Too much protein? Potential concerns and side effects

Are there risks to high-protein diets? The short answer is yes, but the risks are quite low. While anything consumed in excessive amounts – even water – can cause problems, most people eating a high-protein diet will not suffer any major negative effects.

We know there are definite advantages to eating more protein, as we detail in our main guide, “What are high-protein diets,” but what about the potential concerns and challenges?

This guide examines the most common concerns about a high-protein diet and explains whether scientific evidence supports them.

We also explore the practical considerations and challenges you may face when increasing your protein intake.

Risks and concerns

Will more protein hurt my kidneys?

Many people, including some healthcare professionals, worry that high-protein diets are harmful to kidney health.

While that may be true for those who already have advanced kidney disease, there is no evidence to suggest this is true for those with normal kidney function or mild to moderate kidney disease.

Regarding kidney stones, very-high animal protein diets (more than 2 grams/kg/day) have been associated with an increased risk of uric acid stones.1

We cover all of this in detail, including the risk for kidney stones, in our guide on low-carb diets and kidney health; below we describe some of the relevant studies.

One study reports no harmful effects to bone and kidney health after one year of eating a high-protein diet of 3 grams of protein per kilo of body weight per day.2

The following meta-analysis of nine RCTs and a separate, large observational study report that those who ate higher amounts of protein had a significantly reduced risk of developing kidney disease.3

If you have advanced kidney disease, make sure you check with your physician before increasing your protein intake, as the general recommendation is to reduce protein intake in that setting. Otherwise, there is no credible evidence that high-protein diets hurt kidney function.

Will more protein hurt my bones?

One reason people speculate that more protein may be harmful to bone health is that higher protein foods, especially from animal sources, could lead to more acidic blood which, in theory, could harm our bones. However, the mechanistic data upon which this hypothesis is based have been questioned and – to a large extent – refuted.4 And the majority of clinical data suggest higher protein intake is beneficial, not harmful, to bone health.5

One review of the literature reports that a higher-protein intake (greater than current recommended levels of 0.8 grams per kilo of body weight per day) may be beneficial for the maintenance of bone health and the prevention of bone loss in older adults.6

Because protein makes up approximately 50% of bone volume, it makes sense that we need adequate protein supplies to maintain healthy, strong bones.7

Will more protein hurt my blood sugar?

One concern with a high-protein diet — especially for those on a low-carb diet — is that the amino acids in protein get converted to glucose via gluconeogenesis. Could eating more protein, therefore, lead to higher blood glucose levels?

Well-conducted physiological studies show that protein is not a meaningful contributor to higher blood glucose in healthy individuals or those with type 2 diabetes.8

One study evaluated a meal with 50 grams of protein and didn’t find a significant increase in blood sugar.9

Two other studies report that a diet with 30% of calories from protein improved glycemic control, and protein has been shown to lower blood glucose in other studies of people with type 2 diabetes.10

For people with type 1 diabetes, it is important to note that protein has been found to increase late post-meal blood sugars when consumed along with dietary carbohydrate. In the absence of dietary carbohydrate, protein amounts up to 50 grams do not seem to raise post-meal blood glucose, while 75-100 grams of pure protein can raise blood glucose in a similar fashion to 20 grams of carbohydrate.11

Will more protein raise my insulin levels and make me gain weight?

Although some fear the potential for higher insulin levels with protein, scientific studies don’t support this concern. Protein may briefly increase insulin concentrations, but high-protein diets are not known to cause hyperinsulinemia (chronically high insulin levels). In fact, for people with prediabetes or type 2 diabetes, a higher protein diet may be more beneficial than a lower protein one.12

Most studies of high-protein diets demonstrate improved weight loss, even for people most susceptible to insulin resistance/hyperinsulinemia — those with type 2 diabetes.

Who should avoid high-protein diets?

Although increasing protein can help many people with their health goals, some people should be cautious about their protein intake.

Anyone with advanced kidney disease should likely avoid high-protein intake and should consult with their healthcare provider for guidance.

The same is true for anyone using a keto diet as part of their treatment plan for seizures, mental health disorders, dementia, or cancer therapy. While the evidence is still in early stages, it suggests that higher fat intake with resultant higher ketone levels may provide more benefit in these therapeutic situations.

