Time-restricted eating – a detailed intermittent fasting guide

How to improve:

- Overweight

- Obesity

- Type 2 diabetes

- Metabolic syndrome

- Insulin resistance

- Fatty liver

- High blood pressure

- High cholesterol

- High triglycerides

- …and many more…

By Doing ABSOLUTELY NOTHING!!

A guide by Ted Naiman, MD.

Time-restricted eating

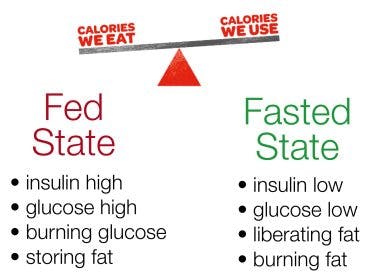

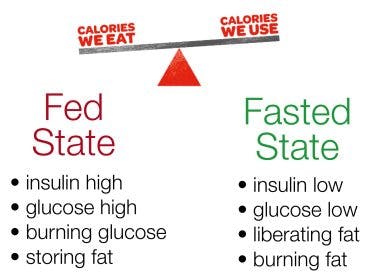

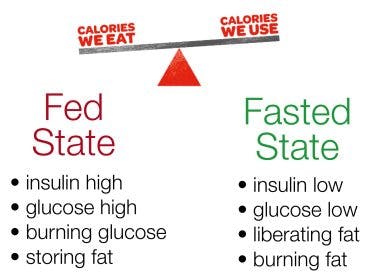

Fed vs. fasted

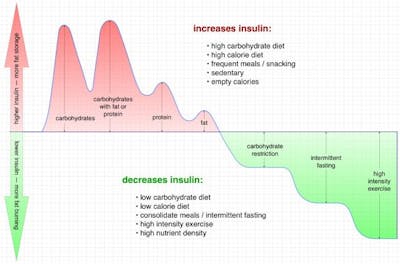

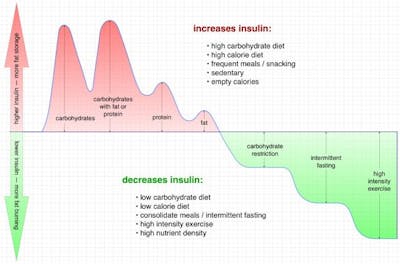

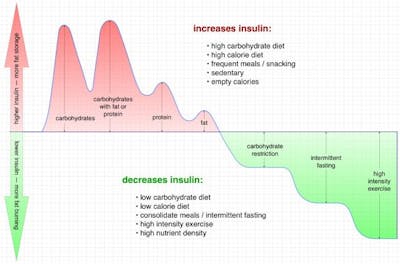

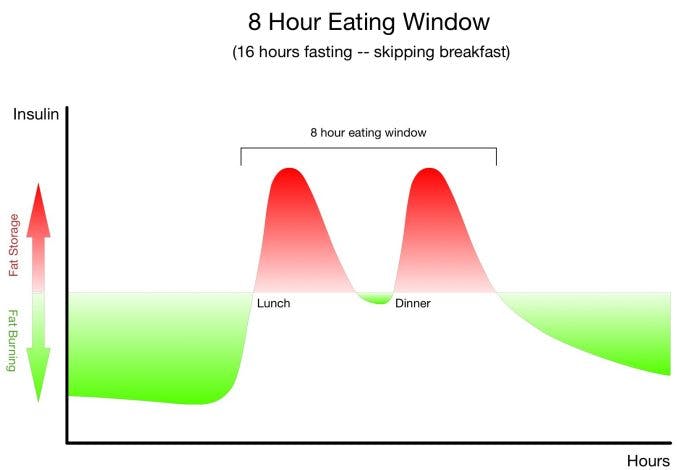

In the fed state, insulin tend to be elevated, and this signals your body to halt any fat burning, to store excess calories in your fat cells, and burn glucose (from your last meal) instead.1

In the fasted state, insulin is more likely to be lower (while glucagon and growth hormone, opposing hormones to insulin, are elevated).2 The body first burns stored glucose from glycogen, and then starts mobilizing stored body fat from your fat cells and burning it for energy (instead of glucose).

The practical importance of all this is that you can burn more stored body fat while in the fasted state, and you store more body fat while in the fed state.

Insulin resistance

Unfortunately, we seem to be spending less time in the fasted state and more time in the fed state.3 As a result, our cells spend less time mobilizing and burning stored body fat, and instead we continuously use the glucose-burning pathways. This leads to a chronic elevation of insulin and a near complete reliance on glucose.

