all-cause mortality. Pragmatic advice for those concerned about vegetable oils for heart health can choose to consume whole, natural foods which contain linoleic acid alongside other healthy fats, such as nuts, seeds, oily fish, avocado and olive oil.

Do vegetable oils increase cancer risk?

As we struggle to understand cancer risk, diet is often identified as a key driver. But studies are all over the map. One observational trial (and the splashy headlines that follow) shows a particular food is protective; the next trial of the same food shows the opposite effect.45

As with coronary heart disease, cancer develops over long periods of time. Cancer is also arguably less well understood than heart disease. Many cancers are also rarer than heart disease, which makes studying these cancers more difficult, as you need a much larger sample size.

There are some observational studies showing associations between high omega-6 polyunsaturated fatty acid consumption and cancer.46 However, analyzing all observational studies together generally shows no or minimal link between the two.47

But remember, this is observational data, and we cannot assume causation from this weak evidence.

Ultimately, we must look to well-designed clinical trials for answers. There is little of this rigorous science available.

An older trial, conducted in a Los Angeles Veterans’ home in the late 60s, revealed increased cancer mortality among men eating the experimental diet that was heavy in vegetable oils.48 (This trial also showed lower CVD mortality for those replacing dairy fats with vegetable oils.)

But there were problems with the study, such as more heavy smokers in the control group, and subjects eating many meals away from the controlled institutional setting. We simply need more data to carefully evaluate vegetable oils and cancer risk.

Bottom line: We don’t yet know for sure if vegetable oils have any significant effect on cancer risk; the weak evidence we do have suggests minimal to zero impact.

Do vegetable oils affect mental health?

Some psychiatry experts have suggested that high omega-6 intake contributes to ADHD and depression.49 Psychiatrist Georgia Ede writes about this potential link and the mechanisms she believes are behind it, on her website.

However, until clinical trials are completed, we just don’t know whether or not vegetable oils have contributed to the escalating rates of anxiety, attention disorders, and depression in recent decades.

Are vegetable oils contributing to the obesity and diabetes epidemics?

The rise of obesity and diabetes that we have seen over the last 40 years has been matched by an equally dramatic increase in vegetable oil consumption. Is there a connection, or is this just a coincidence?

Animal studies are numerous and mixed. But in humans, the science is scant.

A Cochrane review of clinical trials concluded that consuming more polyunsaturated fats likely has little or no effect on body weight. Overall, researchers found that increasing polyunsaturated fat intake (omega-3, omega-6, or both) led to a slight but significant gain of 0.76 kilos (1.7 pounds), on average, over one to eight years.50

The question of a causal link between vegetable oils and diabetes has yet to be carefully explored. A recent systematic review of clinical trials found that high intake of either omega-6 or omega-3 fatty acids failed to improve blood sugar control or reduce diabetes risk.51

However, the majority of the trials looked at omega-3 supplementation, not omega-6s or vegetable oils. Long-term “food-based” trials are very difficult to carry out, as people typically revert to their normal intake over time. This is one of the reasons why most long-term trials fail to find any effect.

There are a number of shorter-term trials which do show benefit of replacing saturated fat with polyunsaturated fats on important markers for type 2 diabetes. For instance, in well-controlled feeding studies, replacing saturated fat with omega-6 polyunsaturated fat improves insulin sensitivity and lowers abdominal and liver fat.52

Omega-6-rich fats also appear to protect against fat storage in the liver during overfeeding. For example, overconsuming palm oil (saturated fat) but not sunflower oil (omega-6) has been shown to increase liver fat in lean and overweight individuals.53

Even in the context of a ketogenic diet, one five-day study showed that getting more fat from PUFAs at the expense of saturated fat increased ketosis and improved insulin sensitivity.54

Because these studies were of short duration, we don’t know whether the effects last over time. And while many of these studies suggest that consuming omega-6 fats in place of saturated fats may be beneficial, the actual improvement is very small.

So how do you navigate all this uncertainty? See our conclusion below.

