Plant protein vs. animal protein: Which one is healthier for you?

Increasing your protein intake can provide many health benefits, including weight loss, better body composition, improved blood sugar control, and higher satiety, to name a few.

However, not all protein sources are the same. Animal and plant proteins differ significantly in many ways. Does it matter whether or not you choose animal- or plant-based proteins? In this guide, we will explore that question and the latest available data.

As with all of our guides, Diet Doctor wants to equip you with science-based information and suggestions and then empower you to make your own informed decisions. If you follow our tips and suggestions in this guide, we believe that you will have no trouble meeting your protein needs with either animal or plant proteins, or even a mix of both, depending on your lifestyle.

Summary

- Increasing your protein intake, whether through animal or plant sources, can provide many health benefits.

- Gram for gram, animal protein sources are more complete, have better absorption and muscle-building effects, have more additional nutrients, and contain fewer calories and carbohydrates.

- You can meet all of your protein needs with plant-only sources if you choose soy or if you mix and match your plant sources to get a full amino acid profile.

- No high-quality data exist to support the concern that eating more animal products comes with adverse health effects. If you are leading an otherwise healthy lifestyle, you should be able to enjoy your favorite protein sources.

What is a complete protein?

You may have heard various foods categorized as a “complete protein” or an “incomplete protein.” What exactly does that mean?After you eat protein-containing foods, your body breaks down the protein into amino acids – the “building blocks” of protein. Of the 20 amino acids found in protein, your body can make 11 of them. The other nine are essential, meaning that they must come from your diet because your body can’t produce them.

Fortunately, protein from animals is “complete,” providing all of the essential amino acids in amounts that your body needs. However, plant proteins (with the exception of soy) are “incomplete” because they lack sufficient amounts of one or more essential amino acids.1

That doesn’t mean you can’t meet your protein needs from plants. You simply have to mix and match to make up for the amino acids that are in short supply. For example, you can pair legumes, such as beans or peas (which are high in the amino acid lysine but low in methionine), with grains that are high in methionine but low in lysine. Barley and lentil soup is a popular example of this pairing.

Alternatively, you can combine beans with nuts and seeds, have hummus with whole grain pita, or make the classic rice with beans combination.

Carb-heavy combinations like these aren’t a good fit for a low-carb diet, but if you are less strict with carb intake, they can provide all of the essential amino acids.