The key takeaway is that if you are using a keto diet to treat a specific medical condition, you shouldn’t do it alone. And you shouldn’t add more protein to your meals without checking with your physician.

If you need to find a low-carb friendly clinician, you can start with our find a doctor map to make sure you are getting adequate guidance and support.

Will more protein shorten my life?

One of the hottest concerns about protein is understanding what effect it has on human longevity. Animal data suggest that lower protein diets can improve longevity, although the implication for human diets is unclear.13

The data suggesting animal protein intake leads to diabetes, heart disease, or even premature death are low-quality and should not be used to make conclusive arguments. To date, there is no high-quality evidence that animal protein worsens health or causes premature death.14

Even if one believes the hypothesis that eating more protein reduces longevity, we still don’t know how to quantify the impact for an individual. Will it reduce your life expectancy by months? One year? One decade? And what are the trade-offs with respect to the beneficial effects of increased protein intake: weight loss, metabolic improvements, and improved healthspan?

We conclude that, based on the current level of evidence, the benefits of higher protein diets outweigh the potential drawbacks for the overwhelming majority of people.

Is eating more animal protein bad for my health?

Animal protein sources, most notably red meat, have been implicated in an increased risk of heart disease, cancer, type 2 diabetes, and early death. However, as we cover in our detailed guides on red meat and another on diet and cancer, the data against animal foods are very weak and do not support strong conclusions.15

Even using the poor quality data, it is unclear what impact animal foods have on an individual’s health since the overall risk reported for large populations is so minimal.16

However, when looking at higher quality evidence, there is no support that animal food sources are less healthy.

Can I overdo it on a high-protein diet?

You may wonder how much is too much protein or what will happen if you eat too much protein.

Based on calculations of the liver and kidney’s ability to safely handle protein, a 176-pound (80-kilo) person has a theoretical maximum of 365 grams of protein per day.17 That’s 73% of a 2,000 calorie diet! It’s safe to say that most people won’t have to worry about overeating protein.

However, if you happen to eat more protein than your body can safely handle, you will start to experience nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and other unpleasant symptoms.18 In other words, you are likely going to notice.

Challenges

How do I calculate my recommended protein intake?

The typical reference point for protein intake is the Recommended Daily Allowance (RDA) for daily protein, which is 0.8 grams per kilo.19 For an average 154-pound person (70 kilos), that equates to 56 grams of protein per day — about 6 ounces of steak. For women, the RDA is even less, around 46 grams.

However, the RDA recommendation addresses the minimum amount required to prevent protein deficiency. Preventing protein deficiency is not the same thing as the recommended amount for improving your health — a distinction that many people misunderstand.20

We recommend 1.6 to 2.0 grams per kilo of reference body weight per day on a higher protein diet.21 That usually equates to around 30% of your calories from protein.

| Height | Women | Men |

|---|---|---|

| Under 5’4″ ( < 163 cm) | 90 grams | 105 grams |

| 5’4″ to 5’7″ (163 to 170 cm) | 100 grams | 110 grams |

| 5’8″ to 5’10” (171 to 178 cm) | 110 grams | 120 grams |

| 5’11” to 6’2″ (179 to 188 cm) | 120 grams | 130 grams |

| Over 6’2″ (188 cm +) | 130 grams | 140 grams |

If you are very physically active, over 50 years old, or most of your protein comes from plant sources, you may want to increase your protein even more than indicated above. Adding about 20-30 grams more per day will take you to the upper end of the 1.6 to 2.0 grams per kilo of reference body weight.

How do I know if a high-protein diet is appropriate for me?

Are you doing great with your current diet? Are you succeeding in your health goals and maintaining a healthy weight? Do you have plenty of energy? Are you free from struggling with hunger or cravings?

If you answered “yes” to all of these questions, you likely don’t have to change anything in your diet. But if you are not succeeding in any of these areas, increasing your protein intake may benefit you.

Studies show that higher protein diets can help people lose weight and improve body composition, metabolic health, and bone health.22 Higher protein diets can also improve satiety and decrease hunger.23 Lastly, higher protein diets can reduce the risk of frailty and sarcopenia as you age.24

If you are looking to improve any of these health metrics, as mentioned above, it may be worth trying a higher protein diet and see how you respond.

What if I feel hungry on a high-protein diet?

