Evidence based

Benefits of higher protein

You may have seen the new marketing in the grocery store. Every product now seems to be “a great source of protein.” Higher protein diets are in the news and all over social media.

With all the hype, you might be wondering, “What’s so special about protein?”

It’s not just hype. Protein really is important. Following the most current research, Diet Doctor has expanded its recommendations to include higher protein diets, along with varying degrees of carbohydrate reduction, as a healthy way to lose weight and improve many health conditions. Protein also plays a key role in higher satiety eating.

In this guide, you’ll learn why protein is so important. Protein plays two critical roles in good health you may not know about: protein regulates appetite for weight management and provides the building materials for strong bones.

Strong bones and a manageable appetite are important for everyone, but especially for individuals who are trying to lose weight or improve their health. Increasing your protein intake when you are trying to lose weight can ensure you maintain good health — and it can even make weight loss easier.

Did you know?

Protein is essential for bone health…

And you’re probably not

getting enough. Protein= ½ of bone volume

⅓ of bone mass

Did you know?

Protein is essential for bone health…

And you’re probably not

getting enough. Protein= ½ of bone volume

⅓ of bone mass

Key takeaways

Eat protein; lose weight: Protein can help you lose weight more effectively. Find out howNo bones about it: Did you know protein is great for bone health? Learn more about who needs more of it.

Tame your appetite: Protein plays an important role in reducing hunger and snacking. Get the two most important tips to help curb your cravings.

1. What does protein do?

The food we eat has two primary purposes:

- to provide us with energy to run our bodies and live our lives, and

- to create the structural and functional elements that make up our bodies.

The carbohydrates and fats in food provide most of our energy for the first purpose.

Protein is different. Protein is an inefficient energy source for the body.1 But it is essential for the body’s structure and function. These include obvious things — such as muscle tissue — and include less obvious components, such as enzymes, hormones, and bone.

Nearly half the protein in your body is skeletal muscle, and protein is the most important nutrient for maintaining and building it.2 Evidence indicates most people would improve their lean muscle mass by making sure they have adequate protein intake.3

For people who want to add muscle, getting enough protein is a must. Athletes who are breaking down and rebuilding muscle need more dietary protein to aid in this process.4 If you are interested in building muscle mass, check out Diet Doctor’s guide to improving your body composition for more on this topic.

Even if you’re not interested in building muscle, you’ll want to maintain the muscle you have for general good health. An important part of doing that is making sure you get enough protein.

How much protein do you need for good health?

How much protein you need depends on several factors, such as how tall you are or whether you are male or female. You can use this chart to estimate your daily protein requirements.

High-protein diet minimum daily targets

| Height | Women | Men |

|---|---|---|

| Under 5’4″ (<163 cm) | 90 grams | 105 grams |

| 5’4″ to 5’7″ (163 to 170 cm) | 100 grams | 110 grams |

| 5’8″ to 5’10” (171 to 178 cm) | 110 grams | 120 grams |

| 5’11” to 6’2″ (179 to 188 cm) | 120 grams | 130 grams |

| Over 6’2″ (>188 cm) | 130 grams | 140 grams |

Aim for approximately this much protein every day.

If you are older, very active, trying to lose weight, or have a metabolic condition, such as diabetes, you may want to increase your protein target by around 20 to 30 grams more per day.

2. Protein for better weight loss

Research shows a diet higher in protein leads to greater weight loss compared to one with lower protein levels.5

Protein has positive effects on two things important for weight loss:

- maintaining muscle and bone mass, and

- taming appetite.

Protein, muscle, and metabolism

Although weight loss can improve many aspects of health, it can have at least one detrimental effect. Weight loss, especially repeated cycles of weight loss, can lead to loss of muscle mass.6

Part of healthy weight loss is maintaining as much of your fat-free mass as possible while losing excess body fat. Your fat-free mass includes muscle and bone; both can be negatively impacted by weight loss.

Loss of muscle mass can not only lead to loss of bone mass, it can also lead to a slower metabolism. When you have a slower metabolism, your body burns fewer calories. So when you lose muscle mass, you need to eat even less in order to continue to burn body fat.7 In contrast, keeping your muscle mass during weight loss means you’ll use more energy than you would if muscle mass were reduced, even when you’re resting.8

3. Protein for better bone health

Although the relationship between protein and muscle seems clear, many people don’t know protein is also essential for bone health. This is true in general but is particularly critical during weight loss and especially important for older adults.

