The science of low carb and keto

For each topic (e.g. weight loss), we briefly describe notable features of the most relevant clinical trials, meta-analyses/systematic reviews, and sometimes observational studies (when the number of intervention trials is small or the observational findings are very strong).

At the end of each section, we link to our most relevant guides, where you can further explore each topic in greater depth.

Please note that we have tried to make our list of studies comprehensive, with some qualifications. First, with respect to meta-analyses and systematic reviews, we generally focus on the most recent five years. This type of research will include most clinical trials to date, thereby making newer reviews more comprehensive than older ones. In cases where there aren’t many reviews within the last five years, we look back over ten years.

Second, we may exclude papers that we feel are not relevant to real-world or long-term clinical management. For example, in many of our sections, we exclude short trials of just several weeks; it’s simply too difficult to extrapolate their findings to many chronic medical conditions.

Third, the volume of medical literature is constantly expanding at a rate that makes it difficult to catch every relevant study. If you think we have missed an important paper, please email the citation to bret@dietdoctor.com.

.Weight loss

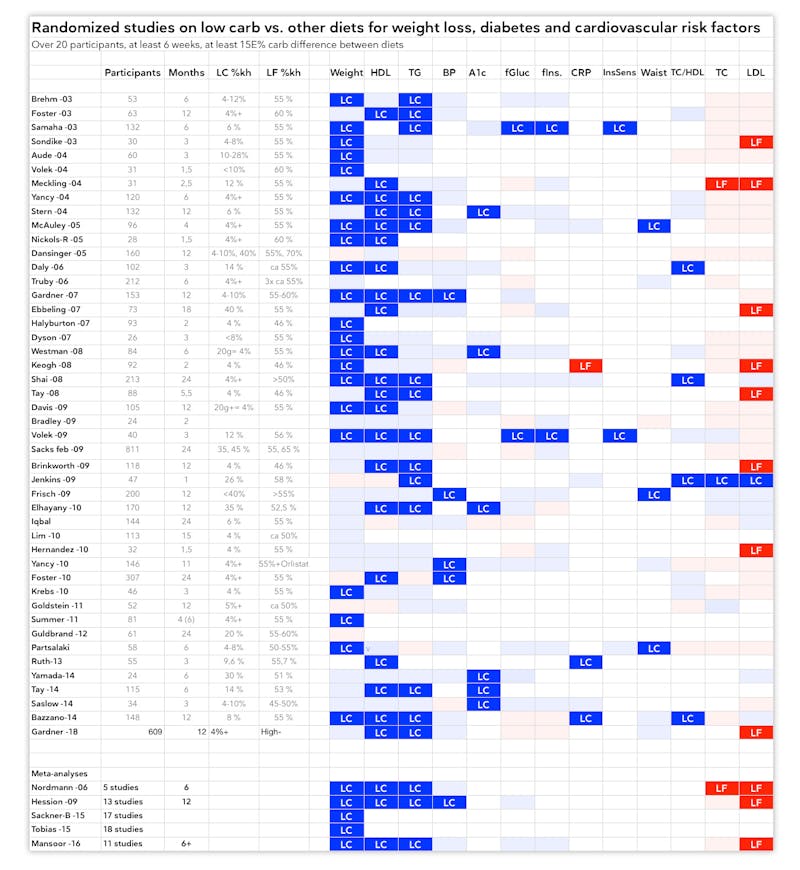

There is little evidence in the scientific literature that decisively indicates any particular diet is superior for helping people lose weight and maintain that loss for more than two years. In fact, most people who use a diet to lose weight regain most or all of it.1 With those caveats, randomized controlled trials and meta-analyses have generally found that carbohydrate restriction outperforms or is equivalent to low-fat and other diets for weight loss, in studies that follow participants for up to two years. To the best of our knowledge, no study has ever shown a low-carb diet to be inferior to any other diet for weight loss.

Meta-analyses and systematic reviews demonstrating low-carb superiority2

International Journal of Endocrinology 2021: Comparing the efficacy and safety of low-carbohydrate diets with low-fat diets for type 2 diabetes mellitus patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials [strong evidence]

This review emphasizes the point that low-carb diets tend to lead to decreased calorie intake, even when people are allowed to eat as much as they want:

Journal of Nutritional Science 2021: Restricting carbohydrates and calories in the treatment of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review of the effectiveness of ‘low-carbohydrate’ interventions with differing energy levels [strong evidence]

Current Diabetes Reports 2021: Efficacy of ketogenic diets on type 2 diabetes: a systematic review [strong evidence]

Nutrients 2020: The effect of low-fat and low-carbohydrate diets on weight loss and lipid levels: a systematic review and meta-analysis [strong evidence]

Nutrients 2020: Impact of a ketogenic diet on metabolic parameters in patients with obesity or overweight and with or without type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials [strong evidence]

The British Journal of Nutrition 2016: Effects of low-carbohydrate diets v. low-fat diets on body weight and cardiovascular risk factors: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials [strong evidence] Learn more

Although the weight loss findings in this meta-analysis were mixed, very low-carb diets (under 50 grams per day) resulted in more fat loss, i.e. better body composition:

Obesity Reviews 2016: Impact of low-carbohydrate diet on body composition: meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies [strong evidence]

This review showed that, in trials specifically designed to assess weight loss, low carb beat low fat. Low fat only led to better weight loss when compared to a “usual diet”:

The Lancet 2015: Effect of low-fat diet interventions versus other diet interventions on long-term weight change in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis [strong evidence]

PLoS One 2015: Dietary intervention for overweight and obese adults: Comparison of low-carbohydrate and low-fat diets. A meta-analysis [strong evidence] Learn more

Obesity Reviews 2012: Systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials of the effects of low carbohydrate diets on cardiovascular risk factors [strong evidence]

Meta-analyses and systematic reviews demonstrating low-carb equivalency3

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2022: Low-carbohydrate versus balanced-carbohydrate diets for reducing weight and cardiovascular risk [strong evidence]

Nutrition and Dietetics 2021: Exploring the highs and lows of very low carbohydrate high fat diets on weight loss and diabetes- and cardiovascular disease-related risk markers: a systematic review [strong evidence]

BMJ 2020: Comparison of dietary macronutrient patterns of 14 popular named dietary programmes for weight and cardiovascular risk factor reduction in adults: systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomised trials [strong evidence]

This review found more weight loss for low carb at the 8-16 week timeframe, but no difference in weight loss for any other timeframe, out to 2 years:

American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2018: Effects of low-carbohydrate- compared with low-fat-diet interventions on metabolic control in people with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review including GRADE assessments [strong evidence]

European Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2018: The interpretation and effect of a low-carbohydrate diet in the management of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials [strong evidence]

Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice 2017: Efficacy of low carbohydrate diet for type 2 diabetes mellitus management: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials [strong evidence]

RCTs demonstrating low-carb superiority

As stated earlier, there isn’t a single RCT that has shown a low-fat or any other diet to result in statistically significant, greater weight loss than low carb. In the following list of clinical trials, low-carb diets resulted in significantly more weight loss than the comparator diet(s).4

PLoS One 2020: Effect of a 90 g/day low-carbohydrate diet on glycaemic control, small, dense low-density lipoprotein and carotid intima-media thickness in type 2 diabetic patients: An 18-month randomised controlled trial [moderate evidence]

Nutrition and Metabolism 2020: Effects of weight loss during a very low carbohydrate diet on specific adipose tissue depots and insulin sensitivity in older adults with obesity: a randomized clinical trial [moderate evidence]

Nutrients 2020: The effects of a low calorie ketogenic diet on glycaemic control variables in hyperinsulinemic overweight/obese females [moderate evidence]

Nutrients 2019: Non-energy-restricted low-carbohydrate diet combined with exercise intervention improved cardiometabolic health in overweight Chinese females [moderate evidence]

Nutrition & Diabetes 2017: Twelve-month outcomes of a randomized trial of a moderate-carbohydrate versus very low-carbohydrate diet in overweight adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus or prediabetes [moderate evidence]

Applied Physiology, Nutrition, and Metabolism 2017: A 12-week low-carbohydrate, high-fat diet improves metabolic health outcomes over a control diet in a randomised controlled trial with overweight defence force personnel [moderate evidence]

