Controversy and consensus in Zurich: Evidence, individualization and diabetes reversal

Diabetes roundtable at Swiss Re Institute, June 17. Photo: Eric Westman.

What happens when a collection of prominent voices from across the world have an opportunity to hear and discuss their divergent views on nutrition and health? Spoiler alert: no fistfights. But there were dozens of pointed remarks, a smattering of defensiveness, and enough oversimplifications to go around. Certainly, Swiss Re Institute’s back-to-back meetings on “the science and politics of nutrition“ and on “redefining diabetes” left everyone who attended or followed remotely with a lot to think about.

As a reinsurance company with an interest in helping people live longer, healthier lives, Swiss Re had already published a 2016 report challenging conventional thinking about nutrition guidance. In order to try to address ongoing controversies over the role that food plays in long-term health, they hosted a four-day meeting in Zurich that Fiona Godlee, editor-in-chief of the BMJ, called a “miracle.” The BMJ issued a special edition of open-access articles related to the meeting, and Godlee raised the hope that conversations in that issue and at the meeting could lead to some common ground. And indeed agreement was found; it just wasn’t very common.

Divergent opinions

Divisions in thought were apparent immediately. The most obvious one was the split between those in favor of higher-carb diets that limit saturated fats and meat and those who see lower-carb diets, which often include animal fats and meat, as healthy. Two related concerns polarize these camps: the effects of saturated fat and the effects of carbohydrates, respectively, on health.

First up, saturated fat. Cambridge epidemiologist Nita Forouhi had the thankless task of trying to wrestle this science—and the competing perspectives of Harvard epidemiologist Walter Willett and author Gary Taubes — into a coherent picture. All parties, including Ronald Krauss, a heart disease researcher who was not in attendance, did agree that trans fats are bad, omega-3 good, and limits on total fat unnecessary.

As to the health effects of saturated fat and the importance of LDL-cholesterol levels, interpretations of the science remained divided with no resolution in sight. This lack of clarity has important implications for dietary guidance. If there is no strong scientific reason to restrict saturated fat, then lower carb diets that allow its use can’t accurately be described as “unhealthy.”

When it came to carbs, nutrition scientist Jennie Brand-Miller surprised the audience by acknowledging that there is “no known minimum requirement” for dietary carbohydrate. Although she ultimately concluded that the best diet was one based on “low-glycemic” foods — an approach that would include low-carb diets — she argued that low-carb diets were “difficult” and “hard to follow.” Testimony from audience members who reversed their type 2 diabetes on such diets demonstrated that this was clearly not necessarily the case.

Other fault lines were more subtle, but closely related to the “sat fat vs. carbs” debate. These divisions were over what science counts when answering questions about diet-disease relationships. It was clear that the conclusions someone drew from the “totality of the evidence” depended on how that person felt about the kind of science that provided it.