Over time, this chronic exposure to too much insulin can lead to ‘insulin resistance’ where the body secretes even more insulin in response to the fed state.4 Chronic insulin resistance can lead to the ‘Metabolic Syndrome’: obesity, abdominal fat storage, high triglycerides, low HDL, and elevated glucose with eventual type 2 diabetes (1 in 12 humans on earth currently have full blown type 2 diabetes, while 35% of adults and 50% of older adults have Metabolic Syndrome, or pre-diabetes).5

Someone with insulin resistance is burning predominately glucose on the cellular level, and they rarely get the opportunity to burn any body fat. When these people run out of glucose from their last meal, instead of easily transitioning over to the fasted state to burn fat, it appears that they become hungry for more glucose (from carbohydrates) since their cells have decreased capacity for mobilizing and burning fat for energy.6 This pattern can start a cycle of eating every few hours, raising glucose and insulin, and then eating more when when blood sugar drops.

Let’s put it this way. Why would an obese person frequently feel hungry? They have enough fat stores to last a very long time. The world record for fasting went to a 456 pound man who fasted for 382 days, consuming only water and vitamins and losing 276 pounds with no ill effects (although we don’t recommend this!).7

But the average overweight person is used to being in the fed state, has very little practice in the fasted state, and is continually burning glucose rather than fat at the cellular level. They have insulin resistance, which is both caused by and also leads to chronically high insulin levels, which promotes fat storage and suppresses fat mobilization from the adipocytes (fat cells).8 They even have changes in the mitochondria, or tiny energy factories inside the cells.

The mitochondria can burn either glucose (sugar) or fat for fuel, and over time they will have a preference for one over the other; “sugar burners” have increased the pathways in the mitochondria that burn glucose and decreased, or down-regulated, the underused pathway for burning fat.9

A good analogy is that of a tanker truck on the freeway filled with oil. If the tanker truck runs out of gas it stops moving, despite the fact that it has 10,000 gallons of potential fuel on board. Why? Because it prefers to run on refined gas and is incapable of burning the stored oil for fuel.

Fat adaptation

This includes improving insulin sensitivity to lower insulin and promote fat mobilization into free fatty acids from the adipocytes (fat cells) as well as upregulating the fat-burning pathways at the cellular level (in the mitochondria).11 There are several ways to improve ‘fat adaptation’ or the ability to successfully burn stored body fat for energy, and these include the following:

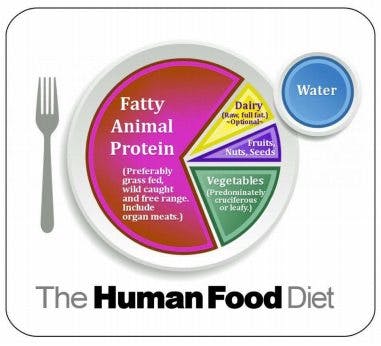

- Low carbohydrate diets. Eating a LCHF (Low Carb High Fat) diet improves the body’s ability to utilize fat for energy, as there is more fat and less glucose available at all times.12

- Exercise. High-intensity exercise depletes glucose and glycogen rapidly, forcing the body to switch over and utilize more fat for fuel. Exercise also improves insulin sensitivity.13

- Caloric restriction. Eating fewer calories also equals less glucose available for fuel, so the body is forced to rely on stored body fat for fuel. You will naturally eat the lowest calories when you maximize nutrient density by eating whole, natural, unprocessed foods found in nature.14

- Intermittent fasting, and spending more time in the fasted state, which gives the body more ‘practice’ at burning fat.15

Metabolic exercise

Intermittent fasting is a strategy for exercising and strengthening the body’s ability to exist in the fasted state, burning fat instead of continually burning sugar (glucose).

Just like anything else, this ability can be strengthened over time with practice. But this ability also atrophies or shrinks with lack of use, just like your muscles atrophy when you break your arm and have to wear a cast for weeks.16 You can consider spending time in the fasted state as a form of exercise—a METABOLIC WORKOUT.

In fact, there are many parallels between exercise and fasting. Exercise does all of the following beneficial things:17

- Decreases blood glucose.

- Decreases insulin level.

- Increases insulin sensitivity.

- Increases lipolysis and free fatty acid mobilization.

- Increases cellular fat oxidation.

- Increases glucagon (the opposite of insulin).

- Increases growth hormone (the opposite of insulin).

BUT did you know you can also accomplish all of the above by doing ABSOLUTELY NOTHING? The secret is *FASTING*.18

Extending the amount of time that you spend during your day in the FASTED state (as opposed to the FED state) can accomplish all of these, very similar to exercise. That is why I say extending time in the fasted state is a form of metabolic ‘exercise.’ It can ‘train’ your body to more efficiently mobilize free fatty acids from fat stores.

Just as overweight and out of shape people struggle to jog or lift weights or participate in other forms of physical exercise, they are also generally out of practice when it comes to mobilizing stored fat for fuel. Perhaps they just need more practice!

