High protein diet:

What it is and how to do it

You may have heard that high protein diets can help with weight loss and metabolic health. That’s why, at Diet Doctor, we feature high protein recipes and meal plans. But how do you know if a higher protein diet is right for you?

This guide will explain what high protein diets are, help you find the best high protein foods, and explore the potential benefits of high protein diets.

Key takeaways

What are the best high protein foods?Meat, seafood, eggs, beans, and dairy are all great sources of protein.

Find out if your favorite foods are also high protein.

What can high protein do for you?

You can lose weight, improve your health, and gain muscle by adding protein to your diet.

Learn more about how high protein could benefit you.

How much protein do I need?

More than you probably think! But it’s easy to add more protein to your diet with a few simple tricks.

Find them here.

1. What is a high protein diet?

A high protein diet is one where you work on getting plenty of protein — probably more than you are used to getting — as the first focus of your eating patterns. Protein-rich foods include eggs, meat, seafood, legumes, and dairy products. These foods are not only high in protein but high in nutrients in general. That means a high protein diet is also a high nutrition diet.

Increasing protein can be very helpful for weight loss because protein can help tame your appetite.

For people who want to build muscle, getting more protein than is typically recommended is a must. Current recommendations, known as the RDA or the recommended dietary allowance, are designed for “healthy people” and meant to prevent malnutrition; they aren’t meant to help increase muscle mass or improve medical conditions such as type 2 diabetes.

Diets with increased protein can have a positive effect on the treatment and prevention of type 2 diabetes and metabolic syndrome, and possibly even heart disease.

More high protein guides

More high protein guides

Learn what you need to get started with a high protein diet in this video:

You can read more about how much protein most people are eating now in our expanded section here:

