‘What the Health’ review: Health claims backed by no solid evidence

Is eating meat killing you? That’s what you may think after watching the popular new movie “What the Health” (WTH) on Netflix.

WTH portrays itself as a documentary by film maker Kip Anderson, who sets out in his trusty blue van from San Francisco to answer questions about a healthy diet. Since Anderson is already a vegan whose previous movie, Cowspiracy, argued that cows drive the destruction of the planet, we’re pretty sure where he’s going to end up.

Sure enough, despite his effort to appear shocked and surprised at his “discoveries” along the way, he concludes that not only is a plant-based diet best for health, but also that animal foods cause death and disease to all people who eat them.

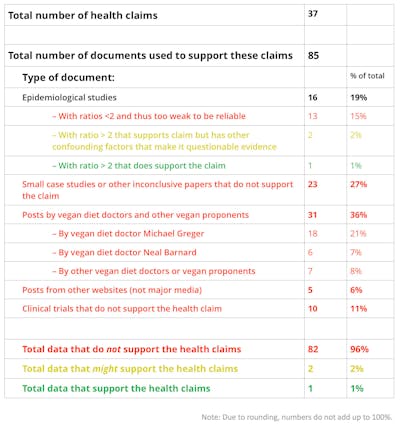

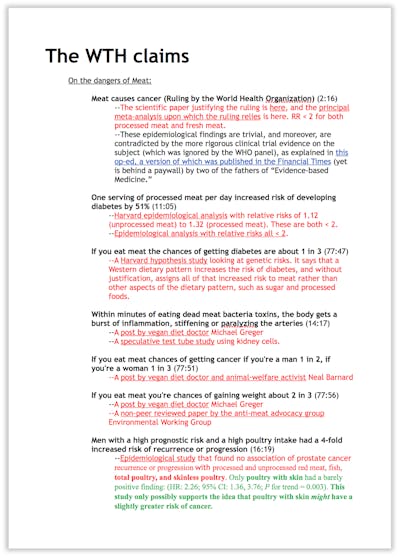

The film makes 37 health claims, and for this review, I investigated every single one. (WTH also makes a myriad of claims about contaminants and issues of environmental impact, but these are outside my field of expertise, so I looked only at the claims on health.)

A few notes

Before diving into these claims, however, I’m going to make a few comments on the film’s tactics, go over a housekeeping point, and do a quick background primer on the science.

First, I’m no expert in movies, but this looks an awful lot like a horror flick to me, with scenes of Anderson driving ominously through shadowy tunnels or all alone in an unlit room, googling mysteries on his computer. Interviews are lit seemingly from a single bulb, as if talking to a mafia informant, and ominous music pulses in the background, creating an omniscient feeling of dread.

Scary videos of pregnant women (the most vulnerable!) with needles poking into their bellies are intermingled with revolting images of fatty, pulsating bodily tissues pierced by scalpels or incised by surgical devices. We see animations of a happily pregnant mother or innocent child drinking milk aglow in neon orange to signify its hidden dangers and then see that neon color suffuse their unaware bodies — if they only knew! “Choose your poison,” says one of the film’s experts, referring to the various ways that animal foods kill. “It’s a question of whether you want to be shot or hung.”

According to Anderson, the reason that we don’t know about these dangers is that the meat, dairy and egg industries are like “Big Tobacco,” the ultimate bad corporate actor that famously used underhanded tactics to cover up the dangers of a harmful product. Casting the animal-food industries in this role has been a successful tactic employed by vegetarian groups ever since the 1970s, but WTH takes this effort into hyper-drive.

The film also suggests our health problems are in part due to the excessive influence of Big Food and Big Pharma on our trusted public health institutions, such as the American Diabetes Association and American Heart Association (AHA). Here, I agree, although the film should have fleshed out the picture: WTH cites funding only from meat and dairy companies when in fact the full range of food industries are in on this game.1

Such donations make it hard for these associations to recommend healthy diets (e.g., the AHA puts its “healthy check mark” on sugar-laden cereals) or even advise people to choose better nutrition over drugs and medical devices. I’m also pleased to agree with another WTH point, made repeatedly throughout the film (in the scariest possible way), namely that these diseases take a huge toll on the health and wealth of our nations. Indeed they do.

Now, the housekeeping point. I come to this film with an obvious bias, since I’ve written a book, The Big Fat Surprise: Why Butter, Meat, and Cheese Belong in a Healthy Diet. The book’s central argument is that saturated fats and cholesterol have been unfairly maligned and are not, after all, bad for health.

Therefore, I don’t buy the film’s idea that animal foods are unhealthful based on these reasons (For a complete run-down on these arguments, read my book or for a brief overview, this recent piece in Medscape or this piece I wrote in the Wall Street Journal). Still, the film presents other arguments against animal foods, and I’m open to these.