Our top sauce and dressing recipes

Conclusion

At this point there’s still quite a bit we don’t know about vegetable oils. Consuming small amounts of vegetable oils might make sense for some of us, depending on lifestyle, food preferences, and other factors.

However, if your goals include eating less processed food — as ours do — the best course may be to avoid these newcomers and return to traditional dietary fat sources. Get your fats from whole foods, including avocados, oily fish, nuts, seeds, olive oil, traditional oils, butter, coconut oil and meats.

Five step action plan: How to reduce vegetable oils in your diet

Here are five steps to help you reduce potentially excessive amounts of omega-6-rich vegetable oils in your diet.

- Stop buying vegetable oils. The most obvious step is easy — stop buying them! Substitute a different fat for frying, baking and dressing. Try one of these: butter (or ghee), sour cream, lard, tallow, schmaltz, extra-virgin olive oil, cold-pressed coconut oil, and extra-virgin red palm oils. Why not check out our delicious guide dedicated to eating more healthy fat!

- Limit your vegetable oil intake to mayonnaise and salad dressing. Some of us (or our family members) just don’t love — or have the time to prepare — homemade mayo and salad dressings. If you drizzle olive oil on vegetables and cook with butter or other heat-stable fats, using packaged salad dressing or mayo made with vegetable oil is probably okay. If you’d rather avoid vegetable oils completely (a choice we completely understand), try our quick and easy salad dressing (see our recipes in the section above, too) and homemade mayo!

- Substitute with quality oils when eating out. When you eat out, ask for olive oil and vinegar for your salad. (Some people even like to pack their own favorite dressing.) Another trick at restaurants is asking the waiter if the chef can fry your food in butter or coconut oil instead of the standard cooking oil. Not all establishments can accommodate this request, but it’s worth a try!

- Cut out baked goods and snacks. There are lots of reasons (hello, sugar and refined grains) to avoid commercial baked goods and snacks, and now you have one more reason — they usually contain vegetable oils. Most bakery-made or packaged cookies, pastries, cakes, breads, crackers, chips and bars are made with vegetable oils. Check out the ingredients list before you buy.

- If you have to use vegetable oil, choose high-oleic varieties. A potential downside of vegetable oils is their high omega-6 fatty acid content. However, high-oleic-versions of safflower, sunflower, and canola oils are at least 70% monounsaturated fat and only 10-15% omega-6 fat, making them more shelf-stable and suitable for high-heat cooking.55

Are you still confused about vegetable oils? Science definitely doesn’t have all the answers. Our advice? When in doubt, stick with foods that have been around for thousands of years.

Author info

This guide was originally written by Jennifer Calihan and published in December 2018. It was thoroughly updated by Franziska Spritzler, RD, in September 2019. Medical review by Dr. Bret Scher, MD, Dr. Michael Tamber, and Dr. Nicola Guess.

Did you enjoy this guide?

We hope so. We want to take this opportunity to mention that Diet Doctor takes no money from ads, industry or product sales. Our revenues come solely from members who want to support our purpose of empowering people everywhere to dramatically improve their health.

Will you consider joining us as a member as we pursue our mission to make low carb simple?

Vegetable oils: Are they healthy? - the evidence

This guide is written by Franziska Spritzler, RD and was last updated on June 19, 2025. It was medically reviewed by Nicola Guess, RD MPH PhD on June 7, 2021 and Dr. Bret Scher, MD on June 21, 2022.

The guide contains scientific references. You can find these in the notes throughout the text, and click the links to read the peer-reviewed scientific papers. When appropriate we include a grading of the strength of the evidence, with a link to our policy on this. Our evidence-based guides are updated at least once per year to reflect and reference the latest science on the topic.

All our evidence-based health guides are written or reviewed by medical doctors who are experts on the topic. To stay unbiased we show no ads, sell no physical products, and take no money from the industry. We're fully funded by the people, via an optional membership. Most information at Diet Doctor is free forever.

Read more about our policies and work with evidence-based guides, nutritional controversies, our editorial team, and our medical review board.