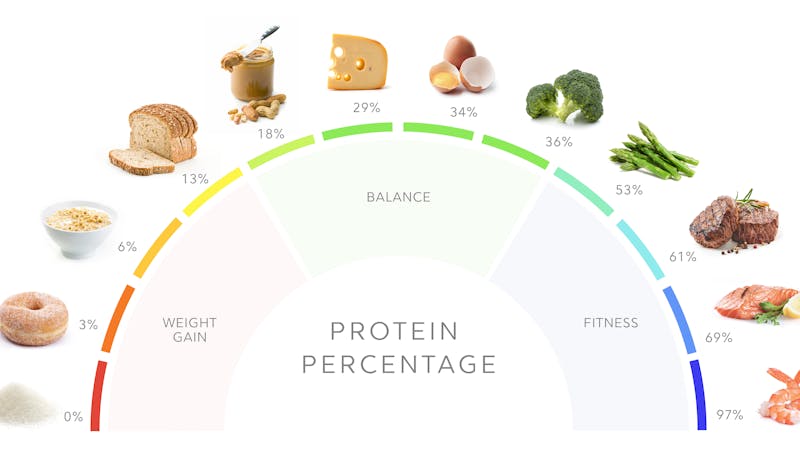

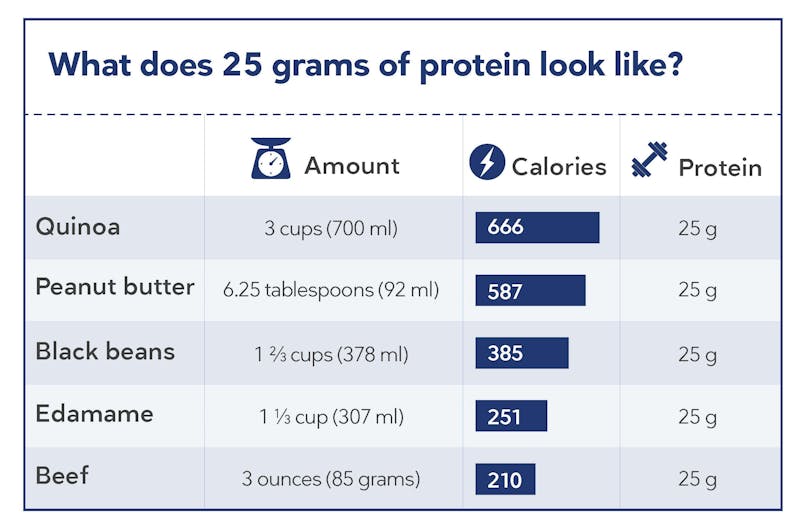

Carb and calorie content

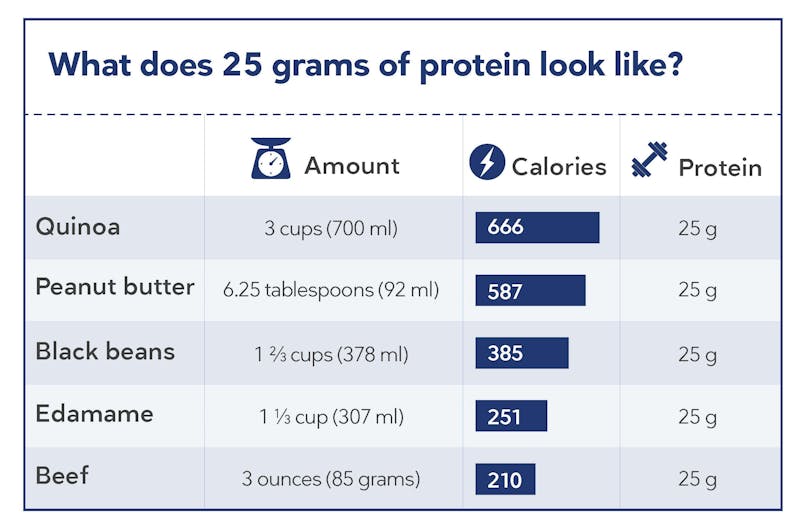

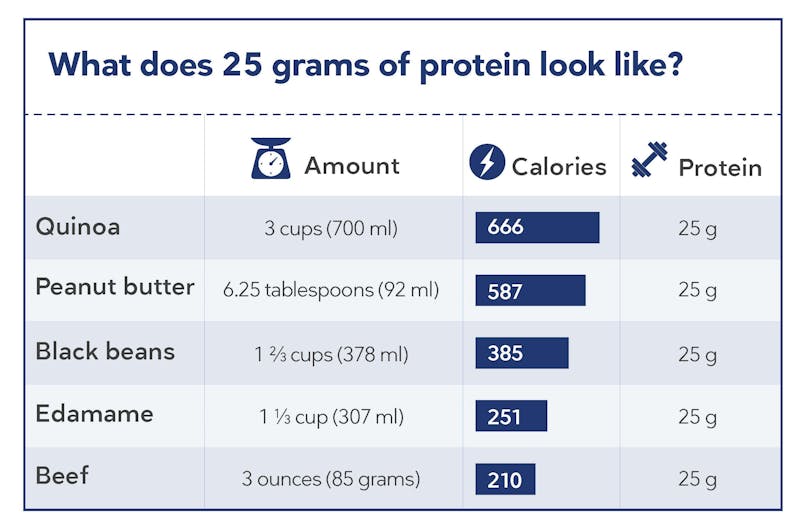

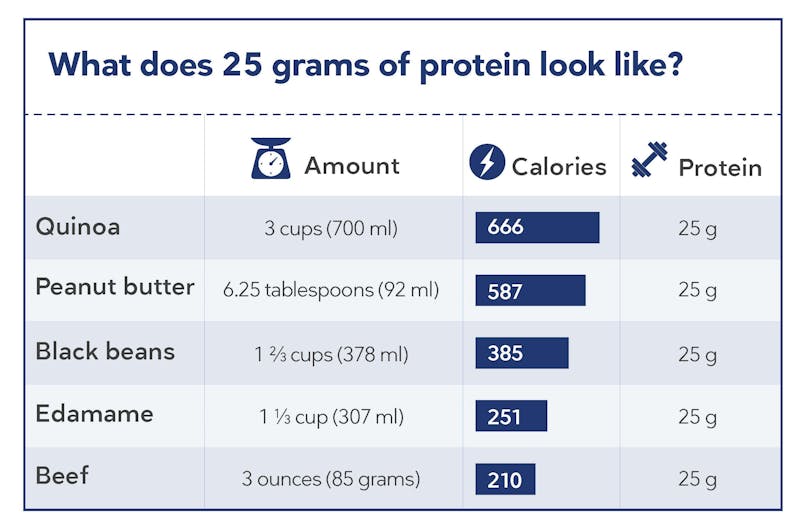

Plant sources of protein tend to be higher in carbohydrates and calories than the equivalent amount of protein from animal sources. If you follow a very low-carb or keto diet, you may find it challenging to meet your dietary goals if you use plants as your only source of protein.Our protein table shows the number of calories required to obtain 25 grams of protein. As you can see, you can eat 25 grams of protein from beef at a fraction of the calories that you would get from quinoa, peanut butter, or black beans if you ate enough of each to get 25 grams of protein.