The shortcomings of nutrition science

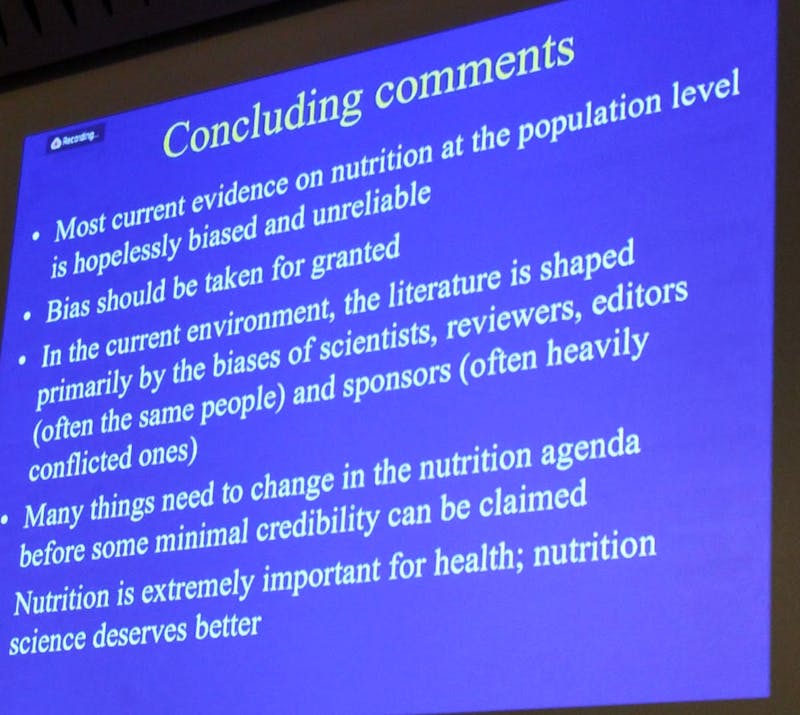

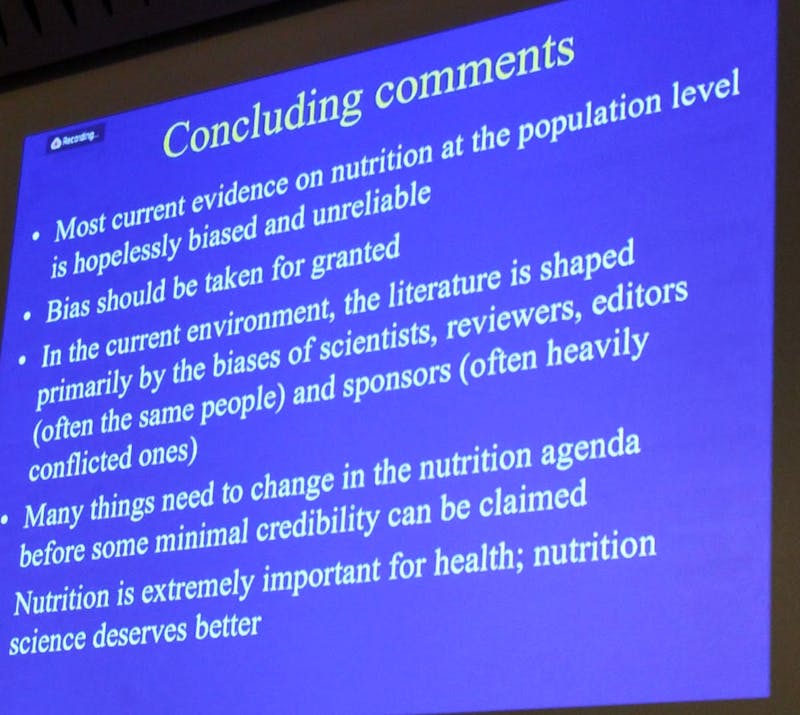

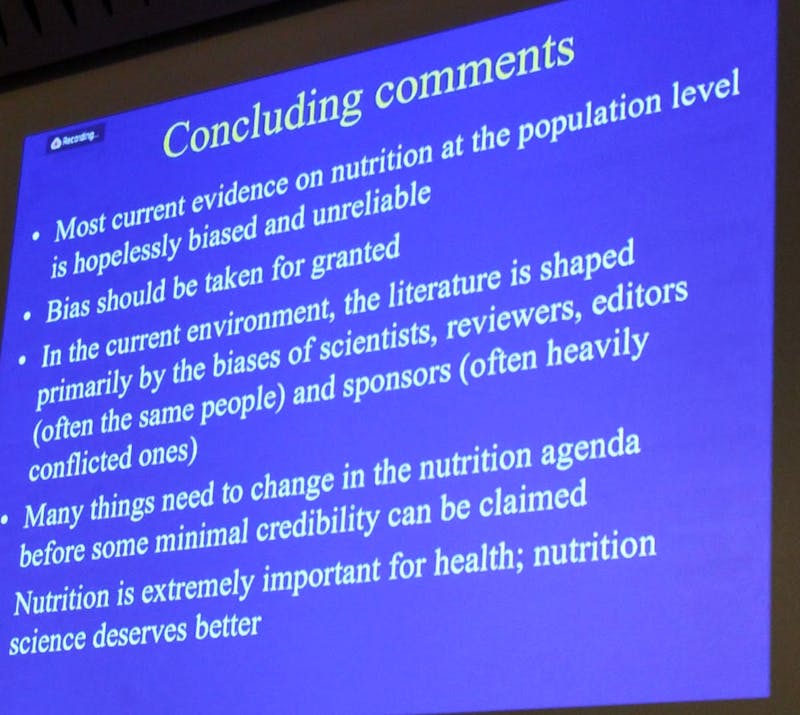

Stanford scientist and perennial critic of poor research, Professor John Ioannidis, pulled no punches in pointing out the shortcomings of nutrition science, concluding that many findings were “incompatible with logic” and most population-level evidence “hopelessly biased and unreliable”. His final slide can be seen below:

Professor Ioannidis highlighted the limitations of observational studies and also voiced concerns about clinical trials, using the recently retracted PREDIMED study as an example.