Less feeding, more fasting

One of the best ways to achieve effortless and long-lasting fat loss in my opinion is to train yourself to eat two meals a day (and eliminate snacking). The easiest and best way to accomplish this? Leverage your natural overnight fast by skipping breakfast (drinking coffee makes this easier and more enjoyable for some people).19

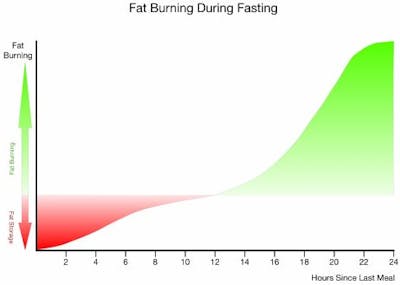

Typically, the fed state starts when you begin eating and for the next three to five hours your body digests and absorbs the food you just ate. Insulin rises significantly, completely shutting off fat-burning and also triggering excess calories to be stored as fat.20

After the first few hours mentioned above, your body goes into what is known as the post–absorptive state, during which the components of the last meal are still in the circulation. The post–absorptive state lasts until 8 to 12 hours after your last meal, which is when you enter the fasted state. It typically takes 12 hours after your last meal to fully enter the fasted state.21

Exercise helps

Exercise can also help with fat adaptation. Your glycogen (the storage form of glucose in your muscles and liver) is depleted during sleep and fasting, and will be depleted even further during training. This can further increase insulin sensitivity.23

Fasting myths

There are many myths about fasting:

“Breakfast is the most important meal of the day!”

We have all been told to eat breakfast. Unfortunately this is inaccurate advice.24

When you first wake up in the morning, your insulin level is quite low and most people are just starting to enter the fasted state, 12 hours after eating the last meal of the previous day. Eating at this time raises insulin and glucose and immediately shuts off fat-burning. This is especially true for a high carb breakfast. A potentially better choice would be to push the first meal of your day out at least a few hours, during which time you can continue in the fasted state and burn stored body fat.

Interestingly, many properly fat-adapted people aren’t very hungry in the morning and have no problem skipping breakfast.25

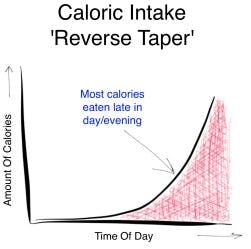

This is appropriate, as throughout our evolution humans were hunter-gatherers. Rather than eating a large breakfast first thing in the morning we would hunt and gather throughout the day, having a larger meal later in the day. I highly recommend mimicking this pattern by skipping breakfast.

“Eat small frequent meals.”

There has been plenty of troubling advice here. We have been told to eat frequently to “keep your metabolism going” and “don’t let your body enter starvation mode.” This is all likely the exact opposite of the truth: in order to burn fat, you want to spend as much time in the fasted state as possible and get very efficient at living on stored body fat rather than caloric intake from constantly eating.26

“Fasting leads to burning muscle instead of fat.”

Many people are concerned that if they start fasting they will either stop making muscle or maybe even burn muscle. If you are under weight and fast for a prolonged period of time, this may be true. Otherwise, this is simply not true.27

In fact, growth hormone is increased during fasted states (both during sleep and after a period of fasting).

“Your metabolism slows down when you are fasting.”

For shorter fasts, this is completely false. A number of studies have proven that in fasting up to 72 hours, metabolism does not slow down at all and in fact might speed up slightly thanks to the release of catecholamines (epinephrine or adrenaline, norepinephrine, and dopamine) and activation of the sympathetic nervous system (sympathetic nervous system is often considered the “fight or flight” system, while the opposite is the parasympathetic nervous system or the “rest and digest” system).29

It makes sense that this fight or flight sympathetic nervous system would be activated during the daytime, when hunter-gatherer humans are most active and in the fasted state (looking for food), followed by parasympathetic “rest and digest” mode in the evening after eating a large meal.

“If I don’t eat I will get low blood sugar [hypoglycemia].”

Studies have shown that healthy persons who have no underlying medical conditions, who are not taking any diabetes medications, can fast for long periods of time without suffering from hypoglycemia.30 In fact, many people find sensations of hypoglycemia or low blood sugar (in non-diabetics) result from eating a very high glycemic index food a few hours prior (blood sugar spikes, then insulin spikes, then blood sugar drops rapidly).31

However if you are a diabetic, especially if you are on any diabetes medications, you definitely need to check with your doctor before starting a fasting protocol. Some diabetes medications can lead to severe hypoglycemia when fasting (mostly insulin and sulfonylurea drugs like glipizide, glimepiride, and glyburide). [Be sure to check with your doctor prior to starting a fasting protocol if you have any medical problems, diabetes or otherwise. You and your doctor can use our guide for low carb diets and diabetes medications as the same concepts apply to fasting.]

