Journalist Nina Teicholz:

In the world of nutrition, a bulldozer for truth

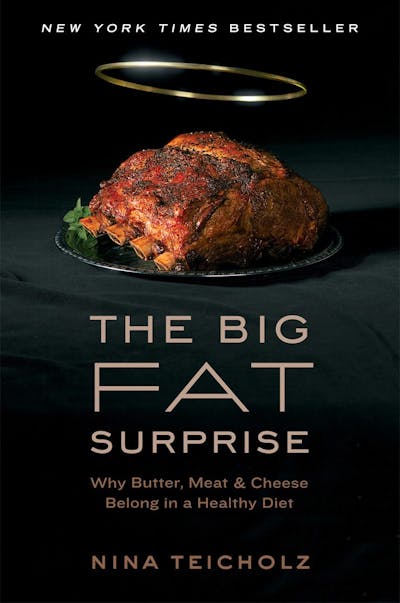

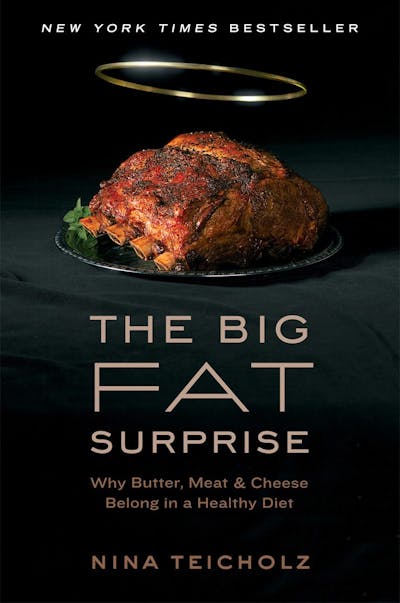

Nina Teicholz’s 2014 book The Big Fat Surprise: Why Butter, Meat & Cheese Belong in a Healthy Diet is a bestseller that continues to get kudos for its meticulous research, engaging writing and iconoclastic takedown of the 60-year war against dietary fat.

The book was named a “best book” of the year by The Economist, The Wall Street Journal, Fortune Magazine, Mother Jones, Library Journal, and Kirkus Reviews. The influential Economist dubbed it a compelling “page turner,” and the Lancet, read by tens of thousands of doctors worldwide, called it a “gripping narrative”, a must-read exposé of the weak science and downright bias that led to the erroneous demonization of saturated fat.

How did Nina Teicholz come to write her book and emerge as a leading voice advocating for the use of rigorous science in nutrition? Here is her story.

Discovering the truth

Nina Teicholz had the first inkling that maybe dietary fat was not the bogeyman it was made out to be — at least for weight gain — around 2003. As a freelance journalist in New York City, she got a side gig reviewing restaurants for a city publication.

As she describes in a 2014 Family Circle article, up until that point, as an adult, she had eaten a near-vegetarian diet, eschewing meat, butter, eggs, cheese and cream in favour of fruits, vegetables and healthy grains. She thought eating that way was better for her health and her figure, even though she always seemed to hang onto a stubborn 10lbs that didn’t budge, no matter how much she exercised.

And she exercised a lot — almost daily. “I used to really devote time to exercise — about an hour and a half out of my day to go biking or running. I loved it, but I also felt it was an obligation so that I wouldn’t gain weight.”Her restaurant reviewing gig had chefs placing signature high-fat meals before her with savoury cream sauces, choice cuts of succulent meat, rich pâté and decadent cheeses. And much to her surprise, over two months of eating this way, instead of ballooning up in pounds as she had feared, she lost that extra 10 lbs with no need for more exercise. Moreover, the meals were satisfying and delicious. What the heck was going on?

She was freelancing as a journalist for multiple publications at the time, including The New Yorker, The New York Times, Men’s Health and particularly Gourmet. “Gourmet was a big food magazine in the U.S., and they were just getting interested in more rigorous investigative stories on food systems.”