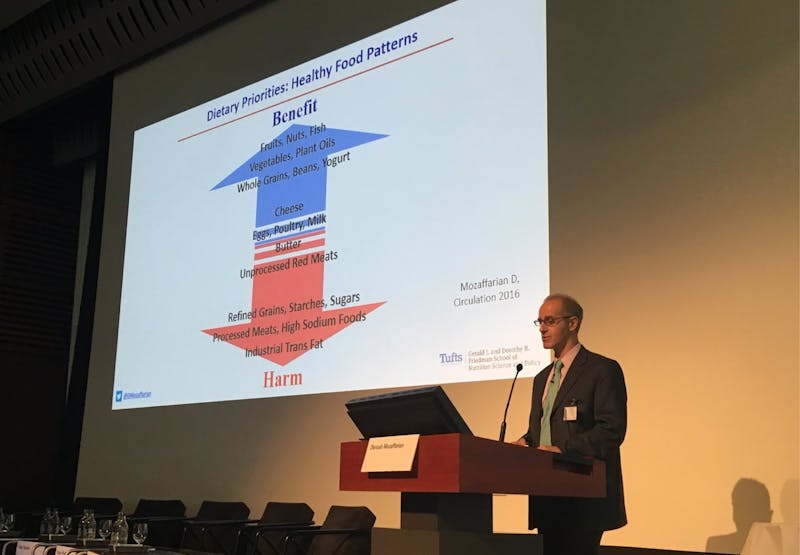

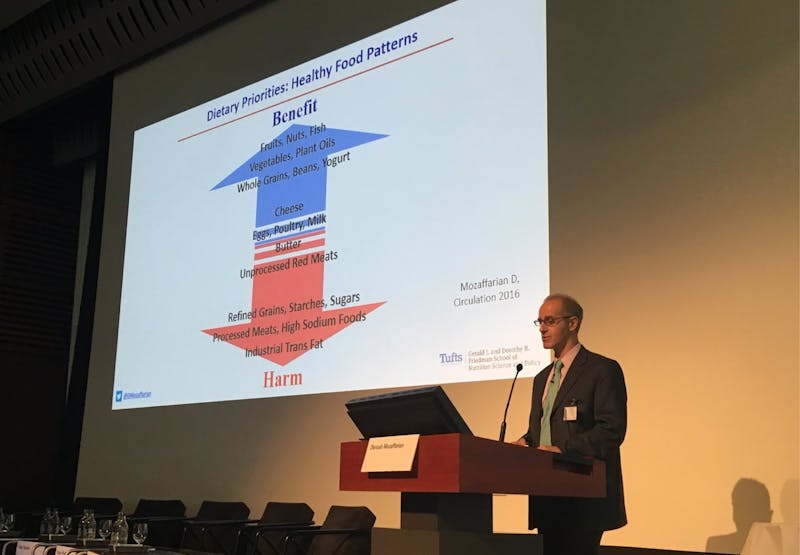

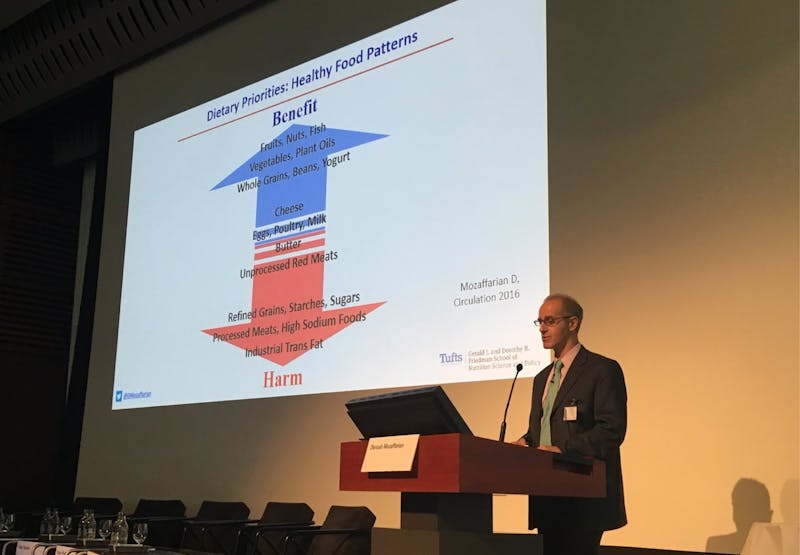

With that in mind, it might seem reasonable to consider, as U.K. physician David Unwin asked a panel, how the experiences of clinicians who treat diabetes with therapeutic diets might fit into the picture. This was dismissed by Dariush Mozaffarian of Tufts as “the worst kind of observational evidence,” and Willett defended Harvard’s brand by bringing up issues of environmental sustainability, but other presenters suggested that nutrition science needed to pay more, rather than less, attention to individuals.