How to fast intermittently

There are a number of ways to actually perform intermittent fasting, but the easiest and most popular varieties involve taking advantage of your natural overnight fast by skipping breakfast and pushing the first meal of the day forward a number of hours.32 Once you have passed the 12 hour mark from dinner the night before, you are truly in a fasted state and you begin to rely on stored body fat for fuel.33

It is likely that the longer you stay in the fasted state, the deeper your fat adaptation will get. In fact, if you can maintain this intermittent fast for 20 to 24 hours you may achieve an even higher rate of lipolysis (breakdown of stored body fat into free fatty acids, available for burning in the cells) and fat oxidation (burning of fat in the mitochondria).34

When you first start out with intermittent fasting, you may feel hungry and low energy. In this case I recommend starting out with “baby steps”, by just pushing breakfast out an hour or two at first, then slowly increasing the fasting interval. As time goes by and you become more “fat adapted”, it is easier to fast. This is identical to exercise in those who are sedentary: it is painful and extremely difficult at first, and then once you are adapted it gets easy and even enjoyable.35

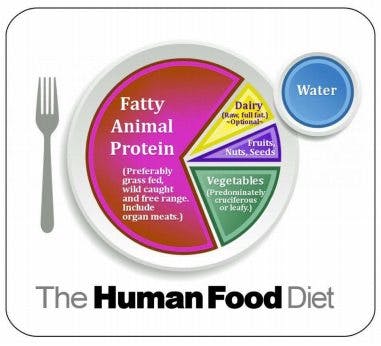

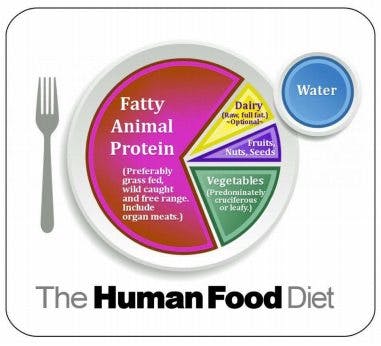

LCHF diet for fat adaptation

Many individuals and clinicians find it easier to fast if you are already on a low-carb (low carb high fat) diet, as these diets naturally lead to fat adaptation and are naturally lower insulin secretion and glucose utilization.36 In fact, I HIGHLY recommend the combination of a very low carb diet with intermittent fasting.

The closer you get to a ketogenic diet (extremely low in carbohydrates, moderate in protein, and high in fat) the easier it is to go for hours and hours without eating.37

For those who do incorporate carbohydrates in the diet, I would recommend that these mostly consist of FIBER, which is indigestible and does not contribute to the elevation of glucose and insulin and can also add to satiety.38 If you do decide to eat digestible carbohydrates, I recommend not eating these first thing in the morning, as this can contribute to fat storage and sabotage fat burning, as well as setting you up for a blood sugar and hunger roller coaster for the rest of the day.39

Popular forms of intermittent fasting

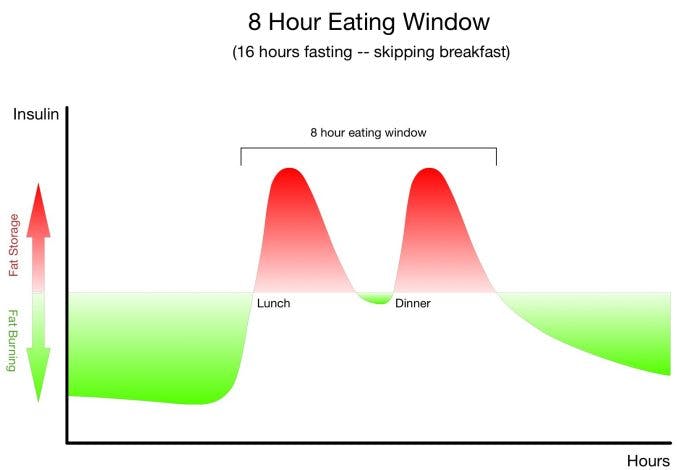

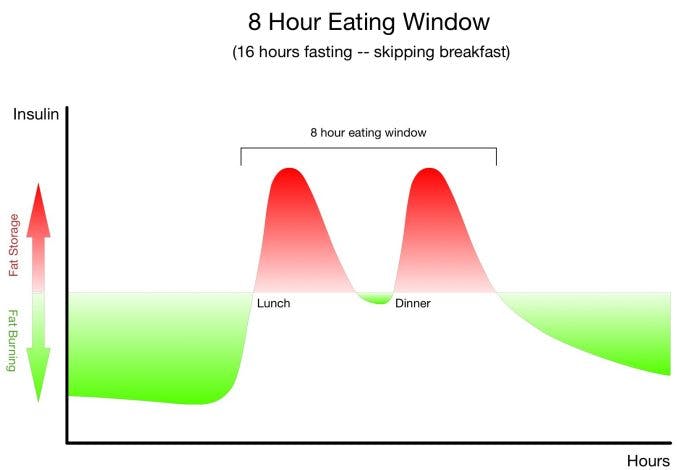

Leangains – also called 16:8

Leangains, as popularized by bodybuilder Martin Berkhan, is by far the most popular method of fasting intermittently. This form of fasting consists of skipping breakfast every morning and pushing the first meal of the day to lunch, eating within an eight hour window. The idea is to fast for 16 hours (overnight plus the first ~6 hours of your day), then eat all your calories in an 8 hour window.

