Promoting low carb in health care

At the Low Carb USA 2017 conference, Dr. Andreas Eenfeldt fielded a question from an ER nurse about health professionals promoting the low-carb lifestyle. She described the dilemma of feeling that her hands are tied when dealing with patients with type 2 diabetes in the hospital due to the protocols and standards in place, making her feel that she is unable to share valuable low-carb advice with them. As a physician working in the hospital setting, I’d like to add my own advice in addition to what Andreas recommended.

Feeling helpless in health care

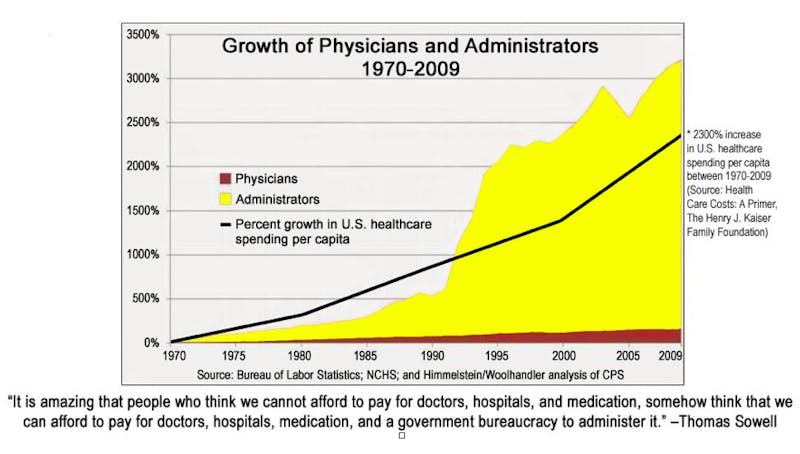

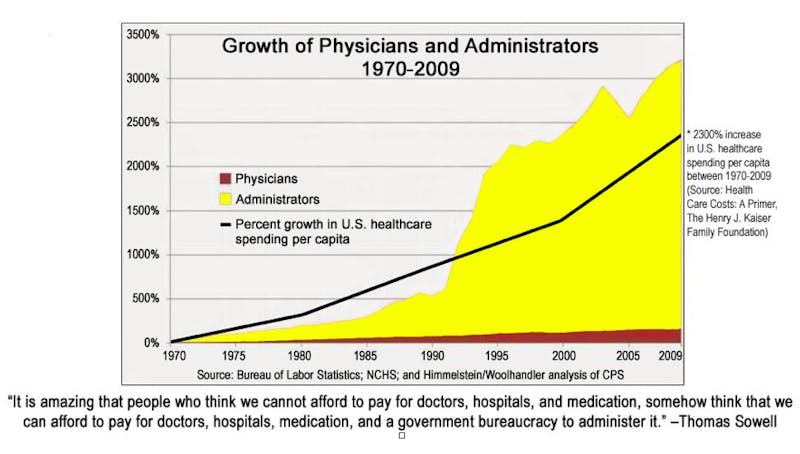

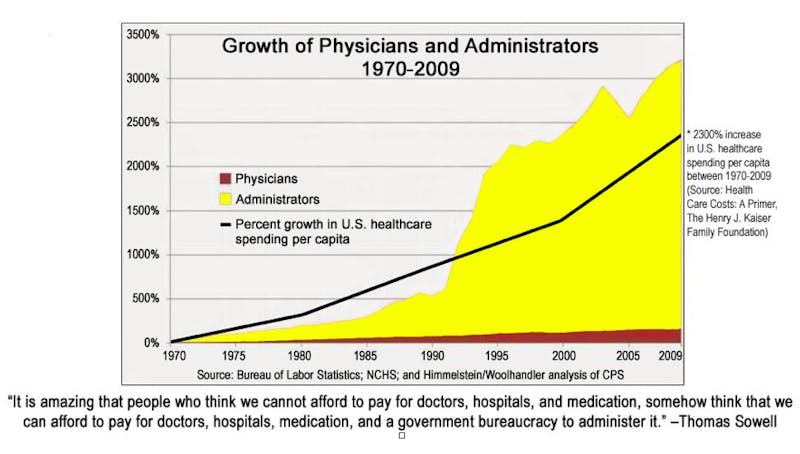

It’s easy to feel helpless in the hospital setting when you recognize potentially ineffective practices being utilized, and that feeling of helplessness seems only to get worse as there are more and more administrators who are out of touch with the reality of front-line patient care. It’s the age-old problem of too many talkers and too few doers.

But, let’s face it…It’s not possible for rational beings to sit back while patients are being slighted with outdated and unscientific methodologies simply because “that’s just the way it’s always been done.”

Health care is driven by guidelines and protocols

There are few things more frustrating than having to witness guidelines and protocols that don’t actually address the underlying problem, e.g. insulin protocols that are automatically started on any patient with an elevated glucose. That said, hospitals need to have standardized protocols in place to ensure that all patients be given a minimum standard of care – for example, to ensure that potentially dangerous hyperglycemia or hypoglycemia gets addressed in a prompt manner.

The sad truth is that an unacceptably large percentage of patients with type 2 diabetes do not make a reasonable effort to control their glucoses and thus present to the hospital with out-of-control diabetes and terrible associated complications. Protocols that utilize insulin to treat hyperglycemia serve as a “Band-Aid” for these neglectful patients with type 2 diabetes who are in desperate need of help and as a failsafe mechanism for those who already have adequate control over their diabetes.