Finally, a note on science. WTH, on its website, provides many links to data for its claims, so I’ve come up with a grading system. WTH cites the following types of evidence:

Epidemiology

Most of the claims in the film come from epidemiological studies. These are fundamentally limited in that they can only show associations and cannot establish causation. Therefore, this data is really meant only to generate hypotheses and can only rarely ‘prove’ them.2 Among the many problems with epidemiological studies are:

- The extreme unreliability of “food frequency questionnaires,” which depend upon people accurately remembering what they ate over the last 6 or 12 months.3

- The impossibility of fully adjusting for confounding variables. For instance, how does one adjust for the fact that heavy red-meat eaters are obviously people who’ve ignored their doctors’ orders about meat (since nearly all doctors now advise patients to cut down on red meat), and thus, these people are also probably ignoring “healthy living” advice in many other ways. They probably smoke more and fail to visit the doctor regularly or attend cultural events—all factors linked to poorer health outcomes and none of which epidemiologists can ever properly measure or adjust for.4 Moreover, researchers don’t actually know to what extent various foods like sugar or high-fructose corn-syrup cause disease, so they cannot even begin to adjust for those; And that is just the beginning of the discussion on problems in confounding.

- Epidemiologists cross-calculate hundreds of food and lifestyle variables against death rates from different ailments, resulting a huge number of associations. Just as a matter of probability, some of the positive results will be spurious. Statistical adjustments can be made to avoid this problem, but the Harvard epidemiologists, whose papers are principally cited by WTH, rarely make such adjustments.5

Thus, for all these reasons and more, scientists in most fields (except nutrition) agree that small associations—with “risk ratios” of less than 2 — are not reliable.6

Epidemiological studies with ratios <2 will therefore be coded in red.

(Note that a risk ratio is completely separate from those scary “relative change” numbers that articles report. An article might say: “meat increases the chances of breast cancer 68%!” Yet this number is exaggerated and often meaningless, as explained here.)

Clinical trials

This is a more rigorous kind of evidence that can show cause and effect.7 I will grade trials roughly according to the following criteria: Was it randomized? Did it have a control group? Was it sizeable? Was it on a relevant population? Did enough people finish the trial to make it meaningful? Do its results support the claim?

Clinical trials that fail to meet most of these standards will be coded in red.

Clinical trials that might support the claim will be coded in green.

Non-conclusive evidence

These include either studies that do not support the claim or evidence that is highly preliminary, such as papers speculating on possible hypotheses, case studies on 1-2 people, or test-tube studies on cell cultures. These represent the most preliminary types of research and cannot be considered conclusive evidence. All these non-conclusive studies will be coded in red.

Newspaper, magazine articles, and blog posts

Because these are not peer reviewed, they can’t be considered as rigorous sources of evidence, although some publications are better than others. Articles by biased sources (e.g., vegan diet doctors) will be coded in red, because they have both commercial and intellectual conflicts of interest. Mainstream media outlets that fact check their articles are more reliable, though still not a source of peer reviewed science, so they will be coded in yellow.

To review:

- Items in red cannot be considered support for the claim.

- Items in yellow are weak support for the claim.

- Items in green support the claim.

And… drumroll… here’s the evidence:8

In sum, 96% of the data do not support the claims made in this film. The film does not cite a single rigorous randomized controlled trial on humans supporting its arguments. Instead WTH presents a great deal of weak epidemiological data, case studies on one or two people, or other inconclusive evidence. Some of the studies cited actually conclude the opposite of what is claimed.

Moreover, the majority of “papers” turn out to be posts by vegan diet doctors — mainly Michael Greger and Neal Barnard. Both of these men are passionate animal welfare activists,9 so one can never know if they are seeking truth about a healthy diet or have started from the premise that they’d like to end all domestication of animals and proceed to cherry pick the science back from there.

Given the weak-to-non existent data presented in the film, the latter seems to be a pretty good possibility. In fact, WTH, based on zero sound science, is quite likely a piece of animal-welfare advocacy masquerading as a public health film.

For a comprehensive list of every WTH health claim, and the exact support, see this PDF document.

In conclusion

The film’s defenders might say that better studies are buried in all those posts by vegan diet doctors, but any researcher knows to cite primary sources rather than secondary ones. Where’s the science? It appears not to exist.

And we can assume that if the science has been so distorted and misrepresented for the claims on health, probably the same has been done for claims on other issues, on environmental impact, toxins, antibiotics, hormones, the evolution of humans, etc.

If this is the best evidence that a vegan diet can promote good health, then I’m not convinced. I’m more skeptical, even, based on a few solid observations:

- No human population in the history of civilization has ever been recorded surviving on a vegan diet.

- The vegan diet is nutritionally insufficient, lacking not only vitamin B12 but deficient in heme iron and folate (meaning that we should refer to it always as a “vegan diet plus supplements”).

- A near-vegan diet, in rigorous clinical trials, invariably causes HDL-cholesterol to drop and sometimes raises triglycerides, which are both signs of worsening heart attack risk; Over the last 30 years, as rates of obesity and diabetes have risen sharply in the U.S., the consumption of animal foods has declined steeply: whole milk is down 79%; red meat by 28% and beef by 35%; eggs are down by 13% and animal fats are down by 27%.10 Meanwhile, consumption of fruits is up by 35% and vegetables by 20%. All trends therefore point towards Americans shifting from an animal-based diet to a plant-based one, and this data contradict the idea that a continued shift towards plant-based foods will promote health.