Around the time of her own discovery that eating fat had not made her fat, the magazine assigned her an investigative story on trans fats, the industrial fat created by adding extra hydrogen atoms onto vegetable oils to make them solid and more stable at room temperature. That assignment set her down a 10-year rabbit hole investigating the science and politics of all fats and oils. “And that is really the beginning of this whole chapter of my life.”

A unique background

If Nina’s life were a book, made up of distinct chapters, the plot line before encountering the world of nutrition was certainly experimental and nonlinear.

“I don’t really have a linear story!” laughs Nina, now 52, explaining a highly diverse resume that includes stints bumming around Latin America, post-graduate studies at Oxford in Latin American Studies, and a 2-year posting to Brazil as a journalist working for National Public Radio (NPR.)

Some of that may come from her family. “We were an equal mix of art and science.” She grew up in Berkeley, California as the middle of three children in an academically-inclined family. Her father, a mathematics, computer and engineering “brain” founded the Center for Integrated Facility Engineering at Stanford University, which brings computer-based tools to building and construction. Her mother earned a degree in art history and became a curator, specializing in Asian art, at The University Art Museum at Berkeley.

Nina was a good student who loved science. In her first year of university at Yale, she studied biology, but it wasn’t a good experience. “There was a level of competition and lack of support that was quite alienating.” She will never forget the academic advisor who showed “zero interest in me as a student” and the organic chemistry prof who said “your job is to do as well as you can in class and my job is to make you fail.”

She transferred to Stanford where she completed a major in American studies, with a minor in human biology, a unique combination that perfectly suited the eventual investigation and writing of her book. “In my research into nutrition science, at least half of it is politics. Understanding how U.S. institutions work, or don’t work, or how they become co-opted, is as central to this story as the science itself.”

After travelling in Latin America and completing post-grad studies at Oxford, she moved to Washington, D.C., where she decided she wanted to be a journalist. “Journalists were always the most interesting people I met. They had the most flexible and interesting minds that ranged the farthest, and they had the most interesting discussions.”

She started with an internship at National Public Radio (NPR), and worked her way up over the next five years leading to the two years living in Brazil and reporting on stories all over South America. Eventually she wound up in New York, “the center of journalism” and began freelancing for publications.

“Entering in through the trans-fat door”

Her 2003 piece on trans fats for Gourmet was a blockbuster, gaining wide circulation and garnering her a six-figure advance for a book on trans fats.

Looking back, Nina is very grateful that she spent the first three years of her research “entering in through the trans fat door, getting to know all about the vegetable oil industry.” Industry executives were very open to her. “I had wide open access because at that point, I was just learning. I asked for people’s time and they gave it. No battle lines had yet been drawn.”

This research gave her an unique understanding about the power of the vegetable oil industry and how it had manipulated nutrition science—in particular, the “diet-heart hypothesis,” which holds that saturated fat causes heart disease. She even learned that Proctor & Gamble, the makers of Crisco Oil (a hardened oil with trans fats), helped raise millions of dollars which enabled the American Heart Association to go from a small volunteer organization to a national powerhouse.

Realizing the magnitude of the situation

“I got to understand the magnitude of the vegetable oil industry and how important the demonization of saturated fat was to them. How much they had influenced the science, funded the science. How powerful they were,” said Nina.

She soon realized she was on to a much, much bigger story — that everything we have been told about fat for more than 50 years is wrong. Some sources were too afraid to talk to her. “I would get off the phone and be shaking, like, I am investigating the underworld? As a journalist, when you realized that someone is afraid to talk to you, you know there is a big story there.”As an accomplished journalist working on such an important topic, did she ever have a moment’s doubt that the book would be a tour de force that would shake the very foundations of nutrition science?