Your serving of beef also has zero carbs, whereas your quinoa comes with 126 grams and black beans with 68 grams.

If you want to keep your net carb intake below 20 or 50 grams per day and keep your calorie content as low as possible, plant sources may not be a realistic option. However, if your carb and calorie intake are more liberal, then plant sources may be a good choice.

Bioavailability/absorption

On average, your body absorbs animal-based protein better than plant-based protein. Soy is once again the exception and is equivalent to animal sources.The practical implication is that you may need to eat 20-50% more plant proteins to absorb the equivalent amount of amino acids as you would from animal sources.2

That doesn’t mean you can’t meet your goals with mostly plant proteins. You absolutely can, particularly if you prioritize soy intake. However, you need to watch the associated carbs and calories that come with the higher-required volume of food if you are trying to lose weight.

Anabolic or muscle-building benefits

That doesn’t mean, however, that eating protein will automatically give you the physique of a bodybuilder. It does mean that eating more protein can help build or maintain your existing muscle mass — especially if you exercise.

On average, animal protein sources have greater gram-for-gram muscle-building benefits than plant proteins. 4

Soy may once again be unique among plant proteins as it appears to have similar muscle-building effects to animal proteins.5

If you are looking for the maximum muscle-building effect per gram of protein and per calorie, animal sources appear to be the best choice.6

With non-soy plant proteins, you’ll need to combine multiple types of plants and consume more protein for the equivalent muscle-building effect you’d get from animal protein.7 However, this latter approach is certainly doable for those who do not consume animal products.

Associated nutrients

Animal- and plant-based proteins each have certain benefits over the other with regard to nutrients.One theory regarding the “protein leverage hypothesis” is that our craving for whole-food protein has as much to do with the micronutrients as it does with the protein itself.8

Compared with plant protein sources, animal sources are higher in vitamin B12, vitamin D, the omega 3 fatty acid DHA, heme-iron, zinc, and vitamin K2.9

Compared with animal protein sources, plant sources are higher in fiber, vitamin C, and flavonoids.10

While there is no such thing as a medical fiber deficiency, some people may want to add high-fiber foods, such as above-ground vegetables, to their diet if most of their protein comes from animals.11

Learn more in our guide 15 high-fiber foods that are low in carbs.

However, if most of your protein comes from plants, we strongly suggest that you consider supplementing with the vitamins and minerals listed above.12

Learn more in our guides on following a vegan or vegetarian low-carb diet.

Longevity and chronic disease

One of the most-discussed concerns about protein, in general, is the effect it has on human longevity. Data from flies, rats, and other animals suggest that lower-protein diets can improve longevity, while human data are sparse and very weak.13In theory, eating higher amounts of protein can “turn on” growth signals in our body, most notably mTOR (mechanistic target of rapamycin).14

But do the data from mice and flies equally apply to humans? Maybe not.

As we have shown in this guide, eating more protein can help with weight loss, metabolic health, and gaining strength — all of which are important for improving health and living well.

Furthermore, animal data show that lower-protein diets can improve longevity, but also lead to obesity.15 And higher protein diets improve reproductive health, which for flies and mice may be the ultimate marker of overall health.16

The animal data, therefore, appear to suggest that we need to choose between health and longevity, an interesting paradox.

Further, we must also recognize that the exact impact of animal protein on longevity is not only unclear, but it may be extremely small if the impact exists.17

In other words, would avoiding meat help you to live longer by months? Years? A decade or longer? The answer remains unclear, but given the low hazard ratios for all-cause mortality in human studies of animal vs plant protein, we can infer that most individuals will not see a meaningful increase in lifespan.

In light of the need to consume adequate protein to prevent loss of muscle tissue and frailty as we age, restricting protein in order to increase lifespan seems inadvisable.