Obesity (Silver Spring) 2017: PROP nontaster women lose more weight following a low-carbohydrate versus a low-fat diet in a randomized controlled trial [moderate evidence]

Journal of Medical Internet Research 2017: An online intervention comparing a very low-carbohydrate ketogenic diet and lifestyle recommendations versus a plate method diet in overweight individuals with type 2 diabetes: a randomized controlled trial [moderate evidence]

Diabetes & Metabolic Syndrome 2017: Induced and controlled dietary ketosis as a regulator of obesity and metabolic syndrome pathologies [moderate evidence]

Clinical Nutrition 2017: A randomized controlled trial of 130 g/day low-carbohydrate diet in type 2 diabetes with poor glycemic control [moderate evidence]

Nutrition and Diabetes 2017: Short-term safety, tolerability and efficacy of a very low-calorie-ketogenic diet interventional weight loss program versus hypocaloric diet in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus [moderate evidence]

The Journal of Nutrition 2015: A lower-carbohydrate, higher-fat diet reduces abdominal and intermuscular fat and increases insulin sensitivity in adults at risk of type 2 diabet [moderate evidence]

In this one-year study, 148 people were randomized to consume a low-carb diet (less than 40 grams of carbohydrate per day) or a low-fat diet (less than 30% of energy from fat per day). In addition to losing 3.5 kg (7.7 lbs) more than the low-fat group, the low-carb group also had greater improvements in high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, triglycerides (TG), and other cardiovascular disease risk factors:

Annals of Internal Medicine 2014: Effects of low-carbohydrate and low-fat diets: a randomized trial [moderate evidence]

PloS One 2014: A randomized pilot trial of a moderate carbohydrate diet compared to a very low carbohydrate diet in overweight or obese individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus or prediabetes [moderate evidence]

Journal of Pediatric Endocrinology and Metabolism 2012: Metabolic impact of a ketogenic diet compared to a hypocaloric diet in obese children and adolescents [moderate evidence]

Obesity (Silver Spring) 2011: Adiponectin changes in relation to the macronutrient composition of a weight-loss diet [moderate evidence]

The Journal of Pediatrics 2010: Efficacy and safety of a high protein, low carbohydrate diet for weight loss in severely obese adolescents [moderate evidence]

Lipids 2009: Carbohydrate restriction has a more favorable impact on the metabolic syndrome than a low fat diet [moderate evidence]

Obesity 2009: Effects of a low carbohydrate weight loss diet on exercise capacity and tolerance in obese subjects [moderate evidence]

In this two-year trial, 322 people were randomly assigned to follow a Mediterranean, low-fat, or low-carb diet. The low-carb group lost the most weight, even though they were allowed to eat until satisfied; the other two groups followed calorie-restricted diets:

New England Journal of Medicine 2008: Weight loss with a low-carbohydrate, Mediterranean, or low-fat diet [moderate evidence]

The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2008: Effects of weight loss from a very-low-carbohydrate diet on endothelial function and markers of cardiovascular disease risk in subjects with abdominal obesity [moderate evidence]

Nutrition & Metabolism 2008: The effect of a low-carbohydrate, ketogenic diet versus a low-glycemic-index diet on glycemic control in type 2 diabetes mellitus [moderate evidence]

Diabetic Medicine 2007: A low-carbohydrate diet is more effective in reducing body weight than healthy eating in both diabetic and non-diabetic subjects [moderate evidence]

American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2007: Low- and high-carbohydrate weight-loss diets have similar effects on mood [moderate evidence]

One of the best-known weight-loss trials (often referred to as the A to Z study) randomized overweight premenopausal women to a low-carb (Atkins); moderate-carb (Zone); low-fat (Ornish); or low-calorie, portion-controlled (LEARN) diet for one year. The women in the low-carb group lost twice as much weight (4.7 kg, or 10.3 lbs) as the Ornish and LEARN groups and nearly three times as much as the women in the Zone group:

Journal of the American Medical Association 2007: Comparison of the Atkins, Zone, Ornish, and LEARN diets for change in weight and related risk factors among overweight premenopausal women. The A to Z weight loss study: a randomized trial [moderate evidence]

Diabetic Medicine 2006: Short-term effects of severe dietary carbohydrate-restriction advice in Type 2 diabetes–a randomized controlled trial [moderate evidence]

Journal of the American Dietetic Association 2005: Perceived hunger is lower and weight loss is greater in overweight premenopausal women consuming a low-carbohydrate/high-protein vs high carbohydrate/low-fat diet [moderate evidence]

Diabetologia 2005: Comparison of high-fat and high-protein diets with high-carbohydrate diet in insulin-resistant obese women [moderate evidence]

The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 2005: The role of energy expenditure in the differential weight loss in obese women on low-fat and low-carbohydrate diets [moderate evidence]

Archives of Internal Medicine 2004: The national cholesterol education program diet vs a diet lower in carbohydrates and higher in protein and monounsaturated fat. A randomized trial [moderate evidence]

Nutrition & Metabolism 2004: Comparison of energy-restricted very low-carbohydrate and low-fat diets on weight loss and body composition in overweight men and women [moderate evidence]

Annals of Internal Medicine 2004: A low-carbohydrate, ketogenic diet versus a low-fat diet to treat obesity and hyperlipidemia. A randomized, controlled trial [moderate evidence]

The Journal of Nutrition 2004: Very low-carbohydrate and low-fat diets affect fasting lipids and postprandial lipemia differently in overweight men [moderate evidence]

The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 2003: A randomized trial comparing a very low carbohydrate diet and a calorie-restricted low fat diet on body weight and cardiovascular risk factors in healthy women [moderate evidence]

The New England Journal of Medicine 2003: A low-carbohydrate as compared with a low-fat diet in severe obesity [moderate evidence]

The Journal of Pediatrics 2003: Effects of a low-carbohydrate diet on weight loss and cardiovascular risk factor in overweight adolescents [moderate evidence]

RCTs demonstrating low-carb equivalency

European Journal of Nutrition 2021: Effects of very low-carbohydrate vs. high-carbohydrate weight loss diets on psychological health in adults with obesity and type 2 diabetes: a 2-year randomized controlled trial [moderate evidence]

Diabetes, Obesity, and Metabolism 2018: Effects of an energy-restricted low-carbohydrate, high unsaturated fat/low saturated fat diet versus a high-carbohydrate, low-fat diet in type 2 diabetes: A 2-year randomized clinical trial [moderate evidence]

This 12-month study found that people who followed a low-carb or low-fat diet (both with low amounts of sugar or processed carbohydrates) lost similar amounts of weight, regardless of whether the diet “matched” their genetic predisposition to metabolize fats or carbs more effectively:

Journal of the American Medical Association 2018: Effect of low-fat vs low-carbohydrate diet on 12-month weight loss in overweight adults and the association with genotype pattern or insulin secretion: the DIETFITS randomized clinical trial [moderate evidence]

American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2017: Dynamics of intrapericardial and extrapericardial fat tissues during long-term, dietary-induced, moderate weight loss [moderate evidence]

American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2017: Visceral adiposity and metabolic syndrome after very high-fat and low-fat isocaloric diets: a randomized controlled trial [moderate evidence]

Obesity 2016: Weight loss on low-fat vs. low-carbohydrate diets by insulin resistance status among overweight adults and adults with obesity: A randomized pilot trial [moderate evidence]

In this one-year trial of people with type 2 diabetes, both low-carbohydrate and high-carbohydrate diets led to similar weight loss of about 10 kg (22 pounds):

The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2015: Comparison of low- and high-carbohydrate diets for type 2 diabetes management: a randomized trial [moderate evidence]

Diabetes/Metabolism Research and Reviews 2012: Evaluation of weight loss and adipocytokines levels after two hypocaloric diets with different macronutrient distribution in obese subjects with rs9939609 gene variant [moderate evidence]

Journal of Pediatric Endocrinology and Metabolism 2012: Metabolic impact of a ketogenic diet compared to a hypocaloric diet in obese children and adolescents [moderate evidence]

Nutrition, Metabolism, and Cardiovascular Diseases 2010: Long-term effects of a low carbohydrate, low fat or high unsaturated fat diet compared to a no-intervention control [moderate evidence]

Interestingly, two years before the A to Z study showed that low carb was clearly more effective for weight loss than other diets, a similar study found that weight loss was roughly the same after one year for each of the four diets studied: low-carb, low-fat, Weight Watchers, or Zone:

Journal of the American Medical Association 2005: Comparison of the Atkins, Ornish, Weight Watchers, and Zone Diets for weight loss and heart disease risk reduction [moderate evidence]

There are many more RCTs showing low-carb to be equivalent to other dietary strategies. The UK Public Health Collaboration website does a great job of collating these trials.