Women, especially older women, are at particular risk of bone loss. But men also suffer from bone loss and are at higher risk of dying after a bone fracture takes place.9

We’ve all heard calcium and vitamin D are important for maintaining strong bones. Many tasty supplements on the market provide these nutrients, and people at risk for osteoporosis may take them faithfully. But the US Preventive Services task force found little evidence these supplements prevented fractures, which is the primary goal of improving bone health.

The role of protein in bone health is less well known, but just as — or even more — important. Protein supplies the amino acids needed to make the collagen that makes up the bone matrix. It is estimated that protein makes up about 50% of the volume of bone and about one-third of its mass.10

No randomized controlled trials have been done looking at the effects of protein intake on preventing bone fractures. However, an important marker of bone strength — bone mineral density — is linked to increased dietary protein.11

Older adults and bone health

Older adults in particular may need more protein to support good health, promote recovery from illness, and maintain functionality, particularly when it comes to maintaining strong bones.12

In the past, experts thought increased protein could harm bones because higher protein diets seemed to result in higher calcium levels in the participants’ urine. But with more advanced techniques, researchers found dietary protein helps increase absorption of dietary calcium, so there is more calcium available for bone-building and more left to be excreted.13

So far, no quality evidence has been found to indicate increased protein damages bones.14 On the contrary, older adults, who are at the greatest risk for bone loss, need to make sure they get enough protein.

Older adults tend to eat fewer calories overall, and this can mean they also eat less protein. Older women, especially, may not meet even the low intake levels of the Recommended Daily Allowance (RDA).15

The RDA for protein is 0.8 grams per kilo of reference body weight.16 But, as we explain in this guide to higher protein diets, this amount is likely too low for most people who want to improve their health.

Because older adults do not metabolize protein as well as younger people, researchers believe if you are over 65 years of age, you need a protein intake at least 35% higher than what the RDA recommends to preserve lean body mass and maintain bone health.17

These higher targets translate to an intake of at least 1.0 gram per kilo of reference body weight. At Diet Doctor, we recommend slightly higher intakes for promoting overall good health, especially during weight loss. See the simple chart above to find out how much protein you should aim for on most days.

Weight loss and bone health

In the past, experts thought obesity would protect bone health. The tension skeletal muscles put on the bones they are attached to helps stimulate bone growth. More bodyweight often means more muscle, which usually means stronger bones.

But this is not the whole picture.

If muscle mass has been reduced — maybe by multiple rounds of weight loss, especially with very low-calorie restriction — a person who is overweight or obese may also have a condition called sarcopenic obesity, which is having both low muscle mass and obesity.18

Additionally, the hormonal and inflammatory aspects of obesity can undermine bone health.19 Both obesity and calorie-restricted diets for weight loss are associated with an increased risk of fracture.20

This seems to create an impossible bind. If both losing weight and being overweight are bad for bone health, what can you do? The answer may be a higher protein diet for weight loss.

Ensuring you get plenty of protein may help protect your bones during weight loss.21 Adding weight-bearing exercise to the mix makes it even more likely you’ll reduce the bone loss that can occur while dieting.22

However, higher protein diets can help with weight loss in other ways, besides just protecting bone health. The effects of protein on appetite are also important for taming the hunger that can derail any diet.

4. Protein and appetite

Different people may find different types of food filling. However, research shows, calorie for calorie, protein foods — along with high-fiber vegetables — are the best foods for helping your body feel full.23

Since hunger is a primary reason people are unable to stick to diets, a dietary approach that reduces hunger may lead to increased weight loss and long-term success.24 In fact, getting adequate protein may be built into the human body in a way that makes it difficult to maintain a healthy weight if protein intake is too low.

Protein leverage hypothesis

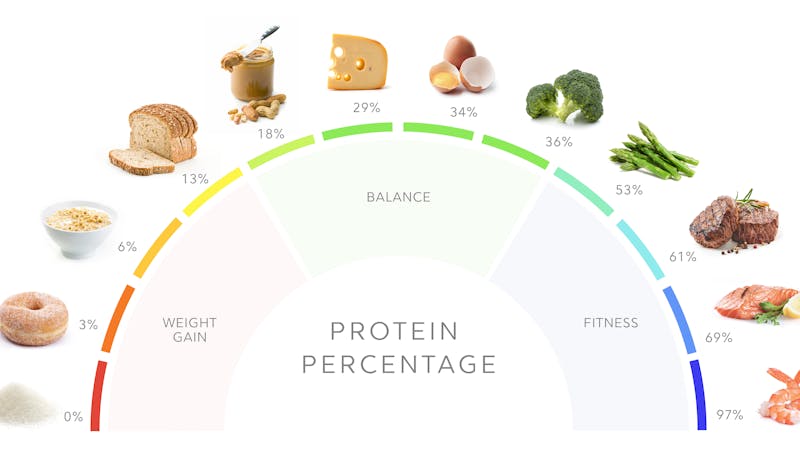

A concept called the protein leverage hypothesis argues all creatures, from insects to humans, are driven to eat until they fulfill their need for protein.25 This isn’t a problem if the available food sources have a high protein percentage, which means a high amount of protein per calorie.