2. What are the best high protein foods?

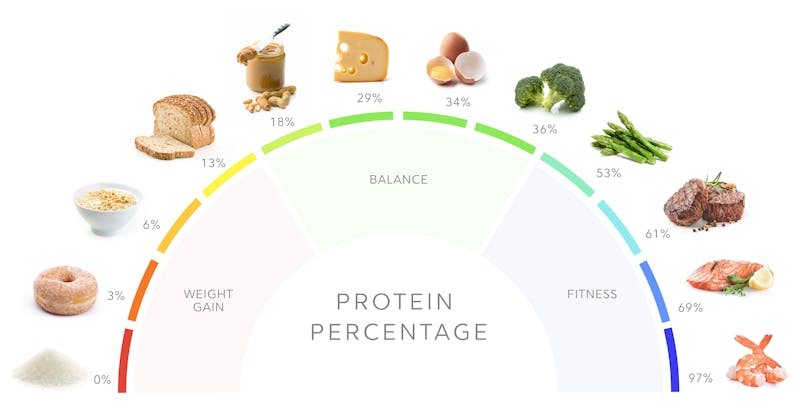

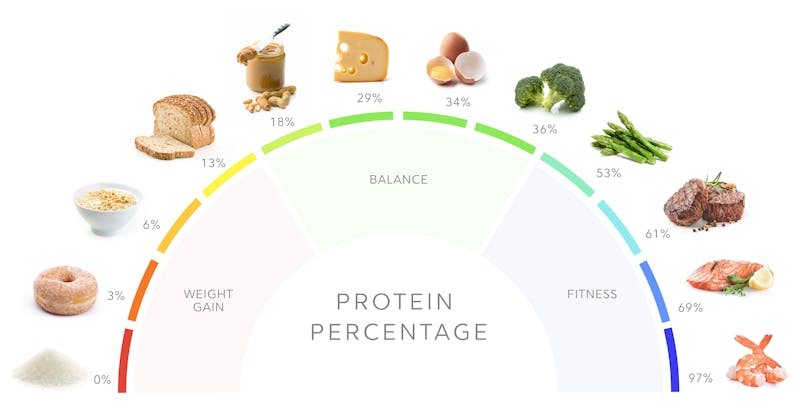

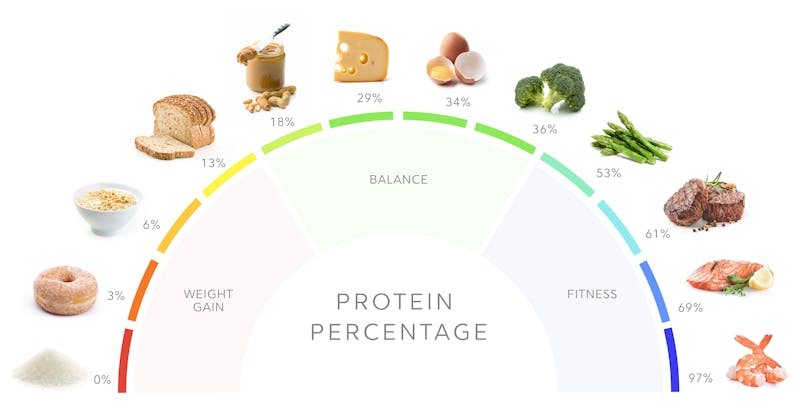

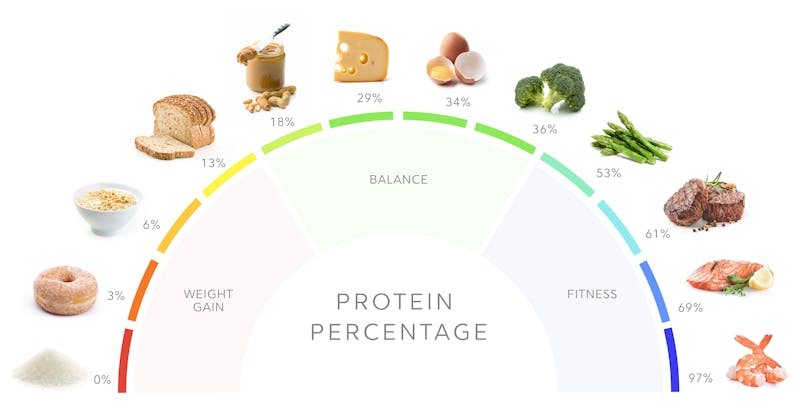

The best choices for high protein diets are foods with a high protein percentage. The protein percentage of a food tells you how much protein per calorie a food has.

Foods in the middle range of protein percentage can help you maintain your weight and your muscle mass. Going a little higher — over 30 or 35% — may help you lose weight.

Foods with a lower protein percentage may lead to weight gain, while foods with the highest protein percentage may be good choices for someone who is really trying to reduce body fat and become lean and fit.

Fortunately, most high protein foods are delicious and have plenty of vitamins and minerals, too. You can start with this list of the best high protein foods.

- Meat and poultry: beef, chicken, lamb, turkey

- Seafood: shrimp, crab, salmon, tuna

- Eggs: whole eggs or egg whites

- Dairy: cottage cheese, greek yogurt

- Legumes: Beans, lentils, peas, and soy

- Non-starchy vegetables: spinach, cauliflower, broccoli, mushrooms

If your diet consists mainly of the above foods, you are on your way to eating a healthy diet with plenty of protein.

Remember that non-starchy vegetables may have a high protein percentage, but they won’t give you the total protein, calories, or all the nutrients you need. Base your meals around a protein source — whether from animals or plants — and add high-protein-percentage vegetables for a little extra boost of amino acids, the building blocks of protein. Add just enough fat to make your meals delicious and filling. This approach will keep the total protein percentage of your meals high.

Here are a few tips to help you increase how much protein you eat and ensure you get adequate protein without adding too many unnecessary calories:

- Add extra egg whites to your scrambled eggs or omelets.

- Replace lower protein snacks, like nuts and cheese, with higher protein versions like lupini beans, zero-sugar jerky, or cold cuts.

- Include your favorite foods that are higher than 35% protein. Choose from the highest protein foods such as shrimp, chicken breasts, and lean cuts of meat.

- Swap higher fat cheese and yogurt with low-fat cheese or Greek yogurt. The lower-fat versions have higher protein percentages and therefore more protein per calorie.