Learn more

Protein on a low-carb or keto diet

Metabolic risk factors

Low-carb diets can improve all the main features of metabolic syndrome: abdominal obesity, high blood sugar, high blood pressure (BP), low HDL-cholesterol, and high triglycerides (TG). Given that these metabolic risk factors are strongly linked to chronic diseases like type 2 diabetes, heart disease, stroke, dementia, and cancer, low-carb nutrition should be considered an important preventive tool.5

Meta-analyses6

All meta-analyses of RCTs have found that low-carb diets are either superior or equivalent to low-fat diets for improving all the metabolic risk factors listed above. With respect to LDL-cholesterol, some meta-analyses have found low carb to be equivalent to low fat, while others have found that low fat does a better job of lowering LDL.7

This meta-analysis of 8 RCTs found that a very low-carb ketogenic diet was superior for raising HDL and lowering TG:

Nutrition Reviews 2022: Effect of a very low-carbohydrate ketogenic diet vs recommended diets in patients with type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis [strong evidence]

Unlike most earlier meta-analyses that tend to favor low carb, this systematic review of 61 RCTs found that there is likely no difference between low-carb and balanced-carb diets on cardiovascular risk markers, with up to two years of dietary intervention:

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2022: Low-carbohydrate versus balanced-carbohydrate diets for reducing weight and cardiovascular risk [strong evidence]

This included 11 RCTs, finding that low carb was better at raising HDL, while the two diets performed the same for reducing LDL:

European Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2022: The effects of low-fat, high-carbohydrate diets vs. low-carbohydrate, high-fat diets on weight, blood pressure, serum lipids and blood glucose: a systematic review and meta-analysis [strong evidence]

This included 12 RCTs, finding that low carb was superior for lowering TG and increasing HDL:

International Journal of Endocrinology 2021: Comparing the efficacy and safety of low-carbohydrate diets with low-fat diets for type 2 diabetes mellitus patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials [strong evidence]

This unique meta-analysis included 38 RCTs and found that low-carb diets increased peak LDL particle size and reduced LDL particle number; part of low carb’s ability to shift LDL size from small to large was attributable to differences in weight loss between the diets. However, there was no statistically significant effect of low carb on mean LDL particle size:

American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2021: Effect of carbohydrate-restricted dietary interventions on LDL particle size and number in adults in the context of weight loss or weight maintenance: a systematic review and meta-analysis [strong evidence]

This systematic review included 8 RCTs, finding that low carb more effectively lowered TG and raised HDL, while low fat was better at lowering LDL:

Nutrition and Dietetics 2021: Exploring the highs and lows of very low carbohydrate high fat diets on weight loss and diabetes- and cardiovascular disease-related risk markers: a systematic review [strong evidence]

This included 38 RCTs, finding low carb to be better at reducing TG and raising HDL, while low fat was better at reducing LDL:

Nutrients 2020: The effect of low-fat and low-carbohydrate diets on weight loss and lipid levels: a systematic review and meta-analysis [strong evidence]

This included 14 RCTs, finding that ketogenic diets were better at reducing TG and raising HDL compared to low-fat diets:

Nutrients 2020: Impact of a ketogenic diet on metabolic parameters in patients with obesity or overweight and with or without type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials [strong evidence]

This included 12 RCTs and found low-carb diets led to a decrease in TG and BP, with an increase in HDL and LDL:

PLoS One 2020: The effects of low-carbohydrate diets on cardiovascular risk factors: A meta-analysis [strong evidence]

This included 8 RCTs, finding that low carb was better than low fat for raising HDL and lowering TG, without significantly raising LDL:

Nutrition Reviews 2019: Effects of carbohydrate-restricted diets on low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels in overweight and obese adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis [strong evidence]

This included 18 RCTs and found that low carb was better for reducing HbA1c, TG, and systolic BP, while raising HDL, with no effect on LDL:

European Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2017: The interpretation and effect of a low-carbohydrate diet in the management of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials [strong evidence]

This included 11 RCTs, finding that low-carb diets led to greater weight loss, lower TG, and higher HDL compared to low-fat diets. LDL, however, increased on low carb:

British Journal of Nutrition 2016: Effects of low-carbohydrate diets v. low-fat diets on body weight and cardiovascular risk factors: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials

[strong evidence]

This included 17 trials of low carb vs. low fat and found that low carb led to lower TG and higher HDL, but also higher LDL:

PLoS One 2015: Dietary Intervention for Overweight and Obese Adults: Comparison of Low-Carbohydrate and Low-Fat Diets. A Meta-Analysis [strong evidence]

This included 13 RCTs, finding low carb to be better than low fat for increasing HDL and reducing TG and systolic BP. Interestingly, there was a higher attrition rate in the low-fat group, suggesting a patient preference for low-carb/high-protein over low-fat/high-carb:

Obesity Reviews 2009: Systematic review of randomized controlled trials of low-carbohydrate vs. low-fat/low-calorie diets in the management of obesity and its comorbidities [strong evidence]

This included 5 RCTs of low-carb vs. low-fat diets, finding that low carb was superior for raising HDL and lowering TG, while low fat was superior for lowering LDL:

Archives of Internal Medicine 2006: Effects of low-carbohydrate vs low-fat diets on weight loss and cardiovascular risk factors: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials [strong evidence]

Randomized controlled trials

This RCT showed that low carb better reduced HgbA1c, with no differential effect on lipids between groups:

Diabetes, Obesity, and Metabolism 2022: Effects of a 6-month, low-carbohydrate diet on glycaemic control, body composition, and cardiovascular risk factors in patients with type 2 diabetes: An open-label randomized controlled trial [moderate evidence]

This RCT kept protein constant across the three study groups and showed improvements in TG, HDL, and Lp(a) with low carb/high fat:

American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2022: Effects of a low-carbohydrate diet on insulin-resistant dyslipoproteinemia — a randomized controlled feeding trial [moderate evidence]

This 18-month trial found low carb was better at reducing HgbA1c and blood pressure, but there was no difference in lipids:

PLos One 2020: Effect of a 90 g/day low-carbohydrate diet on glycaemic control, small, dense low-density lipoprotein and carotid intima-media thickness in type 2 diabetic patients: An 18-month randomised controlled trial [moderate evidence]

This trial was designed to keep weight stable, to remove it as a variable. Low carb was still better at lowering TG, increasing HDL, and shifting LDL size from small to large. Despite being 2.5x higher in saturated fat, the low-carb diet actually reduced plasma levels of saturated fat:

JCI Insight 2019: Dietary carbohydrate restriction improves metabolic syndrome independent of weight loss [randomized trial; moderate evidence]

DIETFITS study compared 30% carb vs 48% carbs. The low-carb group had a greater reduction in TG and increase in HDL:

JAMA 2018: Effect of Low-Fat vs Low-Carbohydrate Diet on 12-Month Weight Loss in Overweight Adults and the Association With Genotype Pattern or Insulin Secretion: The DIETFITS Randomized Clinical Trial [moderate evidence]

This was a 12 month RCT of a low-carb diet (20-50g carbs) vs a diet with 45-50% carbs. Low carb showed TG decreased 10mg/dl, compared to an increase in control, and HDL was also better for low carb:

Nutrition and Diabetes 2017: Twelve-month outcomes of a randomized trial of a moderate-carbohydrate versus very low-carbohydrate diet in overweight adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus or prediabetes [moderate evidence]

This trial compared 14% carbs vs 53% carbs. Low carb was better for glycemic variability, TG reduction and HDL increase:

American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2015: Comparison of low- and high-carbohydrate diets for type 2 diabetes management: a randomized trial [moderate evidence]

This RCT compared a diet of <40g carbs to a low-fat diet with <30% fat. Low carb was better for TG and HDL: Annals of Internal Medicine 2014: Effects of low-carbohydrate and low-fat diets: a randomized trial [moderate evidence]

This RCT compared a diet with 57g of carbs vs 138g. Greater carb reduction improved TG, glucose and insulin levels:

PLoS One 2014: A randomized pilot trial of a moderate carbohydrate diet compared to a very low carbohydrate diet in overweight or obese individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus or prediabetes [moderate evidence]

This RCT compared calorie restriction vs low carb. Low carb was better for A1c and TG:

Internal Medicine 2014: A non-calorie-restricted low-carbohydrate diet is effective as an alternative therapy for patients with type 2 diabetes [randomized trial; moderate evidence]

This trial compared 40g carbs vs 200g. Low carb was better for TG, HDL, and systolic BP:

Metabolism 2013: Consuming a hypocaloric high fat low carbohydrate diet for 12 weeks lowers C-reactive protein, and raises serum adiponectin and high density lipoprotein-cholesterol in obese subjects [randomized trial; moderate evidence]

Learn more

How to normalize your blood pressure naturally

Cholesterol and low-carb diets

Is elevated LDL cholesterol harmful?