For example, let’s say you get up at 6:00 a.m. You would skip breakfast and eat nothing for six hours, then lunch at noon and dinner at 8:00 p.m. Snacking inside your eating window is allowed (although I will say that generally speaking you want to try to consolidate calories into larger meals rather than snacking). This 16:8 split (16 hours fasting and 8 hours eating) is recommended every single day.

If you had one day off from this protocol and followed this the other six days of the week, that would amount to an additional 4 hours of fasting per day compared to the standard 12:12 split that we are assuming to be baseline (12 hours fasting and 12 hours eating). Four hours per day times six days per week equals about 24 hours of total additional fasting per week. [4 hours fasting per day times 6 days per week = 24 hours]

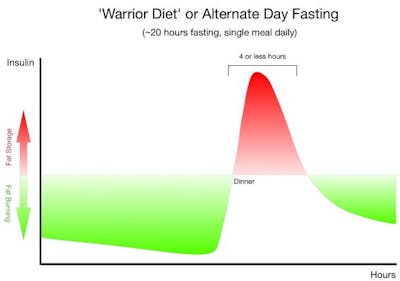

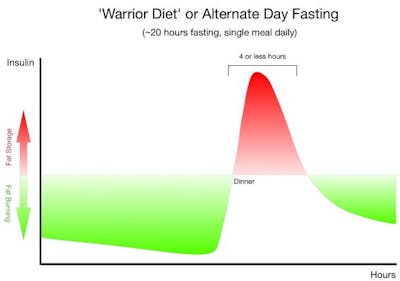

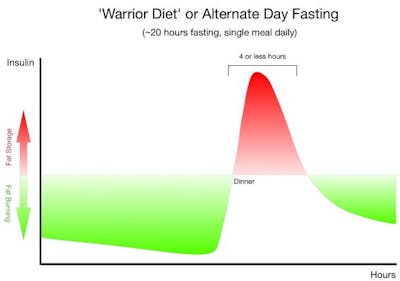

Warrior diet

The Warrior Diet, as popularized by Ori Hofmekler, consists of fasting during the majority of the day, then eating all of your calories in the evening. The goal is to skip breakfast and lunch, then eat a large dinner in a four hour window at the end of the day. This is a 20:4 hour split (20 hours of fasting and then a 4 hour eating window at the end of the day).

This method of fasting does allow you to eat very large very satisfying meals at the end of the day, and might be perfect for someone who was going out to dinner to eat in a social setting, where a ton of calories and food might be involved (like one of those all-you-can-eat Brazilian steak houses!).

Fasting this long during the day can be more difficult for some, but it may also lead to a deeper level of fat adaptation and lower insulin. If one followed this protocol roughly every other day (let’s say three days a week), that would equate to eight extra hours of fasting compared to the 12:12 baseline standard diet, times three days per week would also equal about 24 hours of total additional fasting per week. [8 hours fasting per day times 3 days per week = 24 hours]

Eat stop eat

Eat Stop Eat, as popularized by bodybuilder Brad Pilon, involves fasting for an entire 24 hours, two days per week. Let’s say you eat your last meal of the day at 8:00 p.m. the day before. You fast overnight and then all the following day, skipping breakfast and lunch, and then pushing dinner out to 8:00 p.m. (for a full 24 hours with no calories).

I only recommend this two days per week (nonconsecutive). Many people think that the following day they will binge on so much food that the benefits of the fasting on the previous day will be negated, but this is usually not true, especially if you are consciously aware of the risk.40

Studies have repeatedly shown that persons may overeat by a couple hundred calories the next day, but still not come anywhere close to eating as much as they would have by eating normally both days (in other words, you are still left with a net caloric deficit even after eating more food the day after your fast).41

Each day that you fast in this fashion adds 12 hours of fasting compared to the standard 12:12 split we are calling baseline, and two days per week of this again equals about 24 hours of total additional fasting per week. [12 hours fasting per day times 2 days per week = 24 hours]

It’s all good

With all of these fasting methods, the goal is to skip a meal or two, avoid snacking, and consolidate calories. All of these methods are effective, and you can mix and match these as much as you would like. I would highly recommend keeping it flexible. Fast for as long as is convenient on any given day, and break your fast whenever you need to or want to. Anything beyond a 12 hour window is going to be at least somewhat beneficial towards anyone’s goals.42

If you planned on fasting 16 hours but only make it 14, that’s ok and you are still much better off than if you had eaten all day long. I think a good goal would be 24 hours per week of additional fasting (additional to the standard 12:12 baseline).43 This could be 2 days of 24 hour fasting (Eat Stop Eat), 3 days of 8 hour fasting (Warrior Diet), or 6 days of 4 hour fasting (Leangains).