“Oh my goodness, it was incredibly stressful. As my conclusions became more solid, almost every night I would lie down on the floor of my husband’s study and say ‘I just can’t do this! How can I be right and everyone else be wrong? It can’t be possible.’ And then I would spend hours and hours trying to disprove myself. Is my data solid? Is there any way this could be wrong?”

Bumps in the road

A definite low in the writing process came in the first few years when her first publisher dropped the book because she hadn’t turned it in on time. Nina had to not only pay back her advance but then had to soldier on, alone without support, for almost a year before Simon and Schuster purchased the book for a much smaller advance. To support her and her two children, she relied on her husband’s income and used all the money from an inheritance from her grandmother, to enable her to continue writing a book that was taking much longer than she, or anyone, expected.

“It was a difficult time. And the longer it took, the more everybody was embarrassed to ask me, ‘Are you still writing your book?’ and I would say ‘Yes, I am still writing the book.’ There is such a fear you will never finish.”

Bulldozers of truth

But with her dogged focus that bordered on obsession, a supportive family, an unflagging editor and a tenacious agent, after more than nine years, the book was finally done. “My editor, agent and I called ourselves the “bulldozers of truth” — we felt we just had to get the truth out into the world.”The result, as almost all the reviews note, is a gripping read about co-opted science, often funded by vegetable oil industry, that led to the shunning of saturated fat for almost 50 years — and very likely contributed to the obesity and diabetes epidemics.

“What Nina Teicholz has done and continues to do is very brave and very important. The resistance she has faced and the personal attacks have truly been remarkable,” says Dr. Andreas Eenfeldt, founder of Diet Doctor. “For example a high-profile MD affiliated with Yale called her “shockingly unprofessional”, “an animal” and more in a Guardian article. But he failed to provide any examples of this unprofessional behavior, despite several requests from the journalist. I think many experts have been living comfortably in dogma for decades. When they get intellectually challenged by a woman, a journalist, and they fail to find any good arguments, some of them just lose it, and lash out at her. The truth is often inconvenient and uncomfortable.”

The personal attacks have been difficult, says Nina. “On the one hand, the attacks are painful and hurtful, but at the same time, you know that if they are attacking you personally it is because they cannot attack you substantively. One has to stay above the fray and not stoop down to their level of name-calling. Their level is so low, it’s embarrassing – and it certainly doesn’t help the scientific discussion.”

Since 2004, she herself has embraced the low carb, high fat diet. Now she relishes juicy steaks, plenty of cheese, and lots of butter — and feels at her healthiest, and effortlessly at the thinnest, of her entire life.

“Everyone who switches to this diet just marvels at how delicious all this food is that has previously been forbidden. It is an incredible liberation to not be counting calories and to live in a way where food is no longer your enemy. I really would have appreciated knowing all of this when I was a young woman, when I always wanted to be thin and 10 pounds lighter.”

Current work and future plans

Is another book underway? Not at the moment. Currently, almost 100% of her time is occupied working with leading the Nutrition Coalition, the non-profit organization she founded to ensure the U.S. nutrition policy, especially its influential dietary guidelines, is evidence based. Working closely with Dr. Sarah Hallberg, who directs the Nutrition Coalition’s Scientific Council, her goal is to get the U.S. Dietary Guidelines reformed by their next iteration, in 2020.

“The Dietary Guideline imposes profound rigidities on both the medical and food systems in the U.S. We have to remove that rigidity to give doctors the freedom to prescribe different diets, including — for instance, a low carb, high fat diet, for patients with obesity, Type 2 diabetes, or other nutrition-related diseases. There is no single, more powerful lever on the way America eats than the U.S. dietary guidelines. And that is why they need to change.”

Is she optimistic? Certainly more so now, with the community of world-wide individuals who are being brought together online.

“It is such a wonderful community of people. Everyone shares a common goal. All are so grateful for their newly-found health and wellbeing. There is a sense of purpose and a collectivity that is really a beautiful thing. I think we are lucky to be where we are at this moment in time.”