How to treat insulin resistance

How to improve and measure your body composition

Heart disease

Low-carbohydrate and ketogenic diets usually contain more saturated fat than the typical low-fat diet that has been recommended for decades. This has led many to express concern that low-carb diets might increase the risk of heart attacks and other forms of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease.

But when we look critically for evidence of a causal link between saturated fat and heart disease, we find weak and inconsistent data. Although some reviews of the overall medical literature have found a weak correlation, an increasing number of meta-analyses and systematic reviews of randomized trials are finding that there is no significant connection between saturated fat and heart disease.

The authors of one review article concluded: “The preponderance of evidence indicates that low-fat diets that reduce serum cholesterol do not reduce cardiovascular events or mortality. Specifically, diets that replace saturated fat with polyunsaturated fat do not convincingly reduce cardiovascular events or mortality. These conclusions stand in contrast to current opinion.”8

Another review of the evidence linking saturated fat to heart disease, written by four prominent experts, noted that when any fat — including saturated fat – replaces carbohydrate in the diet, there is improvement in important lipid markers related to risk of heart disease.9

As a result, some world experts have been calling for a shift in focus – away from restricting total saturated fat intake – and towards the quality of food that we eat, recognizing that natural saturated fats in whole foods like meat, fish, and dairy are likely to behave differently in the body when compared to the fats found in pastries and processed foods.10

Meta-analyses of RCTs11

A 2020 Cochrane review of RCTs showed a modest reduction in cardiovascular events for lower saturated fat intake. But it found no benefit to lowering saturated fat intake for heart attack, stroke, cardiovascular death, or all-cause death:12

Cochrane Database of Systemic Reviews 2020: Reduction in saturated fat intake for cardiovascular disease [systematic review of randomized trials; strong evidence]

The following four meta-analyses of RCTs found no reduction in heart disease risk as a result of replacing saturated fats with unsaturated fats. The first one specifically noted that earlier meta-analyses that found an effect did so because they included inadequately controlled trials:

Nutrition Journal 2017: The effect of replacing saturated fat with mostly n-6 polyunsaturated fat on coronary heart disease: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials [strong evidence]

Open Heart 2016: Evidence from randomised controlled trials does not support current dietary fat guidelines: a systematic review and meta-analysis [strong evidence]

Annals of Internal Medicine 2014: Association of dietary, circulating, and supplement fatty acids with coronary risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis [strong evidence for the RCT portion of this meta-analysis]

British Medical Journal 2013: Dietary fatty acids in the secondary prevention of coronary heart disease: a systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regression [strong evidence]

This review found that reducing or modifying dietary fat intake reduced the risk of heart attack and other cardiovascular events by 14 percent. The reduction in risk was seen only in studies of at least two years duration and only in men; there was no effect on total or heart disease mortality:

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2011: Reduced or modified dietary fat for preventing cardiovascular disease [meta-analysis of RCTs; strong evidence]

This review found that substituting polyunsaturated fats for saturated fats led to a 19 percent reduction in coronary events:

PloS Med 2010: Effects on coronary heart disease of increasing polyunsaturated fat in place of saturated fat: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials [strong evidence]

Meta-analyses of observational studies

Remember that observational studies cannot prove causality, and any associations they do find may be confounded by a myriad of measured and unmeasured variables. Therefore, unless the relative risk of a finding is greater than 2, we consider this very weak evidence.

This review found that “[d]iets high in saturated fat were associated with higher mortality from all-causes, CVD, and cancer, whereas diets high in polyunsaturated fat were associated with lower mortality from all-causes, CVD, and cancer.” But the relative risks were tiny, on average about 1.05:

Clinical Nutrition 2021: Association between dietary fat intake and mortality from all-causes, cardiovascular disease, and cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies [very weak evidence]

This meta-analysis found that, among all types of dietary fat, only trans fatty acids were associated with the risk of cardiovascular disease. Polyunsaturated fats were found to be cardioprotective only in studies that followed subjects for more than ten years:

Lipids in Health and Disease 2019: Dietary total fat, fatty acids intake, and risk of cardiovascular disease: a dose-response meta-analysis of cohort studies [very weak evidence]

These two meta-analyses of observational studies reached the same conclusion about the lack of association between saturated fat and heart disease:

British Journal of Sports Medicine 2017: Evidence from prospective cohort studies does not support current dietary fat guidelines: a systematic review and meta-analysis [very weak evidence]

British Medical Journal 2015: Intake of saturated and trans unsaturated fatty acids and risk of all cause mortality, cardiovascular disease, and type 2 diabetes: systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies [very weak evidence]

This systematic review concluded that “…observational evidence does not support the hypothesis that dairy fat or high-fat dairy foods contribute to obesity or cardiometabolic risk…”:

European Journal of Nutrition 2012: The relationship between high-fat dairy consumption and obesity, cardiovascular, and metabolic disease [very weak evidence]

Similarly, a 2010 review of cohort studies found “…no significant evidence for concluding that dietary saturated fat is associated with an increased risk of CHD or CVD…”:

The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2010: Meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies evaluating the association of saturated fat with cardiovascular disease [very weak evidence]

This review also found that saturated fat did not correlate with heart disease risk:

Archives of Internal Medicine 2009: A systematic review of the evidence supporting a causal link between dietary factors and coronary heart disease [very weak evidence]

Randomized controlled trials of hard endpoints

Following are some of the largest and longest clinical trials that have examined the link between dietary fat and heart disease, stroke, and death.

In the Women’s Health Initiative trial, the group randomized to a low-fat diet did not show a reduction in heart attacks or strokes:

JAMA 2006: Low-fat dietary pattern and risk of cardiovascular disease: the Women’s Health Initiative randomized controlled dietary modification trial [moderate evidence]

In the Minnesota Coronary Survey, participants were randomized to one of two diets that had the same percentage of total fat. The control diet had more saturated fat, while the intervention diet had more polyunsaturated fat. While cholesterol levels fell lower in the intervention group, there were no differences between groups in cardiovascular events, cardiovascular mortality, or total mortality:

Arteriosclerosis 1989: Test of effect of lipid lowering by diet on cardiovascular risk. The Minnesota Coronary Survey [randomized controlled trial; moderate evidence]

In the Multifactor Primary Prevention Trial in Sweden, both the intervention group and the control group showed improvements in risk factors such as blood pressure, lipids, and smoking. There were no differences in heart events, strokes, or mortality of any kind:

European Heart Journal 1986: The multifactor primary prevention trial in Göteborg, Sweden [randomized controlled trial; moderate evidence]

The Helsinki Businessmen Study was originally designed as a 5-year intervention trial, but it has continued as a prospective observational study and continues to report on the original study subjects. At the end of the 5-year trial, the intervention group (diet counseling + lipid/BP lowering) showed a decreased risk of stroke but an increased risk of heart disease, as compared to the control group (no treatment at all). Over the long term, the intervention group has been shown to have increased total and cardiovascular mortality:13

JAMA 1985: Multifactorial primary prevention of cardiovascular diseases in middle-aged men. Risk factor changes, incidence, and mortality [randomized controlled trial; moderate evidence]

The MRFIT trial enrolled men at high risk for a first cardiac event. The intervention group received more than just dietary advice; they also received focused attention to their blood pressure and smoking habits. There was no difference between the groups with respect to cardiovascular or total mortality:

JAMA 1982: Multiple risk factor intervention trial. Risk factor changes and mortality results. Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial Research Group [randomized controlled trial; moderate evidence]

In the LA Veterans Trial, the intervention group received a diet that was higher in vegetable oil (unsaturated fat), and they did show a reduction in cardiovascular mortality, compared to the control group eating more saturated fat in the form of dairy. But the intervention group also showed increased mortality due to cancer. Further, the control group contained more heavy smokers, and many meals were eaten outside the institution where the men lived:

Circulation 1969: A controlled clinical trial of a diet high in unsaturated fat in preventing complications of atherosclerosis [moderate evidence]

The Medical Research Council of London’s study found that men with a prior heart attack, randomized to a low-saturated fat diet with soybean oil or their regular diet, showed no difference in future heart attacks, cardiovascular mortality, or total mortality:

Lancet 1968: Controlled trial of soya-bean oil in myocardial infarction [moderate evidence]

In the Oslo Diet-Heart study, men who had previously had a heart attack were randomized to a low-fat or control diet. Men in the low-fat group reduced their cholesterol and showed a reduction in both non-fatal and fatal heart attacks:

Acta Medica Scandinavica Supplementum 1966: The effect of plasma cholesterol lowering diet in male survivors of myocardial infarction. A controlled clinical trial [moderate evidence]

Randomized controlled trials of surrogate endpoints

It is significantly more challenging to study hard endpoints like heart attacks, strokes, and death, as compared to surrogate endpoints like the amount of plaque in arteries. Hard endpoint studies, like the ones in the section above, require larger numbers of people and longer periods of time. That said, some surrogate endpoints may be better than others at predicting hard endpoints. Following are a few trials that examined such endpoints.

This trial showed no difference in carotid IMT between a low-carb diet and a traditional diabetes diet for those with type 2 diabetes:

PLos One 2020: Effect of a 90 g/day low-carbohydrate diet on glycaemic control, small, dense low-density lipoprotein and carotid intima-media thickness in type 2 diabetic patients: An 18-month randomised controlled trial [moderate evidence]

This trial found that there was no change in vascular endothelial function, whether randomized to a low-carb, low-saturated fat diet or a high-carb, low-fat diet:

Atherosclerosis 2016: Long-term effects of weight loss with a very-low carbohydrate, low saturated fat diet on flow mediated dilatation in patients with type 2 diabetes: A randomised controlled trial [moderate evidence]

This RCT tracked signs of carotid atherosclerosis during two years of advice to eat a low-carb, high-fat diet; low-fat diet; or Mediterranean diet. There was significant regression of carotid vessel wall volume seen in all three diet groups, implying a reduction of atherosclerosis. One possible explanation, according to the researchers, weight loss-induced reduction in blood pressure resulting from the diets:

Circulation 2010: Dietary intervention to reverse carotid atherosclerosis [moderate evidence]

This trial found that a low-fat diet was better than a low-carb diet for improving vascular endothelial function in obese subjects. Unfortunately, this small study had 8 dropouts in the low-carb group vs none in the low-fat group. In addition, the subjects in the low-carb group skewed younger and male, potentially affecting the results.14

Hypertension 2008: Benefit of low-fat over low-carbohydrate diet on endothelial health in obesity [moderate evidence]

Learn more

Vegetable oils: Are they healthy?

“Healthy” whole grains: What the evidence really shows

Cholesterol and low-carb diets

Is elevated LDL cholesterol harmful?

Guide to red meat: Is it healthy?

The Nutrition Coalition: The disputed science on saturated fats

Low-carb videos

Fats, cholesterol and dietary guidelines

Type 2 diabetes

In 2019, the American Diabetes Association (ADA) stated that reducing carbohydrate intake is the most effective nutritional strategy for improving blood sugar control in those with diabetes.15

This statement is based on numerous randomized controlled trials and meta-analyses of such trials supporting the use of a low-carb diet in the treatment of type 2 diabetes.

Meta-analyses

Nutrition Reviews 2022: Effect of a very low-carbohydrate ketogenic diet vs recommended diets in patients with type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis [strong evidence]

International Journal of Endocrinology 2021: Comparing the efficacy and safety of low-carbohydrate diets with low-fat diets for type 2 diabetes mellitus patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials [strong evidence]

Journal of Nutritional Science 2021: Restricting carbohydrates and calories in the treatment of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review of the effectiveness of ‘low-carbohydrate’ interventions with differing energy levels [strong evidence]

The following paper found that low carb shows significant benefit at 6 months that disappears by 12 months. However, even meta-analyses of RCTs can have issues with scientific quality as we explained in our post about this publication:

BMJ 2021: Efficacy and safety of low and very low carbohydrate diets for type 2 diabetes remission: systematic review and meta-analysis of published and unpublished randomized trial data [strong evidence]

Nutrients 2020: Impact of a ketogenic diet on metabolic parameters in patients with obesity or overweight and with or without type 2 diabetes: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials [strong evidence]

Diabetes, Obesity & Metabolism 2019: An evidence‐based approach to developing low‐carbohydrate diets for type 2 diabetes management: a systematic review of interventions and methods [strong evidence]

Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice 2018: Effect of dietary carbohydrate restriction on glycemic control in adults with diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis [strong evidence]

The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2018: Effects of low-carbohydrate- compared with low-fat-diet interventions on metabolic control in people with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review including GRADE assessments [strong evidence]

BMJ Open Diabetes Research and Care 2017: Systematic review and meta-analysis of dietary carbohydrate restriction in patients with type 2 diabetes [strong evidence]

European Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2017: The interpretation and effect of a low-carbohydrate diet in the management of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials [strong evidence]

Randomized controlled trials

The following RCTs demonstrate the benefits of low-carbohydrate diets in people with type 2 diabetes.

Diabetes, Obesity, and Metabolism 2022: Effects of a 6-month, low-carbohydrate diet on glycaemic control, body composition, and cardiovascular risk factors in patients with type 2 diabetes: An open-label randomized controlled trial [moderate evidence]

PLos One 2021: Safety and efficacy of very low carbohydrate diet in patients with diabetic kidney disease — a randomized controlled trial [moderate evidence]

Frontiers in Endocrinology 2021: A low-carbohydrate diet realizes medication withdrawal: a possible opportunity for effective glycemic control [randomized controlled trial; moderate evidence]

PLos One 2020: Effect of a 90 g/day low-carbohydrate diet on glycaemic control, small, dense low-density lipoprotein and carotid intima-media thickness in type 2 diabetic patients: An 18-month randomised controlled trial [moderate evidence]

Nutrients 2018: The effect of low-carbohydrate diet on glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes [randomized controlled trial; moderate evidence]

Nutrition & Diabetes 2017: Twelve-month outcomes of a randomized trial of a moderate-carbohydrate versus very low-carbohydrate diet in overweight adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus or prediabetes [moderate evidence]

Diabetes Care 2014: A very low-carbohydrate, low–saturated fat diet for type 2 diabetes management: a randomized trial [moderate evidence]

Nutrition & Metabolism 2008: The effect of a low-carbohydrate, ketogenic diet versus a low-glycemic index diet on glycemic control in type 2 diabetes mellitus [randomized controlled trial; moderate evidence]

Non-randomized trials

Although randomized controlled trials represent a stronger level of evidence, there are a few notable non-randomized studies on this subject.

A study of a ketogenic, low-carbohydrate diet performed by Virta Health and involving about 330 people with diabetes found that, at the one-year mark, 97 percent of the participants had reduced or stopped their insulin use. Furthermore, 58 percent no longer met the criteria for a diagnosis of diabetes; in other words, they had reversed their disease.16

Frontiers in Endocrinology 2019: Long-term effects of a novel continuous remote care intervention including nutritional ketosis for the management of type 2 diabetes: A 2-year non-randomized clinical trial [weak evidence]

Diabetes Therapy 2018: Effectiveness and safety of a novel care model for the management of type 2 diabetes at 1 year: an open-label, non-randomized, controlled study [weak evidence]

The longest published study on low carb for type 2 diabetes is a non-randomized intervention trial that compared a 20% carbohydrate diet (daily intake of carbohydrate was 80-90 grams) to usual care. Although the study was quite small, with only 23 participants in the final low-carb group, a follow-up assessment at 44 months showed continued improvement in HbA1c, weight, and reduction of diabetes medications:

Nutrition & Metabolism 2008: Low-carbohydrate diet in type 2 diabetes: stable improvement of bodyweight and glycemic control during 44 months follow-up [retrospective follow-up of non-randomized study; very weak evidence]

Prediabetes

A two-year nonrandomized trial of a ketogenic diet run by Virta Health demonstrated blood sugar normalization in over 50% of participants with prediabetes.