You can read more below for a representative example of a human study suggesting lower animal or overall protein intake improves longevity, and see why we feel the quality of the research does not support the recommendation.

When it comes to possible differential effects of plant vs animal sources of protein on chronic diseases, some data suggest that animal-source proteins are more concerning. That said, the data proposing that animal protein intake leads to diabetes, heart disease, or even premature death is low-quality and, we believe, should not be used to make conclusive arguments.21

As we cover in our detailed guides on red meat and another on diet and cancer, the data against animal foods remain very weak. When looking at higher-quality evidence, we find no high quality evidence to support the claim that animal food sources are less healthy than plant-based sources, especially within the context of an otherwise healthy lifestyle.

Environment

It is true that cows and other ruminant animals emit methane when they burp, and may have a greater greenhouse gas contribution than other animals like chickens or pigs. However, calculating the contribution of this methane to greenhouse-gas emissions remains complicated.

To start with, there is a vast difference in the environmental impact of industrial cattle feeding operations and grass-finished cattle ranches. As we discuss in our podcast with dietician, farmer, and regenerative agriculture advocate Diana Rodgers, grazing cattle can benefit the environment by improving soil quality and removing carbon from the atmosphere.

The environmental argument is also nuanced when examining how much water and other resources cows require. The water used for meat is derived mostly from rainfall, not irrigation. Rice and almonds, however, require much more “blue water —” the limited-resource water derived from irrigation – per gram of protein than does meat.22

Ultimately, when zooming out and looking at environmental damage through a wider lens, human activities and fossil fuel use contribute far more to climate change than do ruminant animals.23 And this includes the fossil fuels required for plant-based agriculture.

The full environmental question is far too complex to explore adequately in this guide. However, the details surrounding this topic are more nuanced than the standard narrative suggests.

If you would like to learn more about this important issue and how you can make a difference, please listen to our podcasts with greenhouse gas expert Professor Frank Mitloehner and another with environmental lawyer and rancher Nicolette Hahn Niman. You can also read our three-part series on the green keto meat eater.

Animals or plants, it’s your choice

Increasing your protein intake, whether through animal or plant sources, can provide many health benefits.Gram for gram, animal protein sources are more complete, have better absorption and muscle-building effects, have more additional nutrients, and contain fewer calories and carbohydrates.

No high-quality data exist to support the concern that eating more animal products comes with adverse health effects.

Despite the differences between animal and plant protein sources, you can still meet all of your protein needs with plant-only sources.

If you are on a plant-only diet, be sure to mix and match your plant sources to get a full amino acid profile, and aim for at least 1.5 grams per kilo of body weight to absorb enough functional protein. Remember that eating soy is a great way to get a complete protein that has good absorption. Please also talk to your healthcare provider about necessary vitamin and mineral supplementation.

Whether you prefer plant- or animal-based protein sources, here are some of our favorite recipes that you can enjoy.

High-protein recipes

Learn more about protein

Plant protein vs. animal protein: Which one is healthier for you? - the evidence

This guide is written by Dr. Bret Scher, MD and was last updated on June 19, 2025. It was medically reviewed by Dr. Michael Tamber, MD on July 28, 2022.

The guide contains scientific references. You can find these in the notes throughout the text, and click the links to read the peer-reviewed scientific papers. When appropriate we include a grading of the strength of the evidence, with a link to our policy on this. Our evidence-based guides are updated at least once per year to reflect and reference the latest science on the topic.

All our evidence-based health guides are written or reviewed by medical doctors who are experts on the topic. To stay unbiased we show no ads, sell no physical products, and take no money from the industry. We're fully funded by the people, via an optional membership. Most information at Diet Doctor is free forever.

Read more about our policies and work with evidence-based guides, nutritional controversies, our editorial team, and our medical review board.

Should you find any inaccuracy in this guide, please email andreas@dietdoctor.com.

Amino Acids 2018: Protein content and amino acid composition of commercially available plant-based protein isolates [laboratory study; ungraded]

Food and Agriculture Organization of The United Nations 2011: Dietary protein quality evaluation in human nutrition [overview article; ungraded] ↩

The following summaries document the greater bioavailability and essential amino acid content of animal proteins:

Food and Agriculture Organization of The United Nations 2011: Dietary protein quality evaluation in human nutrition [overview article; ungraded]

Nutrients 2019:

The role of the anabolic properties of plant- versus animal-based protein sources in supporting muscle mass maintenance: A critical review [overview article; ungraded]The Journal of Nutrition 2015: The skeletal muscle anabolic response to plant- versus animal-based protein consumption