“Wait, you said the glucose was 500 mg/dl (27.8 mmol/L) and there was no evidence of DKA (Diabetic Ketoacidosis) . . . but you started the patient on an insulin drip? Oh boy…”

Elsewhere in the hospital, there are education protocols that are employed by diabetes educators who follow a predictable script based on the standards of care established by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) – protocols that similarly fail to address the underlying problem.

The world of nutrition is full of conflicting advice

Nutrition, in particular, is an emotionally-charged topic. Case in point: if you want to aggravate me, tell my patients with type 2 diabetes that they need to eat carbs.

It’s apparent that medicine is in a crossroads in regards to nutrition. There is discontent over the lack of scientific rigor in the US Dietary Guidelines, and increasingly large numbers of people are finding that they can achieve optimal health by ignoring all the advice they’ve ever learned. Let’s face it: there will never be universal agreement on nutrition.

Knowing that my patients with type 2 diabetes will inevitably be confronted with polar-opposite dietary advice from what I have told them, I preemptively alert them to what is bound to happen before they are seen by the cardiologist, dietitian, diabetic educator, or whomever. I explain what dietary advice they will likely hear (very predictable) and why, in contrast, my advice makes more sense for them in a particular situation.

Patients are free to make their own judgments, and I certainly encourage them to do their own research and ask whatever questions they might have. There is an abundance of information available to anyone with internet access; one just needs to be able to sort out the snake oil salesmen from the well-intentioned, reputable sources.

Tips for promoting low-carb

What, then, can someone do in a health care setting to promote the low-carb lifestyle to patients who are likely to benefit? I recommend the following approaches.

Give irrefutable advice. There are a few pieces of advice that you can safely dispense to patients without fear of retaliation.

- You can’t go wrong saying something to the effect of: “Carbohydrates increase your glucose, and thus eating fewer carbs can help lower your glucose.” No one has a legitimate argument with this basic scientific fact, especially because everyone preaches the corollary, “If your glucose is too low, you need to eat some carbs.”

- Recommend unprocessed or minimally processed food – which happens to be a way of eating that is naturally lower in carbs than the Standard American Diet. If the patient has diabetes, however, then attention should be paid to restricting carbs as well. Similarly, no one can mount a sound argument against advice to avoid highly processed food.

Collaborate with the treatment team. Ideally, you want permission from the attending physician (or emergency department physician) to offer advice to the patient, since the attending physician is ultimately responsible for the patient’s care. For example, in my work setting, nurses are comfortable discussing and encouraging carbohydrate restriction with patients under my care, because they know that I’ll defend them in the event of any complaint about it. Depending on physicians’ own interest in educating their patients about nutrition, there may or may not be freedom to discuss a low-carb approach. In general, though, most physicians are not very engaged in discussions about nutrition with their patients.

Be mindful of the hospital/department culture. Are your hands really tied, or is that just a perceived limitation? Different hospitals, and even different departments within the same hospital, may have a lot of variance as to the “rules of engagement” in this situation. Ask your coworkers; test the waters; when in doubt, tread lightly.

Ask for an explanation of specific interventions. Feel free to ask the attending physician for explanations of particular interventions as they pertain to your patients, as well as why they are not utilizing a low-carb approach. In this era of electronic medical records that are rife with order sets, it may be that there are unintended orders on the chart or orders generated somewhat mindlessly due to initiating a particular protocol. An innocent inquiry into a particular order may stimulate a constructive discussion and reassessment of the situation. For example, you may ask if insulin is really necessary to manage moderate hyperglycemia, or if a simple dietary restriction (carbs) might be adequate for a patient? Let them know that you are interested in helping to explain the rationale for restricting carbs to patients who are struggling to control their diabetes. Everybody wins.

Refer patients and families to DietDoctor.com or other reliable resources. Nearly everyone is carrying a smartphone these days, and hospitals usually offer free wi-fi access. Furthermore, there is [hopefully] plenty of downtime at the hospital during which patients may utilize a site like this to discover a new, life-saving perspective on managing their health. In addition to writing down the website address for my patients on one of my business cards, I also frequently share articles and handouts that might be relevant to a patient’s situation and encourage them to write down questions that may come up after reviewing such information.

Encourage discussion and consideration of different approaches among the health care team.

- Ask physicians if they’re familiar with new journal articles relevant to low-carb concepts; you could even go the extra step by handing them a copy of the article.

- Inquire about treatment strategies: “I’ve done some reading and have learned that there is no good evidence to support . . .”; “What kind of evidence is there to support that diet for patients with type 2 diabetes?”; “Are there any good RCT’s (Randomized Controlled Trials) that support that approach?”

- Encourage further reading/research among your patients and coworkers.

Share anecdotes about low carb successes. Even better, get people asking about how you achieved your own transformation. Everyone loves a good story. Inspire others by detailing the benefits that individuals have realized, whether it be weight loss, reversal of diabetes, or simply improvements in glycemic control in the hospital on a carbohydrate-restricted diet. Even more inspiring, though, is a demonstration of you putting your money where your mouth is, by showing everyone what can be achieved by living the low-carb lifestyle.

Empower your patients. Perhaps the most important thing one can do for patients with type 2 diabetes being admitted to the hospital is to empower them – let them know what to expect and let them know that they have options. Insulin is not the only way to treat hyperglycemia, and it certainly isn’t the safest. Remind patients that they can say “no” to interventions. Give them tips on eating low carb in the hospital.

Get involved in hospital policy. Work to make the changes that you envision. For real impact on patient care, there needs to be changes to hospital policy. Join a committee that addresses diabetes or nutrition. Talk with administration about your concerns and alert them to the potential to improve patient care. Create a strong “Why” message, identify the important stakeholders, and work to get buy-in from the stakeholders who can effect change.