Nutrients 2021: Type 2 Diabetes Prevention Focused on Normalization of Glycemia: A Two-Year Pilot Study [nonrandomized study, weak evidence]

Learn more

Low-carb videos

Type 2 diabetes

Type 1 diabetes

Compared with the robust evidence base supporting low-carb and ketogenic diets for type 2 diabetes, research on carb restriction for type 1 diabetes is greatly lacking. Although low carb and keto are still considered controversial in the management of type 1 diabetes, the results from some existing studies are encouraging.

Meta-analyses

To date, there is only one systematic review examining low-carbohydrate diets in type 1 diabetes. Only nine studies qualified for inclusion in the review, and only two of those were RCTs. Because of the heterogeneity of the studies, no firm conclusions could be drawn about the utility and safety of low-carb diets in type 1 diabetes. The authors concluded that there is an urgent need for randomized controlled trials in this area:

PLOS One 2018: Low-carbohydrate diets for type 1 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review [weak evidence]17

Randomized controlled trials

Controlled studies have shown that people with type 1 diabetes who limit carbs to 50 to 100 grams per day experience more stable blood sugar and fewer episodes of hypoglycemia compared to people with type 1 who eat higher-carb diets — with a bonus of increased weight loss in those who are overweight:

Diabetes, Obesity and Metabolism 2021: The beneficial short-term effects of a high-protein/low-carbohydrate diet on glycaemic control assessed by continuous glucose monitoring in patients with type 1 diabetes [randomized controlled trial; moderate evidence]

Diabetes, Obesity and Metabolism 2019: Low versus high carbohydrate diet in type 1 diabetes: a 12-week randomized open-label crossover study [moderate evidence]

Learn more

Diabetes, Obesity and Metabolism 2017: Short-term effects of a low-carbohydrate diet on glycaemic variables and cardiovascular risk markers in patients with type 1 diabetes: a randomized open-label crossover trial [moderate evidence]

Asia Pacific Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2016: A randomised trial of the feasibility of a low-carbohydrate diet vs standard carbohydrate counting in adults with type 1 diabetes taking body weight into account [moderate evidence]

Non-controlled and observational studies

Some non-controlled and observational studies, while considered weak and very weak evidence, respectively, demonstrate excellent “real world” results for people with type 1 diabetes who follow a low-carbohydrate diet.

This observational study reported results from a survey completed by 316 people with type 1 diabetes or parents of children with type 1 diabetes who consumed roughly 30 grams of carbs per day. The group reported exceptional blood glucose control with infrequent hypoglycemic episodes and an average HbA1c of 5.67% (39 mmol/mol). Children who followed a carbohydrate-reduced diet did not show any signs of impaired growth, although the duration of time on diet was short (1.2 +/- 0.8 years):

Learn more

Pediatrics 2018: Management of type 1 diabetes with a very low–carbohydrate diet [survey data; very weak evidence]

In addition, a group of Swedish doctors reported that their patients with type 1 diabetes who followed a low-carbohydrate diet consistently had significant improvements in blood sugar, HbA1c, and reduction in hypoglycemia after one year. These effects persisted after four years in patients who stayed on the diet:

Diabetology & Metabolic Syndrome 2012: Low-carbohydrate diet in type 1 diabetes, long-term improvement and adherence: a clinical audit [non-controlled study; weak evidence]

Upsala Journal of Medical Sciences 2005: A low-carbohydrate diet in type 1 diabetes: clinical experience – a brief report [non-controlled study; weak evidence]

Learn more

Type 1 diabetes – how to control your blood sugar with fewer carbs

Low-carb videos

Type 1 diabetes

Long-term safety of low carb

Some health experts have raised concerns about the long-term effects of low carb. All diets can be done well or poorly, and a risk of nutritional inadequacy exists with all ways of eating. However, a well-planned, nutritionally adequate low-carb diet has not shown evidence of risk, to the best of our knowledge, as dietary carbohydrate is not an essential nutrient.

Bone health

Some concerns have been raised about the perceived risks of protein intake on the acid-base balance of the body and how that could affect bones. No evidence supports this concern. The internal pH of the body is firmly regulated and is not significantly affected by diet.18

The International Osteoporosis Foundation published a narrative review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses, concluding: “There is no evidence that diet-derived acid load is deleterious for bone health. Thus, insufficient dietary protein intakes may be a more severe problem than protein excess in the elderly.”19

Meta-analyses

A meta-analysis of RCTs and cohort studies concluded that higher protein intake isn’t harmful for bone health and may even be beneficial for preventing bone loss:

The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2017: Dietary protein and bone health: a systematic review and meta-analysis from the National Osteoporosis Foundation [moderate evidence]

This meta-analysis of nutritional epidemiology studies showed that higher protein consumption can decrease the risk of hip fracture. There was no differential risk between animal vs vegetable protein:

Scientific Reports 2015: The relationship between dietary protein consumption and risk of fracture: a subgroup and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies [very weak evidence]

Randomized controlled trials

Finally, three controlled trials show that low-carb is safe for bones, even when followed for up to two years:

Nutrition 2016: Long-term effects of a very-low-carbohydrate weight-loss diet and an isocaloric low-fat diet on bone health in obese adults [moderate evidence]

Annals of Internal Medicine 2010: Weight and metabolic outcomes after 2 years on a low-carbohydrate versus low-fat diet: a randomized trial [moderate evidence]

The Journal of Pediatrics 2010: Efficacy and safety of a high protein, low carbohydrate diet for weight loss in severely obese adolescents [moderate evidence]

The above evidence against harm is far stronger than the evidence suggesting harm, as we detail in a news post about a study showing increased markers of bone turnover after 3 weeks on a keto diet in highly trained race walkers.

Learn more

Top 17 low carb & keto controversies

How to improve your bone health

Kidney health

Concerns have been raised about whether low-carb and ketogenic diets may increase the risk of kidney stones, as well as whether they can cause impaired filtering function (reduced glomerular filtration rate). While the mechanisms by which low carb can increase kidney stones are more speculative, it is specifically the perception that low-carb diets contain more protein that concerns researchers, given that people with moderate-severe kidney disease are advised to restrict protein to slow the progression of disease.

Meta-analyses

This meta-analysis of clinical trials and observational studies reported a pooled incidence of kidney stones at 5.6% after 4 years on a ketogenic diet. Compared to the kidney stone incidence in the general population of 0.3% per year for men and 0.25% per year for women, it seems that ketogenic diets do increase the risk:

Diseases 2021: Incidence and characteristics of kidney stones in patients on ketogenic diet: a systematic review and meta-analysis [moderate evidence]

This meta-analysis of RCTs examining stage 1-3 diabetic kidney disease showed that restricting protein intake to < 0.8 g/kg/day did confer protective benefits on kidney function. It should be noted that the strength of the authors’ conclusions are somewhat diminished by the trials’ low quality, small sizes, and heterogeneity of study populations. Nonetheless, this does serve as a reminder that the data regarding the safety of low-carb diets in early-stage kidney disease should not be considered to be conclusive:

Diabetes Therapy 2021: Diabetic kidney disease benefits from intensive low-protein diet: updated systematic review and meta-analysis [strong evidence]

The following meta-analysis of RCTs found no impact on kidney function followed out to two years, though the ketogenic phases of the included studies were generally much shorter than two years, limiting the strength of the conclusion:

Reviews in Endocrine and Metabolic Disorders 2020: Efficacy and safety of very low calorie ketogenic diet (VLCKD) in patients with overweight and obesity: A systematic review and meta-analysis [moderate evidence, downgraded due to short-term dietary interventions]

A similar meta-analysis looking at the effect of low-carb diets on renal function in people with type 2 diabetes found no effect. Again, study durations were variable, ranging from 5 weeks to 24 months, so it’s possible that follow-up was not long enough to see a negative effect:

Diabetes/Metabolism Research and Reviews 2018: Effect of low-carbohydrate diet on markers of renal function in patients with type 2 diabetes: A meta-analysis [strong evidence]

Another meta-analysis found a minimal improvement in eGFR with low carb:

British Journal of Nutrition 2016: Impact of low-carbohydrate diet on renal function: a meta-analysis of over 1000 individuals from nine randomised controlled trials [strong evidence]

Randomized controlled trials

There isn’t much high-quality research looking specifically at the risk of kidney stones with low-carb diets, which is why we need to rely on the pooled analysis of the first meta-analysis in the previous section. But there are some RCTs examining whether low-carb/high-protein diets can negatively impact kidney function.