When you choose foods with a high protein percentage, you are more likely to eat fewer calories than you would otherwise. Your protein needs will be met quickly, without having to take in a lot of calories from fat or carbohydrate. Foods with a high protein percentage are things like fish and seafood, chicken breast, and lean meats.

Choosing these foods means getting the most protein with the fewest calories.

But the reverse is true as well.

If you choose foods with a low amount of protein per calorie, you might be much more likely to continue to eat until your protein needs are met. Foods like pasta, cereal, or bread have low amounts of protein per calorie compared to foods like meat and eggs.

A diet made up mostly of foods with a low protein percentage may result in either not enough protein or too many calories. Not enough protein can lead to loss of muscle and bone. Too many calories can lead to weight gain.26

Choosing foods with a high protein percentage helps you reach your protein goals without eating too many calories, which can help with weight loss.

But, the implications of the protein leverage theory go beyond a focus on higher protein foods for weight loss. The theory also gives us a different perspective on willpower and what it takes to lose weight.

5. Protein, willpower, and self-blame

Clinicians who work with people trying to lose weight sometimes encounter patients who feel as if they just can’t stop eating. This can happen on many kinds of diets. Despite following their diet all day, in the evening, the ice cream in the freezer calls to them irresistibly.

At some point in our lives, many of us have felt an urge to eat even when we “know” we’ve had plenty of calories for the day. We may attribute this urge to a “craving” or “lack of willpower.”

But could it be a lack of protein instead?

The protein leverage theory suggests — and research, along with clinical experience, confirms — increasing protein intake at the first meal of the day, whenever that occurs, can stop evening cravings and urges to eat, without having to call on “willpower.”

Researchers have found most Americans eat sufficient protein at lunch and more than enough at dinner, with most people eating very low protein at breakfast — or none at all.27 This pattern alone could be an indication of protein leverage at work, as the body tries to meet its protein needs before the overnight fast.

Several studies show when participants are given a high-protein meal at the start of their day, cravings, snacking, and overall energy intake go down.

For example, when study participants consumed eggs for breakfast, rather than a bagel with the same number of calories but lower in protein, they ate fewer calories over the course of the day, without any other modification to their diet.28

Other studies indicate, in a population of young overweight or obese women, a higher protein breakfast leads to increased fullness, reduced appetite, and fewer cravings compared to skipping breakfast. The participants who ate a higher-protein breakfast snacked less on high-fat and high-sugar treats in the evenings.29

No matter when your “breakfast” is — early morning or in the afternoon — the evidence suggests it is important to do two things:

- Make sure your “first meal” of the day has at least 25 grams of protein.

- Get sufficient protein during the day to meet your protein needs.

Depending on your health goals, you may want to meet your protein needs with lower calorie foods or with higher fat foods. But if you are trying to lose weight, plenty of protein with just enough calories may be the ticket to success.

Decreasing protein percentage and rise in obesity

Our bodies are driven to get sufficient protein. But, we’ve been told it is “healthier” to eat foods — pasta, rice, and bread — with a low protein percentage. And we’ve been told to limit or avoid foods — eggs and meat — with a higher protein percentage.

During the rising rates of obesity of the past four decades, calories in the food supply have increased, yet the percentage of calories from protein has decreased.30

Because both calorie and carbohydrate intake went up in the past 40 years, it’s been difficult to tease apart which one might be the reason for increased rates of obesity.

But perhaps we could think about this differently: Maybe it’s not so much what we were eating, but what we weren’t eating that has led to this worldwide weight gain. Maybe focusing on meeting protein needs is the key to preventing overweight and obesity in the first place.

6. Why protein is important

Protein is not like carbohydrates and fats, which are primarily just sources of energy. Protein is necessary for the body to function. It is also necessary for building the structures that make up the body, such as bone and muscle.

If you are an older adult, you need to pay special attention to protein intake. Older adults, especially women, need more protein — to preserve bone and muscle — but tend to eat less of it.