- There’s the entire Indian subcontinent, where beef is not eaten by the large majority of people, which has seen diabetes explode over the past decade.

It’s also false that WTH is the movie that “health organizations don’t’ want you to see!” as it claims, since the president of the American College of Cardiology, interviewed in the film, expresses adamant support of the vegan diet, and the expert committee for the U.S. Dietary Guidelines in 2015 proposed eliminating meat from the list of “healthy foods.”

Thus, these two major public health institutions would presumably be happy for you to see this film. In fact, the plant-based diet has proponents in many high places, including the Harvard Chan School of Public Health, which produces many of the weak epidemiological associations cited in the movie. Claiming to be a Michael-Moore style underdog therefore appears merely to be one of the film’s rhetorical tricks.

Finally: I’d like to comment on this film as act of journalism. In WTH, Anderson’s role as a ‘reporter’ fails to meet any normal standards of the field. Not only does he hop a barbed-wire fence in what appears to be an act of illegal trespassing onto a hog farm in North Carolina, he also conducts a series of interviews that just made me laugh.

Zounds! “Yet again… more questions no one can answer,” intones Anderson. Yep, because these people have been hired to be operators and security guards, Mr. Anderson, not scientific experts. In the film, Anderson portrays these encounters as a series of “gotchya” moments in which he’s being stonewalled, but really, it’s nothing but illusion.

And that’s the whole film: scary images, compelling language, and the illusion of certainty and data, when in fact, there is none. Go ahead and eat your eggs, dairy and meat, folks, because there’s no sound evidence to show that these traditional, whole foods are bad for health.

Vegetarian low carb

While there may be no definite scientific health reason for everyone to go vegetarian or vegan, it can still certainly be a fine personal choice for many people.

Here at Diet Doctor we try to make low carb simple, and here are our top low-carb vegetarian recipes:

Why the fear of meat?

Where does the fear of meat come from originally? Learn more in our interview with Nina Teicholz:

Popular health movies

Nina Teicholz

Earlier

Low-Carb Vegetables – the Best and the Worst

How to Lose 130 Pounds on a Low-Carb Vegetarian Diet

New US Food Availability Data – Americans Follow the Guidelines & Get Obese

Equally, many industries benefit from the government’s “Check Off” programs. Pro-plant advocates like to cite the influence of the meat, dairy, and egg programs, but such programs also exist for soybean, wheat, avocados, potatoes, mushrooms, etc., all of which presumably have the same types of marketing efforts. WTH is again selecting presenting the evidence here. ↩

Epidemiological associations must be very strong to suggest causation.

The classic example is the association between smoking cigarettes and lung cancer, when the “relative risk” was very high: pack-a-day smokers had 10-to 35 times greater risk than non-smokers. Compare that to the 1.17 relative risk in cancer for the highest and lowest quintiles of red meat eaters. That number for processed red meat is 1.18. ↩

For more on this, see this paper by Edward Archer, Ph.D. or read this excellent piece by journalist Christie Aschwanden. I also cover this in my book, pp. 262-263. ↩

For more on this issue and how Walter Willett, a top Harvard epidemiologist, responded to accusations from statisticians on these issues, read my book, pp. 261-266. A recent post on Harvard and “p-hacking” is here. ↩

A similar measure of association, called a “hazards ratio,” is worth consideration if it is lower than .5 or larger than 2. If the hazard ratio is too close to 1, this means that the strength of association is nearly zero. ↩

The best trials are both randomized and controlled. In such trial, a researcher takes a group of subjects and randomly splits them into two equal groups. One gets a special diet while the other group receives a “control” diet. To be “well controlled,” each group must get the same intervention—i.e., the same amount of counseling, doctors’ visits, free food, and overall attention—in order to avoid the improvement that is inevitably seen in a patient just by virtue of receiving attention from a health professional. Because it turns out that most of us will watch what we eat a little more carefully if we know that someone is looking over our shoulder. ↩

Note: I’m not claiming that all these numbers are perfect. No doubt there is a mistake or two in here, as inevitably happens when reviewing a lot of data. Defenders of the vegan diet will likely use an error and dismiss the entire piece as “error ridden,” but whether I’ve counted every post correctly is dwarfed by the overwhelming amount of weak, biased and inconclusive data cited in WTH to make claims that are unjustifiable by any measure. ↩

Michael Greger “proudly serve[d] as the public health director for the Humane Society of the United States” until 2016, according to his website.

Neal Barnard has long been linked to animal-rights groups and activities, such as noted here, here, here, here, and here. ↩

Jeanine Bentley. U.S. Trends in Food Availability and a Dietary Assessment of Loss- Adjusted Food Availability, 1970-2014, EIB-166, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service, January 2017. ↩