This two-year trial found no adverse effects on kidney function of low carb:

Diabetes, Obesity, and Metabolism 2018: Effects of an energy-restricted low-carbohydrate, high unsaturated fat/low saturated fat diet versus a high-carbohydrate, low-fat diet in type 2 diabetes: A 2-year randomized clinical trial [moderate evidence]

This study looked at five healthy bodybuilders who continued to consume a high-protein diet (> 2.2 grams/kg/day) for a total of two years without any change in their normal kidney function measurements or other negative effects:

Journal of Exercise Physiology 2018: Case reports on well-trained bodybuilders: two years on a high protein diet [very weak evidence]

This randomized cross-over study followed 14 male bodybuilders for a year. The men ate their normal diet for a total of six months and a high protein diet for a total of six months. The study found no harmful effects on kidney function on the high protein diet:

Journal of Nutrition & Metabolism 2016: A high protein diet has no harmful effects: a one-year crossover study in resistance-trained males [randomized cross-over trial; moderate evidence]

This two-year trial randomized about 300 obese people without serious medical problems to a low-carb/high-protein weight-loss diet or a low-fat weight-loss diet. At two years, there were no significant differences between groups regarding kidney stones or overall kidney function:

Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology 2012: Comparative effects of low-carbohydrate high-protein versus low-fat diets on the kidney [moderate evidence]

Learn more

What you need to know about a low-carb diet and your kidneys

Epilepsy

Ketogenic diets have been studied extensively in children (and less extensively in adults) with epilepsy. In fact, they have been used since 1921 and are often recommended for those who either fail to respond adequately to anti-seizure medications or can’t tolerate their side effects.

Meta-analyses

The evidence in support of using ketogenic diets for children with drug-resistant epilepsy is generally strong:

Current Nutrition Reports 2022: The efficacy and safety of ketogenic diets in drug-resistant epilepsy in children and adolescents: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials [strong evidence]

This systematic review found that the evidence for effectiveness of keto in children was more certain than in adults:

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2020: Ketogenic diets for drug-resistant epilepsy [strong evidence]

Randomized controlled trials

RCTs have shown that ketogenic diets (including a less-strict version known as the modified Atkins diet, or MAD) can be very effective for seizure control in some, but not all, children and adults with epilepsy. The strength of the studies’ conclusions are often hurt by high dropout rates and significant variability of responses among individuals:

Epilepsia 2018: Effect of modified Atkins diet in adults with drug-resistant focal epilepsy: a randomized controlled trial [moderate evidence]

Acta Neurologica Scandinavica 2017: A randomized controlled trial of the ketogenic diet in refracatory childhood epilepsy [moderate evidence]

Epilepsy Research 2016: Evaluation of a simplified modified Atkins diet for use by parents with low levels of literacy in children with refractory epilepsy: a randomized controlled trial [moderate evidence]

Liver disease

Can low carb help reverse fatty liver disease? There is a growing body of evidence suggesting that low-carb and ketogenic diets do effectively reduce liver fat. At this time, much of the evidence comes from older non-randomized trials and observational studies, though the number of positive RCTs has been increasing. Meta-analyses and systematic reviews have generally come to weak conclusions, based on the small numbers of included trials and significant heterogeneity among those trials.

Meta-analyses

This systematic review included only three randomized trials comprising a total of 128 subjects. There was moderate evidence that a low-carb diet was better than a low-calorie diet for reducing liver fat, but this was based mainly on the findings from only one study of 18 people:

Metabolism 2022: The effect of dietary patterns on non-alcoholic fatty liver disease diagnosed by biopsy or magnetic resonance in adults: a systematic review of randomised controlled trials [moderate evidence, downgraded due to inclusion of only 3 small trials]

Interestingly, the next two papers (one meta-analysis and one systematic review) were both published in 2019, yet they didn’t include any clinical trials in common. The meta-analysis included both RCTs and non-randomized trials, finding little evidence that low carb is superior for reducing fat in the liver, even when accounting for the degree of carb restriction in the studies. The systematic review found the most evidence for benefit using a Mediterranean diet, though most of the included studies examined that diet vs a control diet, and none of the included studies used a true low-carb diet:

Clinical Nutrition 2019: Critical appraisal for low-carbohydrate diet in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: Review and meta-analyses [moderate evidence, downgraded due to inclusion of some non-randomized studies]

Nutrients 2019: Evaluation of dietary approaches for the treatment of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a systematic review [moderate evidence, downgraded due to heterogeneity of included studies with no true low-carb study]

This meta-analysis included non-randomized trials, finding that low carb (defined as less than 50% of calories in this review) reduced liver fat but didn’t reduce liver enzymes:

Journal of Research in Medical Sciences 2016: The effects of low carbohydrate diets on liver function tests in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials [moderate evidence, downgraded due to inclusion of non-randomized studies]

Randomized controlled trials

One RCT found that a keto diet was equivalent to a 5:2 intermittent fasting diet, and both were better than standard dietary advice for improving fatty liver:

Journal of Hepatology Reports 2021: Treatment of NAFLD with intermittent calorie restriction or low-carb high-fat diet – a randomized controlled trial[moderate evidence]

This 2-month RCT found that a very low-calorie ketogenic diet was superior to a standard low-calorie diet with respect to liver and abdominal fat loss, as well as overall weight loss:

Frontiers in Endocrinology 2020: Efficacy of a 2-month very low-calorie ketogenic diet (VLCKD) compared to a standard low-calorie diet in reducing visceral and liver fat accumulation in patients with obesity[randomized controlled trial; moderate evidence]

Another 2-month RCT showed better visceral fat loss and improvement in liver enzymes with a low-carb, high-fiber diet compared to a standard diet:

Asia Pacific Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2020: Impact of a low-carbohydrate and high-fiber diet on nonalcoholic fatty liver disease[randomized controlled trial; moderate evidence]

This RCT showed that a Mediterranean low-carb diet was more effective than a low-fat diet for reducing fat in the liver. Importantly, even after controlling for abdominal fat loss, low carb was still better at reducing liver fat than was low fat:

Journal of Hepatology: 2019 The beneficial effects of Mediterranean diet over low-fat diet may be mediated by decreasing hepatic fat content [randomized controlled trial; moderate evidence]

In an eight-week RCT of 106 people with NAFLD, those who ate a low-carb diet had greater reductions in liver fat. Although there were not statistically significant differences in body weight by the end of the trial, the low-carb group had a greater reduction in abdominal fat:

Hepatology Research 2018: Comparison of efficacy of low-carbohydrate and low-fat diet education programs in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: A randomized controlled study [moderate evidence]

Nonrandomized trials

Proceedings of the National Academy of Science U.S.A 2020: Effect of a ketogenic diet on hepatic steatosis and hepatic mitochondrial metabolism in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease [nonrandomized study; weak evidence]

This study examined the effect of a low-carbohydrate diet with increased protein and no reduction in calories on obese subjects with fatty liver disease. The research design was meant to separate the effects of caloric reduction and weight loss from those of carbohydrate restriction. The lead author noted, “We observed rapid and dramatic reductions of liver fat and other cardiometabolic risk factors and revealed hitherto unknown underlying molecular mechanisms:”

Cell Metabolism 2017: An integrated understanding of the rapid metabolic benefits of a carbohydrate-restricted diet on hepatic steatosis in humans [nonrandomized study; weak evidence]

The following study showed that liver fat was reduced to a greater extent with carbohydrate restriction that led to weight loss, as opposed to just calorie restriction that led to weight loss:

American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2011: Short-term weight loss and hepatic triglyceride reduction: evidence of a metabolic advantage with dietary carbohydrate restriction [nonrandomized study; weak evidence]

Journal of Medicinal Food 2011: The effect of the Spanish ketogenic Mediterranean Diet on nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a pilot study [nonrandomized study; weak evidence]

Learn more

Fatty liver disease and keto: 5 things to know

PCOS

Given the strong links between excess weight, high insulin levels, and other metabolic problems, a low-carb diet should be an ideal treatment for polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) — a condition usually associated with insulin resistance and obesity. Although long-term studies are lacking, the research emerging in this field is very encouraging.