[overview article; ungraded] ↩Nutrition Reviews 2016:

Effects of dietary protein intake on body composition changes after weight loss in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis [systematic review of randomized trials; strong evidence]American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2012: Effects of energy-restricted high-protein, low-fat compared with standard-protein, low-fat diets: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials [systematic review of randomized trials; strong evidence]

Nutrients 2019: Dietary protein and muscle mass: Translating science to application and health benefit [overview article; ungraded] ↩

The following reviews highlight how animal protein has more anabolic (or muscle-building) effects than plant-based protein, concluding: “For example, proteins found in milk, whey, egg, casein, and beef have the highest score (1.0), while scores for plant-based proteins are as follows: soy (0.91), pea (0.67), oat (0.57), and whole wheat (0.45).”

Proceedings of the Nutrition Society 2018: Characterising the muscle anabolic potential of dairy, meat and plant-based protein sources in older adults [overview article; ungraded]

Journal of Nutrition 2015: The skeletal muscle anabolic response to plant – versus animal-based protein consumption [overview article; ungraded]

↩The following randomized trial shows similar anabolic effects for soy and whey protein supplements

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2020: No significant differences in muscle growth and strength development when consuming soy and whey protein supplements matched for leucine following a 12 week resistance training program in men and women: A randomized trial [ moderate evidence]

↩As we mentioned previously, soy may be the exception, with some evidence suggesting it has similar muscle-building effect as animal based protein. ↩

Remember, plant protein is not as bioavailable as animal protein, so you need to consume about 20-50% more to get the same effect. ↩

Obesity reviews 2005: Obesity: the protein leverage hypothesis [overview article; ungraded]

PLoS One 2011: Testing protein leverage in lean humans: a randomised controlled experimental study [randomized trial; moderate evidence] ↩

Experimental Biology and Medicine 2007: Vitamin B12 sources and bioavailability

[overview article; ungraded]American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2004: Vitamin D fortification in the United States and Canada: current status and data needs

[overview article; ungraded]International Journal of Vitamin and Nutrition Research 1998: Can adults adequately convert alpha-linolenic acid (18:3n-3) to eicosapentaenoic acid (20:5n-3) and docosahexaenoic acid (22:6n-3)? [overview article; ungraded]

Biological Trace Element Research 2009: Total iron and heme iron content and their distribution in beef meat and viscera [overview article; ungraded]

Nutrients 2020: Vitamin K2 needs an RDI separate from vitamin K1 [overview article; ungraded]

↩Although there is no essential requirement for fiber intake, many observational studies associate higher fiber intake with numerous potential health benefits.

Nutrients 2020:

The health benefits of dietary fibre [overview article; ungraded]The US Food and Nutrition Board recommends a minimum daily fiber intake of 25 grams for women and 38 grams per day for men, based on research connecting higher fiber intake with better health.

Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics: Position of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics: Health implications of dietary fiber [overview article; ungraded]

However, these recommendations are based mostly on observational studies in populations eating mixed diets or low-fat diets. We do not have specific information for those following low-carb diets.

High fiber intake versus low fiber intake could serve as a proxy for food quality in many studies. Carbohydrate-containing foods that are low in fiber tend to be lower quality, highly processed foods. Therefore, some experts postulate that people who eat low-carb diets may not receive the same benefits from fiber as those who eat higher-carb diets. However, more data are needed to support this claim.

Vitamin C can act as an antioxidant and also plays a role in many enzymatic reactions, It is much more plentiful in plant foods and rarely found in animal foods.

Advances in Nutrition 2014: Vitamin C [overview article; ungraded]

Flavonoids are believed to have antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and even anticancer properties. They are found almost exclusively in plant foods. However there is no absolute requirement for flavonoids, and no known harm of flavonoid deficiency.

Journal ofNutritional Science 2016: Flavonoids: an overview [overview article; ungraded]

↩Although most of the data are from lower quality observational studies, increased fiber intake is often associated with improved health outcomes. This could be due to associations with insulin sensitivity, reduced Apo B containing lipid particles, beneficial microbiome effects, and other potential mechanisms.

Nutrients 2020:

The Health Benefits of Dietary Fibre[overview article; ungraded] ↩Any decision to start, stop, or adjust supplements and medications should be made in conjunction with your healthcare provider ↩

EBioMedicine 2019: The impact of dietary protein intake on longevity and metabolic health [overview article; ungraded] ↩

Nature Cell Biology 2019: mTOR as a central hub of nutrient signalling and cell growth [overview article; ungraded]

Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology 2013: Amino acid signalling upstream of mTOR [overview article; ungraded]

The concern is that continuous growth signaling encourages the growth of not only healthy cells but also diseased or cancerous cells. Therefore, all other things being equal, one might want to limit continuous mTOR stimulation by lowering protein intake.