Should you find any inaccuracy in this guide, please email andreas@dietdoctor.com.

AOCS Press 1998: Fats and oils handbook, chapter 5: the extraction of vegetable oils [textbook chapter; ungraded]

↩Consuming trans fats has been shown to raise LDL cholesterol, lower HDL cholesterol, and increase inflammatory markers:

The New England Journal of Medicine 1990: Effect of dietary trans fatty acids on high-density and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels in healthy subjects [randomized trial; moderate evidence]

Lipids 2010: Effects of partially hydrogenated, semi-saturated, and high oleate vegetable oils on inflammatory markers and lipids [randomized trial; moderate evidence]

This meta-analysis of observational trials showed an association between trans fats and mortality, as well as heart disease:

British Medical Journal 2015: Intake of saturated and trans unsaturated fatty acids and risk of all cause mortality, cardiovascular disease, and type 2 diabetes: systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies[meta-analysis of observational studies; very weak evidence] ↩

Canola, sunflower, and some other vegetable oils can also be pressed and are referred to as “cold pressed” or “expeller pressed” oils. After pressing, most undergo processing similar to solvent-extracted oils. ↩

Chemical Engineering Transactions 2017: Recovery of vegetable oil from spent bleaching earth: state of-the-art and prospect for process intensification [overview article; ungraded] ↩

World Review of Nutrition & Dietetics 1998: Dietary intake of long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids during the paleolithic [overview article; ungraded] ↩

American Society for Horticultural Science 2007: Olive oil: history, production, and characteristics of the world’s classic oils [overview article] ↩

Vegetable Oils and Oilseeds 1970: A review of production, trade, utilisation and prices relating to groundnuts, cottonseed, linseed, soya beans, coconut and oil palm products, olive oil and other oilseeds and oils [text book article; ungraded] ↩

Journal of the American Oil Chemists Society 1974: Fat in today’s food supply – level of use and sources [overview article; ungraded]

The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2005: Origins and evolution of the Western diet: health implications for the 21st century [overview article; ungraded] ↩

American Journal os Clinical Nutrition 2011: Changes in consumption of omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids in the United States during the 20th century [observational study, weak evidence] ↩

Prostaglandins Leukotrienes and Essential Fatty Acids 2018: Trends in linoleic acid intake in the United States adult population: NHANES 1999-2014 [observational study, weak evidence] ↩

Advances in Nutrition 2015: Increase in adipose tissue linoleic acid of US Adults in the last half century [observational study, weak evidence] ↩

There are exceptions. For instance, high-oleic versions of canola, safflower, and sunflower oil are at least 70% monounsaturated fat. However, these are much less commonly consumed than the higher omega-6 oils. ↩

Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2006: Evolutionary aspects of diet, the omega-6/omega-3 ratio and genetic variation: nutritional implications for chronic diseases [overview article; ungraded] ↩Biologic Reviews of the Cambridge Philosophical Society 2005: Dietary fats and membrane function: implications for metabolism and disease [overview article; ungraded] ↩

Metabolism 1989: Dietary fat and hormonal effects on erythrocyte membrane fluidity and lipid composition in adult women [non-controlled study; weak evidence]

Biochimica et Biophysica Acta 2014: The effect of natural and synthetic fatty acids on membrane structure, microdomain organization, cellular functions and human health [overview article; ungraded] ↩

European Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2011: Relationship between red cell membrane fatty acids and adipokines in individuals with varying insulin sensitivity [observational study; weak evidence] ↩

Journal of Nutrition and Metabolism 2012: Health implications of high dietary omega-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids [overview article; ungraded] ↩

At Diet Doctor, we believe that results of mechanistic studies, without validation by human outcome trials, represent a very low level of evidence – one that shouldn’t automatically be used as the basis for clinical decisions. Mechanistic studies should, however, serve as guidance for future trials to test hypotheses regarding potential effects of these mechanisms on human outcomes. Human physiology is a complex array of interconnected systems. Therefore, we often find that a simple mechanistic hypothesis may or may not translate to significant health considerations. ↩