Coffee = awesome

During the fasts feel free to drink ANY noncaloric beverage you want, including but not limited to: water, coffee, tea (hot or iced), or any other beverage with no calories. However I would NOT recommend any calories AT ALL, as it takes frightfully few calories to increase insulin and sabotage your fast.44 Fat is the macronutrient that raises insulin the very least, which is why so many people are adding fat (butter, coconut oil, etc) to coffee in the morning.

However, I do not routinely recommend this or any other source of calories while fasting, as this may limit some of the benefits of fasting. If you will absolutely “die” without at least a tiny splash of cream or fat in your coffee, well then do it.45 You will likely be better off with it than if this prohibition against fat in your coffee keeps you from trying to fast intermittently at all (95% fasting much better than 0% fasting)!46

However I would try to keep the cream in your coffee to an absolute MINIMUM quantity, and you should also use this opportunity to learn to drink coffee black (this is something anyone can learn over time, believe it or not).

Enjoy your newfound freedom from food

Once you are properly fat adapted, intermittent fasting can be easy, fun, enjoyable, and liberating—while making you leaner and healthier in the process! Let’s say you are following the Leangains protocol. Breakfast every day during the work week is now just black coffee, tea or water, how easy is that? No more worrying about what you are going to grab for breakfast as you rush around in the morning and struggle to get to work on time or get the kids ready for school.

This saves you time, work and effort and is literally a form of metabolic exercise! In the meantime, you are improving your insulin sensitivity and strengthening your fat adaptation. This is a win in many ways. It frees you to eat large and satisfying meals later without feeling the deprivation, without watching calories, and without restricting yourself.

And on days where you skip breakfast and lunch, you will be amazed at how much extra time you have not worrying about what to eat, where to get it, and when to find time to eat it. Your productivity will be higher and you will have more free time. (please read our guide on OMAD for more potential benefits and concerns about eating one meal per day).

Some pointers47

- Check with your doctor before initiating intermittent fasting, ESPECIALLY if you are diabetic and on diabetes medications!

- You can generally take any vitamins or supplements you want while fasting as long as they don’t have calories, but you don’t need any supplements as you will be eating plenty of nutrient-dense foods every day.

- You don’t have to worry about losing muscle from lack of protein during your fast, as long as you eat adequate protein at the meals before and after fasting.

- You will not lose muscle while fasting as long as you are exercising regularly, and I specifically recommend resistance training such as lifting weights.

- Following a LCHF (low carb high fat) diet pairs nicely with intermittent fasting, as both improve fat adaptation.

- It is perfectly fine to exercise while fasting, either cardio or lifting weights (lifting weights is better for body composition and I highly recommend it for everyone, as this will further your goals considerably) See our guide on exercise to decide what type of exercise best suits your goals.

- Drink plenty of water and non-caloric beverages while fasting; coffee and tea in the morning make fasting considerably more enjoyable.

- Don’t use intermittent fasting as an excuse to eat tons of junk food when you are eating—continue to eat responsibly, sticking with whole natural foods with high nutrient density and avoiding highly processed foods!

More

Intermittent fasting for beginners

Greenspan’s Basic & Clinical Endocrinology, 10e 2018: Chapter 17: Pancreatic Hormones and Diabetes Mellitus [textbook; ungraded]

Clinical Biochemical Reviews 2005: Insulin and insulin resistance. [overview article; ungraded] ↩

Biochemistry: 5th edition: Section 30.3 Food intake and starvation induce metabolic changes [textbook article; ungraded]

Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 1992: Augmented growth hormone (GH) secretory burst frequency and amplitude mediate enhanced GH secretion during a two-day fast in normal men. [nonrandomized study, weak evidence] ↩

Journal of Nutrition 2010: Snacking increased among U.S. adults between 1977 and 2006. [observational study, weak evidence] ↩

Greenspan’s Basic & Clinical Endocrinology, 10e 2018: Chapter 17: Pancreatic Hormones and Diabetes Mellitus [textbook; ungraded]

Clinical Biochemical Reviews 2005: Insulin and insulin resistance. [overview article; ungraded] ↩

Diabetologia 1991: Hyperinsulinaemia: the key feature of a cardiovascular and metabolic syndrome. [observational study, weak evidence]

Diabetes 2018: Global prevalence of type 2 diabetes over the next ten years (2018-2028) [review of observational studies; weak evidence]

Medicine 2014: Epidemiology of diabetes [review of observational studies; weak evidence]

CDC.gov: New CDC report: More than 100 million Americans have diabetes or prediabetes [CDC Report article; ungraded]