Protein is also important during weight loss, again to preserve bone and muscle. Maintaining muscle mass keeps your metabolism burning energy, making weight loss more effective and easier to maintain.

Finally, protein helps you manage your appetite and your cravings. You can give your “willpower” a boost by ensuring you get adequate protein every day, starting with your first meal.

Benefits of higher protein - the evidence

This guide is written by Adele Hite, RD and was last updated on June 19, 2025. It was medically reviewed by Dr. Bret Scher, MD on September 25, 2022.

The guide contains scientific references. You can find these in the notes throughout the text, and click the links to read the peer-reviewed scientific papers. When appropriate we include a grading of the strength of the evidence, with a link to our policy on this. Our evidence-based guides are updated at least once per year to reflect and reference the latest science on the topic.

All our evidence-based health guides are written or reviewed by medical doctors who are experts on the topic. To stay unbiased we show no ads, sell no physical products, and take no money from the industry. We're fully funded by the people, via an optional membership. Most information at Diet Doctor is free forever.

Read more about our policies and work with evidence-based guides, nutritional controversies, our editorial team, and our medical review board.

Should you find any inaccuracy in this guide, please email andreas@dietdoctor.com.

Institute of Medicine of the National Academies 2005: Dietary Reference Intakes for energy, carbohydrate, fiber, fat, fatty acids, cholesterol, protein, and amino acids [overview article; ungraded]

↩Institute of Medicine of the National Academies 2005: Dietary Reference Intakes for energy, carbohydrate, fiber, fat, fatty acids, cholesterol, protein, and amino acids [overview article; ungraded]

↩A meta-analysis of RCTs demonstrates eating more protein leads to better muscle gains.

Journal of Nutrition 2020 The role of protein intake and its timing on body composition and muscle function in healthy adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials

[strong evidence]Observational studies show those who eat more protein have greater muscle mass.

American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2016: Relation between mealtime distribution of protein intake and lean mass loss in free-living older adults of the NuAge study

[nutritional epidemiology study with HR<2, very weak evidence]American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2008: Dietary protein intake is associated with lean mass change in older, community-dwelling adults: the Health, Aging, and Body Composition (Health ABC) Study

[nutritional epidemiology study with HR<2, very weak evidence]British Journal of Nutrition 2016: Dietary protein intake is associated with better physical function and muscle strength among elderly women [nutritional epidemiology study with HR<2, very weak evidence]

↩Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition 2017: International Society of Sports Nutrition Position Stand: protein and exercise [overview article; ungraded]

American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2003: Effect of a high-protein, energy-restricted diet on body composition, glycemic control, and lipid concentrations in overweight and obese hyperinsulinemic men and women [randomized trial; moderate evidence]

Nutrients 2019: Pretreatment fasting glucose and insulin as determinants of weight loss on diets varying in macronutrients and dietary fibers-the POUNDS LOST study [randomized trial; moderate evidence]

International Journal of Obesity 2015: The role of higher protein diets in weight control and obesity-related comorbidities [overview article; ungraded]

↩One study shows individuals who have lost and regained weight more than five times in their lifetime are six times more likely to develop sarcopenia — a loss of muscle mass — compared to those without any cycles of weight gain and loss.

Obesity (Silver Spring) 2019: Weight cycling as a risk factor for low muscle mass and strength in a population of males and females with obesity [non-controlled study; weak evidence]

Individuals with both obesity and sarcopenia — a loss of muscle mass — are at a greater risk of frailty, disability, and early mortality.

Clinical Nutrition 2018: Sarcopenic obesity: time to meet the challenge [overview article; ungraded]

↩Sports Medicine 1996: The importance of fat free mass maintenance in weight loss programmes [overview article; ungraded]

American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 1991: Body composition as a determinant of energy expenditure: a synthetic review and a proposed general prediction equation [overview article; ungraded]

In the US, over half the population over age 50 is affected by osteoporosis, a condition where bone mass is lost and the risk of breaking a bone increases dramatically. One out of three American women will suffer a fracture compared to one out of five men, but men are more likely to die as a result.