Journal of the Academy of Nutrition & Dietetics 2012: Effect of dietary linoleic acid on markers of inflammation in healthy persons: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials [strong evidence] ↩

European Journal of Nutrition 2020: Long-term effects of increasing omega-3, omega-6 and total polyunsaturated fats on inflammatory bowel disease and markers of inflammation: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials [systematic review of randomized trials; strong evidence] ↩

The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2012: Effects of n-6 PUFAs compared with SFAs on liver fat, lipoproteins, and inflammation in abdominal obesity: a randomized controlled trial [moderate evidence]

The Journal of Nutrition 2011: Exchanging saturated fatty acids for (n-6) polyunsaturated fatty acids in a mixed meal may decrease postprandial lipemia and markers of inflammation and endothelial activity in overweight me [randomized trial; moderate evidence] ↩

Heating polyunsaturated fats to high temperatures makes them more likely to react with oxygen, leading to the formation of potentially harmful byproducts:

Food and Nutrition Research 2011: Determination of lipid oxidation products in vegetable oils and marine omega-3 supplements [mechanistic study; ungraded]

Journal of the American Oil Chemists’ Society 2002: Formation of 4-hydroxynonenal, a toxic aldehyde, in soybean oil at frying temperature [mechanistic study; ungraded]

↩Pakistan Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 2016: Changes in blood pressure, vascular reactivity and inflammatory biomarkers following consumption of heated corn oil [rat study; very weak evidence]

Clinics 2011: The effects of heated vegetable oils on blood pressure in rats [rat study; very weak evidence]

Toxicology Reports 2016: Evaluation of the deleterious health effects of consumption of repeatedly heated vegetable oil [rat study; very weak evidence] ↩

Atherosclerosis 2002: Effect of meals rich in heated olive and safflower oils on oxidation of postprandial serum in healthy men [randomized trial; moderate evidence]

European Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2001: The effect of meals rich in thermally stressed olive and safflower oils on postprandial serum paraoxonase activity in patients with diabetes [randomized trial; moderate evidence]

↩Nutrition, Metabolism, and Cardiovascular Disease 2001: Normal endothelial function after meals rich in olive or safflower oil previously used for deep frying [non-randomized study, weak evidence]

British Journal of Nutrition 2015: Does cooking with vegetable oils increase the risk of chronic diseases?: A Systematic Review [review of observational studies, weak evidence]

↩British Journal of Nutrition 2015: Possible adverse effects of frying with vegetable oils [overview article; ungraded] ↩

Journal of Foodservice 2006: Health effects of oxidized heated oils [overview article; ungraded] ↩

Indian Journal of Clinical Biochemistry 2000: Lipid peroxidation in culinary oils subjected to thermal stress [mechanistic study; ungraded] ↩

Czech Journal of Food Sciences 2005: Oxidative changes of vegetable oils during microwave heating [mechanistic study; ungraded]

Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry: How heating affects extra virgin olive oil quality indexes and chemical composition [mechanistic study; ungraded] ↩

Chemical Monthly 2017: Thermal degradation assessment of canola and olive oil using ultra-fast gas chromatography coupled with chemometrics [non-randomized study, weak evidence]

Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety 2006: Mechanisms and factors for edible oil oxidation [overview article; ungraded]

↩American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2020: Dietary intake and biomarkers of linoleic acid and mortality: systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies [meta-analysis of observational studies with low RR, weak evidence]

Circulation 2014: Dietary linoleic acid and risk of coronary heart disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies [meta-analysis of observational studies; weak evidence]

The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2009: Major types of dietary fat and risk of coronary heart disease: a pooled analysis of 11 cohort studies [Pooled analysis of observational studies; weak evidence]

Circulation 2014: Circulating omega-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids and total and cause-specific mortality [meat-analysis of observation studies; weak evidence]

JAMA Internal Medicine 2016: Association of specific dietary fats with total and cause-specific mortality [observational study; weak evidence] ↩