↩This is difficult to “prove” in a scientific study, but a combination of clinical experience and mechanistic studies support the theory of why increased hunger frequently goes along with higher carb diets. ↩

Postgraduate Medical Journal 1973: Features of a successful therapeutic fast of 382 days’ duration. [single case study report; very weak evidence] ↩

Greenspan’s Basic & Clinical Endocrinology, 10e 2018: Chapter 17: Pancreatic Hormones and Diabetes Mellitus [textbook; ungraded]

Journal of Endocrinology 2017: A causal role for hyperinsulinemia in obesity [overview article; ungraded]

↩Endocrinology Review 2018: Metabolic Flexibility as an Adaptation to Energy Resources and Requirements in Health and Disease. [overview article; ungraded] ↩

Metabolism 2016: Metabolic characteristics of keto-adapted ultra-endurance runners. [case-control study, weak evidence] ↩

Annual Review of Nutrition 2006: Fuel metabolism in starvation. [overview article; ungraded] ↩

American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2007: Low-carbohydrate nutrition and metabolism [overview article; ungraded] ↩

NEJM 1996: Increased glucose transport-phosphorylation and muscle glycogen synthesis after exercise training in insulin-resistant subjects. [nonrandomized study, weak evidence]

Journal of Applied Physioology 1985: Invited review: Effects of acute exercise and exercise training on insulin resistance. [overview article; ungraded]

↩American Journal of Physiology, Endocrinology and Metabolism 2010 Calorie restriction increases fatty acid synthesis and whole body fat oxidation rates. [animal study, weak evidence] ↩

Obesity 2019: Early time-restricted feeding reduces appetite and increases fat oxidation but does not affect energy expenditure in humans. [nonrandomiazed study, weak evidence] ↩

This is based on consistent clinical experience of low-carb practitioners. [weak evidence] ↩

Diabetes Care 2006: Effects of different modes of exercise training on glucose control and risk factors for complications in type 2 diabetic patients [systematic review of randomized trials; strong evidence]

Obesity Reviews 2015: The effects of high-intensity interval training on glucose regulation and insulin resistance: a meta-analysis. [systematic review of randomized trials; strong evidence]

Medicine Science Sports and Exercise 2009: Minimal resistance training improves daily energy expenditure and fat oxidation. [randomized trial; moderate evidence]

Canadian Journal of Physiology and Pharmacology 1997: Glucose metabolism during exercise in man: the role of insulin and glucagon in the regulation of hepatic glucose production and gluconeogenesis.

[overview article; ungraded]Journal of Applied Physioology 1985: Invited review: Effects of acute exercise and exercise training on insulin resistance. [overview article; ungraded]

Sports Medicine 2003: The exercise-induced growth hormone response in athletes. [overview article; ungraded]

↩NEJM 2019: Effects of intermittent fasting on health, aging, and disease. [overview article; ungraded] ↩

This is based on clinical experience of low-carb practitioners and was unanimously agreed upon by our low-carb expert panel. You can learn more about our panel here [weak evidence]. ↩

Greenspan’s Basic & Clinical Endocrinology, 10e

2018: Chapter 17: Pancreatic Hormones and Diabetes Mellitus

[textbook; ungraded] ↩Biochemistry: 5th edition: Section 30.3 Food intake and starvation induce metabolic changes [textbook article; ungraded] ↩

Cell Metabolism 2020: Ten-hour time-restricted eating reduces weight, blood pressure, and atherogenic lipids in patients with metabolic syndrome. [observational study, weak evidence]

Translational research 2014: Intermittent fasting vs daily calorie restriction for type 2 diabetes prevention: a review of human findings [observational study, weak evidence] ↩

Diabetes Care 2006: Effects of different modes of exercise training on glucose control and risk factors for complications in type 2 diabetic patients [systematic review of randomized trials; strong evidence]

Obesity Reviews 2015: The effects of high-intensity interval training on glucose regulation and insulin resistance: a meta-analysis. [systematic review of randomized trials; strong evidence]

Medicine Science Sports and Exercise 2009: Minimal resistance training improves daily energy expenditure and fat oxidation. [randomized trial; moderate evidence]

Canadian Journal of Physiology and Pharmacology 1997: Glucose metabolism during exercise in man: the role of insulin and glucagon in the regulation of hepatic glucose production and gluconeogenesis.

[overview article; ungraded] ↩The old idea that breakfast is important for health or weight control is mainly based on observational studies, a notoriously weak form of evidence.

When tested this idea does not appear to hold up, at least not for weight loss. A recent meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials found that people assigned to skip breakfast ate less overall and lost more weight than those assigned to eat breakfast daily:

British Medical Journal 2019: Effect of breakfast on weight and energy intake: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials [strong evidence]

Even the observational data is inconsistent, for example with findings like in the study below: “compared to breakfast eating, skipping breakfast was significantly associated with better health-related quality of life and lower perceived stress.”