Some people who transition from a high-fat keto diet to a higher protein diet may notice increased hunger — at least in the beginning. This was the experience of some Diet Doctor team members when they experimented with a higher protein diet.

First, the good news. The increased hunger was temporary for most Diet Doctor team members. It was also easily addressed by adding high-protein snacks to calm hunger.

If you highly value the convenience of only eating twice a day without any snacks, then feeling hungry on a high-protein diet may be a deterrent. But before you abandon high-protein eating, make sure you are eating enough fiber-rich veggies and that you are getting enough overall calories, from both carbs and fats, to help ease your hunger.

Can I eat a high-protein diet if I eat a plant-based diet?

You absolutely can eat a high-protein diet even if you are plant-based. As our guides on high-protein foods and another on high-protein snacks show, plant-based foods like beans, lentils, peas, pumpkin seeds, and soy are good high-protein choices.

However, plant-based proteins tend to contain more carbohydrates and calories than the same amount of protein from animal sources. So, it may be difficult to increase your protein if you follow a very low-carb plant-based diet.

If you are looking for inspiration, here are some of our favorite plant-based high-protein recipes.

Plant-based high-protein recipes

What if I have a hard time reaching my protein target?

Some people may struggle to increase their protein. If you’ve lived your whole life thinking two eggs (12 grams of protein) make up a high-protein breakfast, changing that to four eggs (24 grams of protein) may seem daunting.

One solution is to add high-protein snacks to your meals or eat them between meals (as long as snacking doesn’t stimulate you to eat more calories than necessary).

Another option is to make a protein powder smoothie. Although our bias is to recommend whole foods first, we acknowledge that protein powders play an important role in helping some people reach their protein targets.

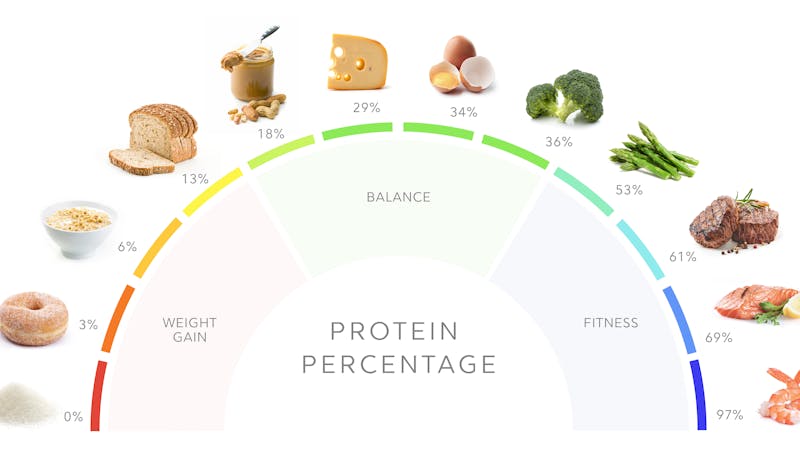

You can also make a few key dietary swaps to help increase the protein percentage of your foods.

For instance, you could switch out regular cheese for low-fat cheese or even cottage cheese. Or, instead of eating regular yogurt, go for low-fat Greek yogurt. You could also swap your bacon for Canadian bacon or turkey bacon. These swaps allow you to consume protein with fewer other calories, thereby providing more “room” in your diet for additional protein-containing foods.

Learn more in our guide of the top high-protein foods.

What if eating more protein becomes too expensive?

High-quality protein foods likely will cost more than lower-quality, processed, low-protein foods. That is an unfortunate reality.

But you can utilize strategies to save money. Buy in bulk whatever is on sale. One week may be pork chops; another may be chicken thighs and another ground beef. If you don’t want to eat it all right away, store the extras in the freezer for later.

Focus on less expensive options like canned fish, eggs, cottage cheese, or even protein shakes.

If you plan on eating out, consider eating inexpensive protein foods at home first, so you don’t have to pay for extra protein at the restaurant.

Being creative and flexible can help you find the best deals and increase your protein without breaking the bank.

What if I find high-protein eating boring or too restrictive?

When you hear the words “high protein,” do you think dry chicken breasts with plain steamed broccoli? If so, it doesn’t have to be that way!

Remember, a high-protein diet doesn’t have to be a low-fat diet, and it doesn’t have to mean eating boring “diet food.”