Annual Review of Nutrition 2012: Bone metabolism in obesity and weight loss [overview article; ungraded]

↩International Congress Series 2007: Effects of protein on the calcium economy [overview article; ungraded]

↩Osteoporosis International 2018: Benefits and safety of dietary protein for bone health — an expert consensus paper endorsed by the European Society for Clinical and Economical Aspects of Osteoporosis, Osteoarthritis, and Musculoskeletal Diseases and by the International Osteoporosis Foundation [overview article; ungraded]

↩Joint Bone Spine 2001: Protein intake and bone disorders in the elderly [overview article; ungraded]

The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 2005: The impact of dietary protein on calcium absorption and kinetic measures of bone turnover in women [randomized trial; moderate evidence]

↩Journal of the American College of Nutrition: 2005: Dietary protein: an essential nutrient for bone health [overview article; ungraded]

↩Nutrition Today 2019: Optimizing dietary protein for lifelong bone health

a paradox unraveled [overview article; ungraded]The RDA level is set by the US Institutes of Medicine to prevent malnutrition. It does not address protein needs for good health or the prevention of disease.

Applied physiology, nutrition, and metabolism 2016: Protein “requirements” beyond the RDA: implications for optimizing health [overview article; ungraded]

The RDA is defined as the “average daily level of intake sufficient to meet the nutrient requirements of nearly all (97%-98%) healthy people.”

↩“Reference body weight” is a rough approximation of your lean body mass – the part that needs protein. You can look up your reference bodyweight here or use the simple chart above to estimate your protein needs. ↩

Journal of Nutrition 2015: Dietary protein requirement of men >65 years determined by the indicator amino acid oxidation technique is higher than current estimated average requirements [non-controlled study; weak evidence]

The Journal of Nutrition 2015: Dietary protein requirement of female adults >65 years determined by the indicator amino acid oxidation technique is higher than current recommendations [non-controlled study; weak evidence]

The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 2014: Association between lean mass, fat mass, and bone mineral density: a meta-analysis [systematic review of randomized trials; strong evidence]

Annual Review of Nutrition 2012: Bone metabolism in obesity and weight loss [overview article; ungraded]

Obesity (Silver Spring) 2019: Weight cycling as a risk factor for low muscle mass and strength in a population of males and females with obesity [non-controlled study; weak evidence]

Nutrition Research 2017: Obesity is a concern for bone health with aging [overview article; ungraded]

↩Annual Review of Nutrition 2012: Bone metabolism in obesity and weight loss [overview article; ungraded]

↩Journal of Bone and Mineral Research 2011: Areal and volumetric bone mineral density and geometry at two levels of protein intake during caloric restriction: a randomized, controlled trial [randomized trial; moderate evidence]

Nutrition Journal 2017: Effect of a high protein diet and/or resistance exercise on the preservation of fat free mass during weight loss in overweight and obese older adults: a randomized controlled trial [randomized trial; moderate evidence]

European Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2018: Dietary fat, fibre, satiation, and satiety—a systematic review of acute studies [systematic review of randomized trials; strong evidence]

American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2008: Protein, weight management, and satiety [overview article; ungraded]

↩Journal of the American Dietetic Association 2005: Perceived hunger is lower and weight loss is greater in overweight premenopausal women consuming a low-carbohydrate/high-protein vs high-carbohydrate/low-fat diet [randomized controlled trial; moderate evidence] ↩

Obesity Reviews 2005: Obesity: the protein leverage hypothesis [overview article; ungraded]

PLoS One 2011: Testing protein leverage in lean humans: a randomised controlled experimental study

↩

[randomized trial; moderate evidence]Obesity 2019: The Potential Role of Protein Leverage in the US Obesity Epidemic

[overview article; ungraded] ↩Applied physiology, nutrition, and metabolism 2016: Protein “requirements” beyond the RDA: implications for optimizing health [overview article; ungraded]

Nutrition Research 2010: Consuming eggs for breakfast influences plasma glucose and ghrelin, while reducing energy intake during the next 24 hours in adult men [randomized trial; moderate evidence]

Journal of the American College of Nutrition 2005: Short-term effect of eggs on satiety in overweight and obese subjects [randomized trial; moderate evidence]

American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2013: Beneficial effects of a higher-protein breakfast on the appetitive, hormonal, and neural signals controlling energy intake regulation in overweight/obese, “breakfast-skipping,” late-adolescent girls [randomized trial; moderate evidence]

Nutrition Journal 2014: A randomized crossover, pilot study examining the effects of a normal protein vs. high protein breakfast on food cravings and reward signals in overweight/obese “breakfast skipping”, late-adolescent girls [randomized trial; moderate evidence]

American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2011: Trends in carbohydrate, fat, and protein intakes and association with energy intake in normal-weight, overweight, and obese individuals: 1971-2006 [non-controlled study; weak evidence] ↩