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2018: Eat or skip breakfast? The important role of breakfast quality for health-related quality of life, stress and depression in Spanish adolescents [weak evidence] ↩

This is based on clinical experience of low-carb practitioners and was unanimously agreed upon by our low-carb expert panel. You can learn more about our panel here [weak evidence]. ↩

The following randomized crossover trial showed no difference in energy expenditure or fat oxidation between 3 and 6 meals per day, but did see a probable increase in hunger with more frequent eating. This shows a lack of increased metabolism with more frequent eating.

Obesity 2013: Effects of increased meal frequency on fat oxidation and perceived hunger. [randomized trial; moderate evidence]

And the following trial showed an increased in resting metabolism with short term fasting

American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2000: Resting energy expenditure in short-term starvation is increased as a result of an increase in serum norepinephrine [weak evidence]

↩Research suggests that when obese people fast, hormonal changes occur that lead to a decrease in total body protein breakdown, which includes muscle:

American Journal of Public Health and the Nation’s Health 1968: Influence of fasting and refeeding on body composition [weak evidence]

Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 1983: Whole body protein breakdown rates and hormonal adaptation in fasted obese subjects [weak evidence] ↩

This RCT showed a significant rise in growth hormone in a 24 hour fast.

Nutrition, Metabolism and Cardiovascular Diseases 2013: Randomized cross-over trial of short-term water-only fasting: metabolic and cardiovascular consequences [moderate evidence] ↩

In a 2016 randomized, controlled study, obese adults were assigned to either fast every other day or eat a calorie-restricted diet every day. Those in the intermittent fasting group showed less slowing in metabolic rate during the 8-week study and greater improvement in body composition after 32 weeks of follow up compared to people in the calorie-restricted group:

Obesity (Silver Spring) 2016: A randomized pilot study comparing zero-calorie alternate-day fasting to daily caloric restriction in adults with obesity [moderate evidence]

These other studies likewise show an increase, or at least no decrease, in metabolic rate of metabolism.

American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2007: A controlled trial of reduced meal frequency without caloric restriction in healthy, normal-weight, middle-aged adults [moderate evidence]

American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2000: Resting energy expenditure in short-term starvation is increased as a result of an increase in serum norepinephrine [weak evidence]

The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2005: Alternate-day fasting in nonobese subjects: effects on body weight, body composition, and energy metabolism [weak evidence]

↩European Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2007: Effect of fasting on young adults who have symptoms of hypoglycemia in the absence of frequent meals [observational study, weak evidence] ↩

This is based on consistent clinical experience of low-carb practitioners. [weak evidence] ↩

This is based on consistent clinical experience of low-carb practitioners. [weak evidence] ↩

Greenspan’s Basic & Clinical Endocrinology, 10e 2018: Chapter 17: Pancreatic Hormones and Diabetes Mellitus

[textbook; ungraded] ↩Although there aren’t any head-to-head comparative trials of different levels of time restricted eating, in theory longer fasts would help with greater fat oxidation [very weak evidence] ↩

This is based on consistent clinical experience of low-carb and lifestyle practitioners. [weak evidence] ↩

This is based on clinical experience of low-carb practitioners and was unanimously agreed upon by our low-carb expert panel. You can learn more about our panel here [weak evidence].

In addition, studies show very low carb diets reduce hunger, which in theory could make fasting easier.

Obesity Reviews 2015: Do ketogenic diets really suppress appetite? A systematic review and meta-analysis. [systematic review of randomized trials; strong evidence] ↩This is based on consistent clinical experience of low-carb practitioners. [weak evidence] ↩

Journal of Nutrition 2000: Dietary fiber and energy regulation. [overview article; ungraded] ↩

This is based on consistent clinical experience of low-carb practitioners. [weak evidence] ↩

International Journal of Obesity Related Metabolic Disorders 2002: Effect of an acute fast on energy compensation and feeding behaviour in lean men and women. [randomized trial; moderate evidence] ↩

Cell Metabolism 2020: Ten-hour time-restricted eating reduces weight, blood pressure, and atherogenic lipids in patients with metabolic syndrome. [observational study, weak evidence] ↩

Experimental studies have yet to define how many calories “break” a fast, but clinical experience suggest it can be very few for many individuals. Studies also have not show if breaking a fast is an all-or-none event or if reduced caloric intake in the morning can still mimic many of the benefits of time restricted eating. That is why many practitioners err on the side of caution and suggest no caloric intake at all [anecdotal reports; very weak evidence] ↩

Some people find that a little fat in the morning helps them maintain a longer fast, where as in the absence of that fat they cannot maintain a fast. This clearly varies from person to person. ↩

This is based on consistent clinical experience of low-carb practitioners. [weak evidence] ↩

This is based on consistent clinical experience of low-carb practitioners. [weak evidence] ↩