Eat chicken with the skin. Eat a ribeye steak. Add cheese, butter, or olive oil to your veggies. Eat a combination of whole eggs and egg whites with plenty of veggies and some cheese.

Don’t be afraid of adding fat to your high-protein foods — add just enough to enjoy your food and not more than you need.

What if I don’t like to cook?

You might have to cook more frequently, especially if you want to increase your protein intake without breaking the bank. But you can save time with batch cooking and refrigerating or freezing leftovers to eat later.

You can also choose higher protein options that don’t require cooking — canned tuna, sardines, cold cuts, and packaged lupini beans are quick and easy options.

Eating high protein — the next steps

After reading this guide about the potential concerns and side effects of a high-protein diet, are you ready to get started increasing your protein intake? If so, start by reading our introductory guide to high-protein diets. There you will learn practical tips on how to get started, plus information on all the potential benefits of a high-protein diet.

You can also read the top 20 questions and answers about a high-protein diet.

Happy eating!

Popular now

Too much protein? Potential concerns and side effects - the evidence

This guide is written by Dr. Bret Scher, MD and was last updated on June 19, 2025. It was medically reviewed by Dr. Michael Tamber, MD on July 18, 2022.

The guide contains scientific references. You can find these in the notes throughout the text, and click the links to read the peer-reviewed scientific papers. When appropriate we include a grading of the strength of the evidence, with a link to our policy on this. Our evidence-based guides are updated at least once per year to reflect and reference the latest science on the topic.

All our evidence-based health guides are written or reviewed by medical doctors who are experts on the topic. To stay unbiased we show no ads, sell no physical products, and take no money from the industry. We're fully funded by the people, via an optional membership. Most information at Diet Doctor is free forever.

Read more about our policies and work with evidence-based guides, nutritional controversies, our editorial team, and our medical review board.

Should you find any inaccuracy in this guide, please email andreas@dietdoctor.com.

Clinical Nutrition Research 2015: Nutritional management of kidney stones (nephrolithiasis) [overview article; ungraded] ↩

We recommend 1.2 to 2.0 grams of protein per kilo of body weight per day for adequate intake. Our recommendation for higher protein intake is 1.6 to 2.0 grams. So we consider a diet of 3 grams per kilo a very high-protein diet.

Journal of Nutrition and Metabolism 2016: A high-protein diet has no harmful effects: a one-year crossover study in resistance-trained males [randomized trial; moderate evidence] ↩

British Journal of Nutrition 2016: Impact of low-carbohydrate diet on renal function: a meta-analysis of over 1000 individuals from nine randomised controlled trials [systematic review of randomized trials; strong evidence]

American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2021: Causal effects of relative fat, protein, and carbohydrate intake on chronic kidney disease: a Mendelian randomization study [nonrandomized study, weak evidence] ↩

British Journal of Nutrition 2013: Nutritional disturbance in acid-base balance and osteoporosis: a hypothesis that disregards the essential homeostatic role of the kidney[overview article; ungraded] ↩

Nutrition Today 2019: Optimizing dietary protein for lifelong bone health [overview article; ungraded]

International Journal of Vitamin and Nutrition research 2011: Protein intake and bone health

[overview article; ungraded]American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2008: Amount and type of protein influences bone health

↩

[overview article; ungraded]The following meta-analysis of observational studies and RCTs shows an association between higher protein intake and reduced bone fracture risk in the elderly.

Computational and Structural Biotechnology Journal 2019: High versus low dietary protein intake and bone health in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis [meta-analysis of observational studies and one RCT, very weak evidence] ↩

Nutrition Today 2019: Optimizing dietary protein for lifelong bone health [overview article; ungraded] ↩

Diabetes 2013: Dietary proteins contribute little to glucose production, even under optimal gluconeogenic conditions in healthy humans. [nonrandomized trial; weak evidence] ↩

Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 2001: Effect of protein ingestion on the glucose appearance rate in people with type 2 diabetes [randomized trial; moderate evidence]

The trials included in this review of RCTs did not restrict protein intake and showed significant improvement in blood glucose levels and metabolic health.