These five meta-analyses find no link between vegetable oils and cardiovascular mortality:

The British Journal of Nutrition 2010: n-6 fatty acid-specific and mixed polyunsaturate dietary interventions have different effects on CHD risk: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. [strong evidence]

Hamley Nutrition Journal 2017: The effect of replacing saturated fat with mostly n-6 polyunsaturated fat on coronary heart disease: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials [strong evidence]

BMJ 2016: Re-evaluation of the traditional diet-heart hypothesis: analysis of recovered data from Minnesota Coronary Experiment (1968-73) [strong evidence]

Annals of Internal Medicine 2014: Association of dietary, circulating, and supplement fatty acids with coronary risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis [strong evidence]

BMJ 2016: Evidence from randomised controlled trials does not support current dietary fat guidelines: a systematic review and meta-analysis [strong evidence] ↩

Typically, meta-analyses are strong evidence; however, meta-analyses on this issue do not all agree, and the noted effects are modest.

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2018: Polyunsaturated fatty acids for prevention and treatment of diseases of the heart and circulation [strong evidence]

PLOS Medicine 2010: Effects on coronary heart disease of increasing polyunsaturated fat in place of saturated fat: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials [strong evidence] ↩

Circulation 2009: Omega-6 Fatty Acids and Risk for Cardiovascular Disease: A Science Advisory From the American Heart Association Nutrition Subcommittee of the Council on Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Metabolism; Council on Cardiovascular Nursing; And Council on Epidemiology and Prevention [overview article; ungraded] ↩

These recovered randomized clinical trials are presented in detail, and in addition, each one includes an updated meta-analysis:

BMJ 2016: Re-evaluation of the traditional diet-heart hypothesis: analysis of recovered data from Minnesota Coronary Experiment (1968-73) [strong evidence]

BMJ 2013: Use of dietary linoleic acid for secondary prevention of coronary heart disease and death: evaluation of recovered data from the Sydney Diet Heart Study and updated meta-analysis [strong evidence]

↩Advances in Nutrition 2015: Increase in adipose tissue linoleic acid of US Adults in the last half century [observational study, weak evidence] ↩

Archives of Internal Medicine 2005: Prediction of cardiovascular mortality in middle-aged men by dietary and serum linoleic and polyunsaturated fatty acids [observational study; weak evidence] ↩

Circulation 2009: Omega-6 Fatty Acids and Risk for Cardiovascular Disease: A Science Advisory From the American Heart Association Nutrition Subcommittee of the Council on Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Metabolism; Council on Cardiovascular Nursing; And Council on Epidemiology and Prevention [overview article; ungraded] ↩

From the AHA website: “Polyunsaturated fats can help reduce bad cholesterol levels in your blood, which can lower your risk of heart disease and stroke.” ↩

Although the Minnesota Coronary Experiment and Sydney Diet Heart Study measured total cholesterol rather than LDL cholesterol, more recent studies show that LDL-C is indeed lowered by diets high in polyunsaturated fat:

Journal of the American Heart Association 2019: Replacing saturated fat with walnuts or vegetable oils improves central blood pressure and serum lipids in adults at risk for cardiovascular disease: a randomized controlled‐feeding trial [moderate evidence]

American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2015: Replacement of saturated with unsaturated fats had no impact on vascular function but beneficial effects on lipid biomarkers, E-selectin, and blood pressure: results from the randomized, controlled Dietary Intervention and VAScular function (DIVAS) study [randomized trial; moderate evidence]

International Journal of Food Sciences and Nutrition 2009: Small, qualitative changes in fatty acid intake decrease plasma low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol levels in mildly hypercholesterolemic outpatients on their usual high-fat diets [randomized trial; moderate evidence] ↩

This includes James DiNicolantonio, PhD, and James O’Keefe, MD, who recently published a paper linking vegetable oils high in omega-6 fat to heart disease:

Open Heart 2018: Omega-6 vegetable oils as a driver of coronary heart disease: the oxidized linoleic acid hypothesis [overview article; ungraded] ↩

American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2006: Vitamin-mineral supplementation and the progression of atherosclerosis: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials [systematic review of randomized trials; strong evidence]

Circulation 2009: Omega-6 fatty acids and risk for cardiovascular disease: A science advisory from the American Heart Association nutrition subcommittee of the Council on Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Metabolism; Council on Cardiovascular Nursing; and Council on Epidemiology and Prevention [overview article; ungraded] ↩

A review of studies investigating 50 common ingredients concluded that almost every food was linked to both positive and negative health effects, including coffee, wine, eggs, and beef:

The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2013: Is everything we eat associated with cancer? A systematic cookbook review [systematic review of observational studies; very weak evidence] ↩

The International Journal of Cancer 2011: Opposing effects of dietary n-3 and n-6 fatty acids on mammary carcinogenesis [observational study; weak evidence]

British Journal of Cancer 2003: The Singapore Chinese Health Study [observational study; weak evidence]

BMC Medicine 2012: New insights into the health effects of dietary saturated and omega-6 and omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids [overview article; ungraded] ↩

American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2020: Dietary intake and biomarkers of linoleic acid and mortality: systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies [meta-analysis of observational studies with low RR, weak evidence]

Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention 2015: Vegetable oil intake and breast cancer risk: a meta-analysis [meta analysis of observational studies; weak evidence]

Prostate Cancer 2012: Relationship of dietary intake of omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids with risk of prostate cancer development: a meta-analysis of prospective studies and review of literature [meta analysis of observational studies; weak evidence]

↩Circulation 1969: A controlled clinical trial of a diet high in unsaturated fat in preventing complications of atherosclerosis [moderate evidence] ↩

Psychosomatic Medicine 2007: Depressive symptoms, omega-6:omega-3 fatty acids, and inflammation in older adults [observational study; very weak evidence]

Translational Psychiatry 2017: Omega-6 to omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid ratio and subsequent mood disorders in young people with at-risk mental states: a 7-year longitudinal study [observational study; very weak evidence]

↩Importantly, this meta-analysis included trials in which people increased their consumption of polyunsaturated fats from a variety of sources. Some study participants were instructed to eat more walnuts, and several of the trials looked at the effects of boosting omega-3 fat intake via consuming fish oil or flax supplements. So the effects of vegetable oils per se on weight could be somewhat different:

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2018: Polyunsaturated fatty acids for prevention and treatment of diseases of the heart and circulation [systematic review of randomized trials; strong evidence]

↩British Medical Journal 2019: Omega-3, omega-6, and total dietary polyunsaturated fat for prevention and treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials [strong evidence] ↩

Of note, these were not studied in the context of a low-carb diet:

American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2012: Effects of n-6 PUFAs compared with SFAs on liver fat, lipoproteins, and inflammation in abdominal obesity: A randomized controlled trial [moderate evidence]

Diabetologia 2002: Substituting dietary saturated fat with polyunsaturated fat changes abdominal fat distribution and improves insulin sensitivity [randomized trial; moderate evidence]

↩Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 2019: Overeating saturated fat promotes fatty liver and ceramides compared with polyunsaturated fat: A randomized trial [moderate evidence]

Diabetes 2014:

Overfeeding polyunsaturated and saturated fat causes distinct effects on liver and visceral fat accumulation in humans [randomized trial; moderate evidence]

↩Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 2004: Differential metabolic effects of saturated versus polyunsaturated fats in ketogenic diets [randomized trial; moderate evidence] ↩

Journal of the American Oil Chemists Society 1967: High-oleic safflower oil. Stability and chemical modification [overview article; ungraded]

Food Chemistry 2013: Frying stability of high oleic sunflower oils as affected by composition of tocopherol isomers and linoleic acid content [mechanistic study; ungraded]

Journal of the American Oil Chemists Society 2013: Performance of regular and modified canola and soybean oils in rotational frying [mechanistic study; ungraded] ↩