Nature 2009: Rapamycin fed late in life extends lifespan in genetically heterogeneous mice [animal study; very weak evidence] ↩Nutrition Research Review 1997:

Integrative models of nutrient balancing: application to insects and vertebrates [review of animal studies, very weak evidence]The Royal Society Publishing 1993: A multi-level analysis of feeding behaviour: the geometry of nutritional decisions [animal study, very weak evidence]

Animal Behaviour 1993: The geometry of compensatory feeding in the locust [animal study, very weak evidence] ↩

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2008: Lifespan and reproduction in Drosophila: New insights from nutritional geometry [animal study, very weak evidence] ↩

An extensive review found evidence for an increased risk of heart disease and all-cause mortality, albeit extremely small with a hazard ratio of 1.03.

JAMA Internal Medicine 2020: Associations of processed meat, unprocessed red meat, poultry, or fish intake with incident cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality [nutritional cohort study with HR<2; very weak evidence]

And a 2021 observational study from Italy reported a lower risk of all-cause mortality in people who ate MORE animal protein. While this doesn’t prove animal protein is protective, it certainly questions if it can be harmful when the highest consumers are living longer.

Journal of Gerontology 2021: Animal protein intake is inversely associated with mortality in older adults: the InCHIANTI study [nutritional epidemiology study with HR<2, very weak evidence]

↩Cell Metabolism 2014: Low protein intake is associated with a major reduction in IGF-1, cancer, and overall mortality in the 65 and younger but not older population [nutritional epidemiology study and animal study; very weak evidence] ↩

PLoS One 2017: Health outcomes of sarcopenia: A systematic review and meta-analysis [overview article; ungraded] ↩

American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2016: Mortality in vegetarians and comparable nonvegetarians in the United Kingdom [nutritional epidemiology study, very weak evidence]

American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2009: Mortality in British vegetarians: results from the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC-Oxford) [nutritional epidemiology study; very weak evidence] ↩

The following are low-quality nutritional epidemiology studies that suggest a minimal increased risk with red meat intake or a lower risk with eating plant protein. However, as we discuss in our guide on observational vs. experimental studies, this line of evidence is complicated by healthy user bias, poor data collection, confounding variables, and other methodological weaknesses.

JAMA Internal Medicine 2016: Association of animal and plant protein tntake with all-cause and cause-specific mortality [nutritional epidemiology study with HR<2; very weak evidence]

British Journal of Nutrition 2014: Association between total, processed, red and white meat consumption and all-cause, CVD and IHD mortality: a meta-analysis of cohort studies [observational study with HR < 2; very weak evidence]

Current Atherosclerosis Report 2013: Unprocessed red and processed meats and risk of coronary artery disease and type 2 diabetes – An updated review of the evidence [observational study with HR < 2; very weak evidence]

Journal of the American Heart Association 2017. Role of total, red, processed, and white meat consumption in stroke incidence and mortality: A systematic review and meta‐analysis of prospective cohort studies [observational study with HR < 2; very weak evidence]

BMJ: Risks of ischaemic heart disease and stroke in meat eaters, fish eaters, and vegetarians over 18 years of follow-up: results from the prospective EPIC-Oxford study [observational study; weak evidence]

Other studies show a link with processed meat but not minimally processed red meat.

Circulation 2010: Red and processed meat consumption and risk of incident coronary heart disease, stroke, and diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis [observational study with HR < 2; very weak evidence] ↩

MDPI 2020: The water footprint of global food production [overview article; ungraded] ↩

The following statement from the EPA shows that in the United States, all of agriculture (including plants and animals) contributes 10% of greenhouse gas emissions. Transportation, electricity, and industry contribute 77% of greenhouse gas emissions.

And, as this review explains, much of the greenhouse gas emissions ascribed to agriculture come from CO2 in much the same way transportation and industry contribute to CO2 emissions. Methane from ruminant animals acts significantly differently in the atmosphere than CO2, and its impact on the environment should be considered separately from agricultural CO2 emissions.

Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems 2021: Agriculture’s contribution to climate change and role in mitigation is distinct from predominantly fossil CO2-emitting sectors [overview article; ungraded] ↩