BMJ Open Diabetes Research and Care: Systematic review and meta-analysis of dietary carbohydrate restriction in patients with type 2 diabetes [strong evidence]

↩Diabetes 2004: Effect of a high-protein, low-carbohydrate diet on blood glucose control in people with type 2 diabetes [randomized trial; moderate evidence]

American Jopurnal of Clinical Nutrition 2003: An increase in dietary protein improves the blood glucose response in persons with type 2 diabetes [randomized trial; moderate evidence]

Diabetes Care 2006: Protein hydrolysate/leucine co-ingestion reduces the prevalence of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetic patients [randomized trial; moderate evidence]

Protein may slightly increase insulin concentrations acutely, but high-protein diets are not known to cause hyperinsulinemia (chronically elevated insulin levels).

Diabetes care 2003: Amino acid ingestion strongly enhances insulin secretion in patients with long-term type 2 diabetes. [nonrandomized trial; weak evidence] ↩

Diabetes Care 2015: Impact of fat, protein, and glycemic index on postprandial glucose control in type 1 diabetes: implications for intensive diabetes management in the continuous glucose monitoring era [systematic review; strong evidence] ↩

Diabetes care 2003: Amino acid ingestion strongly enhances insulin secretion in patients with long-term type 2 diabetes. [nonrandomized trial; weak evidence] ↩

EBioMedicine 2019: The impact of dietary protein intake on longevity and metabolic health [overview article; ungraded] ↩

Multiple low-quality nutritional epidemiology studies show that consuming plant protein correlates with less risk of dying than animal protein intake. However, all of these studies suffer from inherent methodological weaknesses, and higher-quality studies are lacking.

JAMA Internal Medicine 2016: Association of animal and plant protein intake with all-cause and cause-specific mortality [nutritional epidemiology study with HR<2; very weak evidence]

One observational study reports that eating more animal protein, but not plant protein, is associated with a higher risk of death in people ages 50 to 65. The same correlation did not hold for those older than 65.

However, the data do not differentiate whether the protein type caused the higher risk for the specified age group or if it was because of confounding variables, such as healthy user bias. The people who chose plant sources of protein had a much lower incidence of diabetes at baseline compared to the higher protein group (2% vs. 17%).

The main mortality difference was diabetes mortality, which may have had more to do with that underlying health condition than the type of dietary protein.

Cell Metabolism 2014: Low protein intake is associated with a major reduction in IGF-1, cancer, and overall mortality in the 65 and younger but not older population [nutritional epidemiology study and animal study; very weak evidence]

Some observational studies report no mortality difference between vegetarians and meat-eaters, though this should also be considered very weak evidence.

American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2009: Mortality in British vegetarians: results from the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC-Oxford) [nutritional epidemiology study; very weak evidence]

↩The following are low-quality nutritional epidemiology studies that suggest a minimal increased risk with red meat intake. However, as we discuss in our guide on observational vs. experimental studies, this line of evidence is complicated by healthy user bias, poor data collection, confounding variables, and other methodological weaknesses.

British Journal of Nutrition 2014: Association between total, processed, red and white meat consumption and all-cause, CVD and IHD mortality: a meta-analysis of cohort studies [observational study with HR < 2; very weak evidence]

Current Atherosclerosis Report 2013: Unprocessed red and processed meats and risk of coronary artery disease and type 2 diabetes – An updated review of the evidence [observational study with HR < 2; very weak evidence]

Journal of the American Heart Association 2017. Role of total, red, processed, and white meat consumption in stroke incidence and mortality: A systematic review and meta‐analysis of prospective cohort studies [observational study with HR < 2; very weak evidence]

BMJ: Risks of ischaemic heart disease and stroke in meat eaters, fish eaters, and vegetarians over 18 years of follow-up: results from the prospective EPIC-Oxford study [observational study; weak evidence]

Other studies show a link with processed meat but not minimally processed red meat.

Circulation 2010: Red and processed meat consumption and risk of incident coronary heart disease, stroke, and diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis [observational study with HR < 2; very weak evidence] ↩

An extensive review found evidence for an increased risk of heart disease and all-cause mortality, albeit extremely small with a hazard ratio of 1.03.