You can find the protein percentage of many of your favorite foods and maybe discover a few new favorites, in our guide on the best high protein foods for weight loss.

What about protein powders?

Although our bias is that you should get most of your protein from whole foods, protein powders can still be part of a healthy, high protein diet.

You may not need protein powders if you prioritize the food on our list of best high protein foods. But if you fall short of your daily targets, protein powders are an easy and convenient way to get more protein.

Plus, protein powders are a great way to create high protein versions of your favorite desserts, low-carb bread, or smoothies.

If you are going to use protein powders, make sure they have few additives, such as sweeteners, maltodextrin, seed oils, or fillers.

Animal and plant protein powders are both good options, and you can choose which works best for your taste, preferences, and carbohydrate goals.

Summary

- Foods with the highest protein percentage are low in carbs and fat, like lean meat and seafood.

- To increase the protein in your diet, look for easy substitutions — snack on lupini beans or venison jerky, add two egg whites to your two whole eggs in the morning, or add more meat, seafood, dairy, or legumes to your meals.

- Mix protein foods with high-fiber vegetables – and don’t overdo fat – to create meals with a protein percentage above 35%.

- If you struggle to meet your protein goals with whole foods, consider protein powders.

3. High protein benefits

Weight loss

Multiple studies demonstrate higher protein intake helps with weight loss, specifically fat mass loss.

Metabolic benefits

Studies show diets higher in protein contribute to better blood sugar control and improved insulin sensitivity when compared to lower protein diets.

While protein may briefly increase insulin concentrations, high protein diets are not known to cause chronic hyperinsulinemia (high insulin levels). In fact, for people with prediabetes or type 2 diabetes, a higher protein diet may be more beneficial than a lower protein one.

Body composition

Higher protein diets promote lean muscle mass and encourage loss of fat mass.

Strength, bone health, and preventing frailty

As people age, muscle mass and bone health decline, which, if not corrected, can lead to physical frailty along with an increased risk of falls and bone fractures.

Satiety

Part of the reason for weight loss and better glycemic control could be protein’s ability to decrease hunger. Numerous studies show that as the protein amount increases, feelings of hunger and the amount of food eaten the rest of the day go down.

4. How do we define a high protein diet?

Summary: High protein diets are:

- Diets with more than 25% of calories from protein

- Over 1.6 grams of protein per kilo of body weight

- Diets with more protein than the Recommended Daily Allowance (RDA), which is set at 0.8 grams per kilo.

There is no universally agreed-upon definition of a high protein diet, and what you consider “high” may depend on where you start.

At Diet Doctor, we define adequate protein as over 1.2 grams per kilo per day and high protein as over 1.6 grams per kilo per day or above 25% of calories. We recommend that most people aim for 1.6 to 2 grams of protein per kilo or 25-35% of calories from protein to ensure adequate protein intake. And you should aim for the higher end of that range for a high protein diet.

Our definition of high protein is relative to The US Institute of Medicine, which sets 10% to 35% of calories as the acceptable range for protein intake. But it’s likely that you can safely eat much higher than 35% of your calories from protein.

5. How much protein do I need?

Summary

- Calculate your daily protein goal based on your height, activity level, and health goals.

- We recommend a protein intake of 1.6 to 2.0 grams per kilo of reference body weight.

- If you are very physically active or taller than 6 feet, consider staying at the higher end of this range.

- Distribute your protein intake throughout the day, with 30 to 40 grams per meal for women and 35 to 50 for men, if you are eating three meals a day.

The first step in eating a higher protein diet is setting your protein targets. We believe most people would benefit by increasing their protein intake to 1.6 to 2.0 grams per kilo per day, or 25 to 35% of daily calories. Use this simple chart to find out what your minimum daily protein target should be, based on your height.