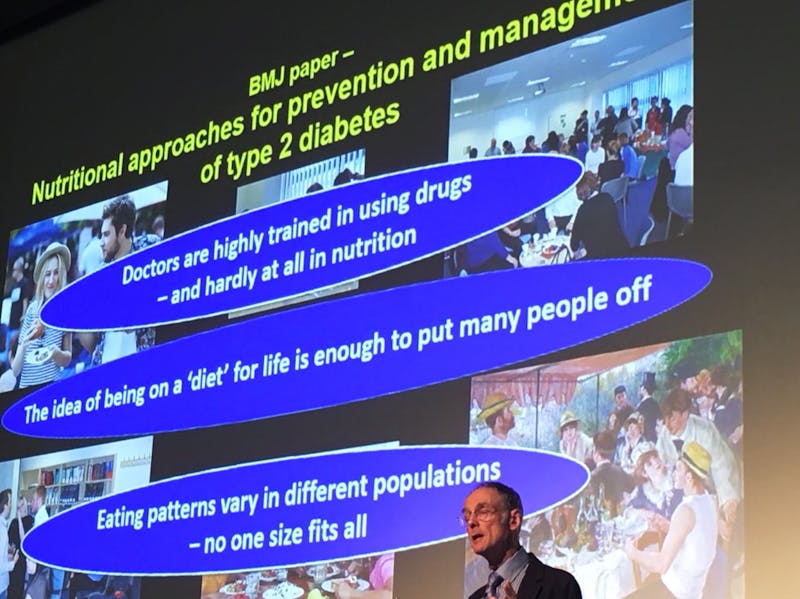

One of the clear areas of consensus was that diets should be individualized. In his studies of the microbiome at King’s College London, Tim Spector has shown how, even in twins, reactions to foods can differ dramatically. Other speakers addressed how economic resources, food traditions, and cultural preferences might affect what diet “works” for a particular person. The emphasis on individual differences suggested that a “one size fits all” diet promoted in national dietary guidelines is not likely to be right for everyone, and it may be, as cardiologist and epidemiologist Salim Yusuf argued, that much higher standards of evidence are needed before such guidance is “inflicted” on a population.

For people who struggle with glucose intolerance, excess weight, or insulin resistance, an entirely different approach—or more accurately—a variety of approaches may be needed.

Reversing type 2 diabetes

This highlights another strong point of consensus: Reversal of type 2 diabetes is possible, and there are lots of ways to do it. But what all of these ways have in common is that they begin with limiting refined starches and sugar.

Roy Taylor’s DIRECT trial brought “diabetes reversal” a mainstream respectability it hadn’t had before. Using a very low-calorie diet, Taylor showed that he could “cut the head off” the vicious cycle of insulin resistance and insulin production that results in type 2 diabetes. Of course, to Sarah Hallberg and Stephen Phinney of Virta Health, this was old news. Their individualized ketogenic diet has shown remarkable results in getting people off of diabetes medication and normalizing HbA1c levels.

Megan Ramos, from the Intensive Dietary Management program, demonstrated similar results with an individualized intermittent fasting approach, which she says works well for those with limited incomes, physical restrictions, minimal cooking skills, or emotional or cultural attachments to carbohydrate foods.

Another point of agreement: weight loss is not necessary to see dramatic results. With reduction of carbs, elimination of medications happens in weeks or even days, long before significant weight loss is seen. Hallberg sees weight loss as a “side effect” rather than a goal, a hopeful note for those who struggle with the scale but still want to avoid the damaging complications of diabetes. As global rates of diabetes climb, this may be what is needed as much as anything else: hope.

Because both sides tend to overstate the strengths of their positions and ignore the weaknesses, the meeting was frustrating at times. Still, the burden of proof has shifted. The argument that sat fat should be replaced by vegetable oils has been the biggest obstacle to the acceptance of lower-carb, whole food diets as healthy. But with no clear scientific consensus to indicate that sat fat is unhealthy, academic researchers who ignore the personal experiences of individuals who have regained their health on such diets must now be the ones to justify their continued insistence on this stance.

The Swiss Re Institute should be congratulated for making this clear: it is the role of nutrition science, in all its forms, to help individuals by lowering, rather than raising, barriers for improving health outcomes. Fostering hope for reversal for type 2 diabetes and increasing patient choice for achieving this goal must be prioritized over the defense of out-dated dogma that does not serve the needs of the public.