JAMA Internal Medicine 2020: Associations of processed meat, unprocessed red meat, poultry, or fish intake with incident cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality [nutritional cohort study with HR<2; very weak evidence] ↩

International Journal of Sports Nutrition and Exercise Metabolism 2006: A review of issues of dietary protein intake in humans [overview article; ungraded]

↩International Journal of Sports Nutrition and Exercise Metabolism 2006: A review of issues of dietary protein intake in humans [overview article; ungraded] ↩

Institute of Medicine of the National Academies 2005: Dietary Reference Intakes for energy, carbohydrate, fiber, fat, fatty acids, cholesterol, protein, and amino acids [overview article; ungraded]

Journal of the American Dietetic Association 2002: Dietary reference intakes for energy, carbohydrate, fiber, fat, fatty acids, cholesterol, protein and amino acids [overview article; ungraded]

↩For instance, the data are clear that protein intake higher than the RDA is important for preventing sarcopenia and frailty as we age.

Nutrients 2016: Protein consumption and the elderly: What is the optimal level of intake? [overview article; ungraded]

American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2015: Protein and healthy aging [overview article; ungraded]

In addition, the RDA is well below what humans evolved eating. Although it is difficult to know what our hunter-gatherer ancestors ate, some scholars estimate they got at least 20-35% of their calories from protein. That equates to 100-175 protein grams per day for a 2,000-calorie intake or up to 260 grams for a 3,000 calorie intake. This total daily protein amount is two to four times greater than the proposed RDA.

NEJM 1985: Paleolithic nutrition. A consideration of its nature and current implications [overview article; ungraded]

American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2000: Plant-animal subsistence ratios and macronutrient energy estimations in worldwide hunter-gatherer diets [overview article; ungraded] ↩

“Reference body weight” is a rough approximation of your lean body mass – the part that needs protein. You can look up your reference body weight here or use the simple chart below to estimate your protein needs. ↩

The first study reports improved body composition and weight loss with no reduction in fat-free mass or resting energy expenditure on a high-protein diet in overweight women.

Nutrients 2018: Effects of adherence to a higher protein diet on weight loss, markers of health, and functional capacity in older women participating in a resistance-based exercise program [randomized trial; moderate evidence]

The following study, a 12-week intervention in obese women, also reports more significant fat mass loss with a 25% protein diet than a 15% protein diet.

British Journal of Nutrition 2020: The effect of 12 weeks of euenergetic high-protein diet in regulating appetite and body composition of women with normal-weight obesity: a randomised controlled trial [randomized trial; moderate evidence]

And the next two examples also report similar results:

International Journal of Obesity Related Metabolic Disorders 2004:

Effect of normal-fat diets, either medium or high in protein, on body weight in overweight subjects: a randomised 1-year trial[randomized trial; moderate evidence]Endocrine, Metabolic, and Immune Disorders of Drug Targets 2020:

Effects of a low carb diet and whey proteins on anthropometric, hematochemical, and cardiovascular parameters in subjects with obesity [nonrandomized study, weak evidence]One randomized trial and a large observational study report better bone health in those who ate more protein.

Journal of Bone and Mineral Research 2011: A real and volumetric bone mineral density and geometry at two levels of protein intake during caloric restriction: a randomized, controlled trial [moderate evidence]

Journal of Bone and Mineral Research 2000: Effect of dietary protein on bone loss in elderly men and women: the Framingham Osteoporosis Study [nutritional epidemiology study with HR<2; very weak evidence]

↩Protein and satiety

American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2008: Protein, weight management, and satiety [overview article; ungraded]

Increasing protein from 15% to 30% resulted in a significant caloric drop.

American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2005: A high-protein diet induces sustained reductions in appetite, ad libitum caloric intake, and body weight despite compensatory changes in diurnal plasma leptin and ghrelin concentrations [nonrandomized study, weak evidence]

↩The following reviews summarize the evidence for this nicely.

Nutrients 2016: Protein consumption and the elderly: what is the optimal level of intake? [overview article; ungraded]

American Journal of Clinical NUtrition 2015: Protein and healthy aging [overview article; ungraded]

The following observational study reports a high association between eating more protein and having less disability with aging.

Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 2019: Protein intake and disability trajectories in very old adults: the Newcastle 85+ study [observational study with HR>2, weak evidence]

Higher protein intake, especially when eating animal foods, is associated with greater muscle mass and the lowest functional decline risk.

Journal of Gerontology Biological Science and Medical Science 2017: High-protein foods and physical activity protect against age-related muscle loss and functional decline [nutritional epidemiology study; very weak evidence] ↩