Minimum daily protein target

| Height | Women | Men |

|---|---|---|

| Under 5’4″ ( < 163 cm) | 90 grams | 105 grams |

| 5’4″ to 5’7″ (163 to 170 cm) | 100 grams | 110 grams |

| 5’8″ to 5’10” (171 to 178 cm) | 110 grams | 120 grams |

| 5’11” to 6’2″ (179 to 188 cm) | 120 grams | 130 grams |

| Over 6’2″ (188 cm +) | 130 grams | 140 grams |

As the chart indicates, you should try to get around 100 grams if you’re a woman and 120 grams if you’re a man of average height and build. Eat more if you’re a man taller than 6 feet (183 cm) or a woman taller than 5’6″ (168 cm) or if you’re very physically active. Eat less if you’re shorter or have a very small frame.

If you are physically active, want to achieve very low body fat (less than 10% for men or 20% for women), or regularly practice intermittent fasting, you may want to add even more protein. Since there are no credible data showing harm from very high protein diets of over 2.0 grams per kilo of body weight per day — as we discuss later in this article — you can feel confident in adding more!

Read more about spacing your protein out during the day and whether you need to count calories.

6. Common concerns about high protein diets

According to some scientists and outdated published articles, high protein diets can be harmful to your kidneys, bones, and blood sugar. Some even believe that higher-protein diets lead to higher rates of cancer.

With respect to kidney health and protein intake, it is well-recognized that people with severe chronic kidney disease should restrict protein intake. Dietary protein will not, however, cause kidney dysfunction in people with healthy kidneys.

With respect to bone health in older adults, it was previously believed that high protein intake would lead to osteoporosis via inducing chronic metabolic acidosis (too much acid in the blood from the protein). Multiple studies have since failed to show that high protein intake causes loss of bone density and fractures.

Another concern with a high protein diet — especially for those on a low-carb diet — is that the amino acids in dietary protein could cause a significant rise in blood sugar.

With respect to lifespan, data from flies, mice, and other animals suggest that restricting protein may increase longevity, while human data are very weak.

High protein diets are safe for most people. The bottom line is, there is no convincing evidence that high protein diets are harmful — although they are not recommended for people who already have severe underlying kidney disease. You can read more in our guides on bone health and kidney health, as well as our guides on red meat and diet and cancer.

Animal versus plant protein

Is all protein the same? No, not really.

Animal proteins are considered complete sources of protein — meaning they supply all nine essential amino acids — whereas all plant sources aside from soy are incomplete.

Your body also absorbs animal proteins much better than most plant proteins, meaning you can eat less for the same effective amount of protein. Again, that doesn’t mean you can’t get adequate protein from plant sources. But it does mean you may need to increase your intake goals by 20% or more.

Lastly, plant sources of protein tend to be higher in carbohydrates than animal sources. If you follow a very low-carb or keto diet, this can make meeting all your goals challenging.

Soy is unique among plant proteins since it is a complete protein and appears to have similar bioavailability, muscle-building effects, and weight loss benefits as animal proteins.

However, aside from soy, evidence suggests animal protein may be more beneficial for strength and muscle maintenance and may provide a better source of micronutrients, especially from red meat.

Longevity and chronic diseases

With respect to lifespan, some observational studies have suggested that plant protein may be associated with better longevity, while animal protein may correlate with earlier death.

These observational studies are considered very weak evidence. At this time, we cannot say that there is sufficient evidence to recommend getting most of your protein from either plants or animals. It is our opinion that eating a diversity of plant and animal sources of protein should be considered a healthy diet.

Summary: Animal versus plant proteins

- Animals provide complete proteins with better absorption and muscle-building benefits.

- Plant proteins can be combined to form complete proteins but may contain more calories and carbs per gram of protein.

- The data on longevity and chronic diseases may raise concerns about animal protein, but the majority of human evidence is low-quality and inconclusive.

7. FAQ about high protein diets

We get it. All this new information about protein can be confusing. If you have additional questions about why or how to add more protein to your meals, check out our FAQ with the “Top 20 questions about high protein diets.”

Start your FREE 30-day trial!

Get instant access to healthy low-carb and keto meal plans, fast and easy recipes, weight loss advice from medical experts, and so much more. A healthier life starts now with your free trial!

Start FREE trial!High protein recipes