Meta-analyses

This systematic review of RCTs concluded that dietary interventions improve PCOS symptoms, and low-carb is likely superior for fertility and restoring normal menstruation.

Frontiers in Endocrinology 2021: Dietary modification for reproductive health in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis [strong evidence]

This systematic review concluded that low-carbohydrate diets tend to “reduce circulating insulin levels, improve hormonal imbalance and resume ovulation to improve pregnancy rates:”

Nutrients 2017: The effect of low-carbohydrate diets on fertility hormones and outcomes in overweight and obese women: a systematic review [systematic review of randomized and nonrandomized trials; weak evidence]

The following systematic review found that low-glycemic index and low-carb diets were particularly helpful for improving some of the features of PCOS:

Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics 2013: Dietary composition in the treatment of polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review to inform evidence-based guidelines [strong evidence]

Randomized controlled trials

The following study of women with PCOS, obesity, and fatty liver randomized the participants to a ketogenic diet or conventional pharmacologic therapy. Those who received the ketogenic diet demonstrated better decreases in blood sugar and weight, and greater improvement in fatty liver:

Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Research 2021: Ketogenic diet in women with polycystic ovary syndrome and liver dysfunction who are obese: A randomized, open-label, parallel-group, controlled pilot trial [moderate evidence]

Even a very modest reduction in carbohydrates (from 55 to 41 percent of energy) can result in significant improvements in hormones and other metabolic risk factors, even in the absence of weight loss:

Clinical Endocrinology 2013: Favourable metabolic effects of a eucaloric lower‐carbohydrate diet in women with PCOS [randomized crossover trial; moderate evidence]

Nonrandomized trials

This study of 14 women with PCOS showed a significant improvement in hormone levels and markers of insulin resistance:

Journal of Translational Medicine 2020: Effects of a ketogenic diet in overweight women with polycystic ovary syndrome [nonrandomized study; weak evidence]

In a 2015 study, 24 women with PCOS who ate diets containing roughly 70 grams of net carbs per day for 12 weeks had significant reductions in insulin levels, insulin resistance, TG, and testosterone, along with an average weight loss of 19 pounds (8.6 kg) by the end of the study:

Journal of Obesity & Weight Loss Therapy 2015: Low-starch/low-dairy diet results in successful treatment of obesity and co-morbidities linked to polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) [nonrandomized study; weak evidence]

Fertility & Sterility 2006: Role of diet in the treatment of polycystic ovary syndrome [nonrandomized study; weak evidence]

One small 2005 study followed 11 women with PCOS as they went on a ketogenic low-carb diet for six months. The five women who completed the study lost weight and improved some of their hormone levels. Two of them became pregnant despite previous infertility problems:

Nutrition & Metabolism 2005: The effects of a low-carbohydrate, ketogenic diet on the polycystic ovary syndrome: a pilot study [nonrandomized study; weak evidence]

Learn more

How to potentially reverse PCOS with low carb

Irritable bowel syndrome

In recent years, much research has been done on diets low in FODMAPs. FODMAP is an acronym for “fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharide’s and polyols.” That unwieldy name describes types of short-chain carbohydrates found in many fruits, vegetables, legumes, grains, dairy products and some processed foods. Low-carb and ketogenic diets are naturally low in FODMAPs, making them an excellent choice for the treatment of IBS.

Meta-analyses

There are now numerous meta-analyses and systematic reviews of randomized and nonrandomized trials, all showing that a low-FODMAP diet is highly effective for relieving the symptoms of IBS.

Gut 2021: Efficacy of a low FODMAP diet in irritable bowel syndrome: systematic review and network meta-analysis [strong evidence]

Frontiers in Nutrition 2021: A low-FODMAP diet improves the global symptoms and bowel habits of adult IBS patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis [strong evidence]

European Journal of Nutrition 2021: Efficacy of a low-FODMAP diet in adult irritable bowel syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis [strong evidence]

This meta-analysis included both randomized and nonrandomized trials, also finding that low FODMAP is effective:

Nutrients 2021: Effect of low FODMAPs diet on irritable bowel syndromes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials [meta-analysis of randomized and nonrandomized trials; moderate evidence]

Gastroenterology Nursing 2019: Effects of low-FODMAPS diet on irritable bowel syndrome symptoms and gut microbiome [strong evidence]

One systematic review of 22 clinical trials found that a low-FODMAP approach significantly improved symptoms in people suffering from IBS:

European Journal of Nutrition 2016: Does a diet low in FODMAPs reduce symptoms associated with functional gastrointestinal disorders? A comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis [meta-analysis of randomized and nonrandomized trials; moderate evidence]

Randomized controlled trials

The following study was designed to determine whether gluten or other components of high-FODMAP foods are responsible for exacerbating IBS symptoms. The intervention group received a low-FODMAP diet + gluten powder, while the control group received a low-FODMAP diet + rice powder. The authors found that both groups experienced the same amount of improvement in symptoms, leading them to conclude that gluten is not the culprit when it comes to the exacerbation of IBS symptoms with high-FODMAP foods:

Clinical Nutrition ESPEN 2022: The effect of low FODMAP diet with and without gluten on irritable bowel syndrome: A double blind, placebo controlled randomized clinical trial [moderate evidence]

This similar study placed subjects on a low-FODMAP diet and intermittently challenged them with FODMAPs, gluten, or placebo, finding that FODMAPs caused symptoms, while gluten and placebo did not:

American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2022: Fermentable oligo-, di-, monosaccharides, and polyols (FODMAPs), but not gluten, elicit modest symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized three-way crossover trial [moderate evidence]

This novel study out of Italy was designed to see if a Tritordeum-based diet could be as effective as a low-FODMAP diet in reducing IBS symptoms among Italians (Tritordeum is a grain derived from wheat and barley, with fewer gliadins, carbs, and fructans than traditional wheat). The authors found that both groups showed equal improvements, suggesting that this might be more palatable for Italians who eat a traditional diet higher in breads and pasta:

Nutrients 2022: A comparison of the low-FODMAPs diet and a tritordeum-based diet on the gastrointestinal symptom profile of patients suffering from irritable bowel syndrome-diarrhea variant (IBS-D): a randomized controlled trial [moderate evidence]

This study showed similar improvements between the low-FODMAP and traditional dietary advice groups. But the low-FODMAP group achieved earlier improvements in stool frequency and gas. Also, severe symptoms at baseline along with the predominance of certain kinds of bacteria predicted a favorable response to the low-FODMAP diet:

American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2021: Low fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides, and polyols diet compared with traditional dietary advice for diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome: a parallel-group, randomized controlled trial with analysis of clinical and microbiological factors associated with patient outcomes [moderate evidence]

This study showed that a low-FODMAP diet was superior to traditional dietary advice, though compliance with the diet dropped from 93% at 4 weeks to 64% at 16 weeks:

Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology 2021: Low fermentable oligosaccharide, disaccharide, monosaccharide, and polyol diet in patients with diarrhea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome: A prospective, randomized trial [moderate evidence]

Learn more

Inflammatory bowel disease

There is very little research about the effects of a low-carb or ketogenic diet on inflammatory bowel diseases like Crohn’s or ulcerative colitis. However, there are some anecdotal reports suggesting that a low-carb or low-carb Paleo diet may reduce symptoms of inflammatory bowel diseases.20

Additionally, a published case report suggests that this is an area in need of further investigation:

International Journal of Case Reports and Images 2016: Crohn’s disease successfully treated with the paleolithic ketogenic diet [very weak evidence]

Randomized controlled trials

Interestingly, the only RCTs of which we are aware are decades old.

This study recruited about 200 patients after a relapse of Crohn’s disease and treated them with steroids until they were back in remission. Then, they randomized the subjects to fish oil pills, placebo, or a low-carb (84 grams/day) diet. The authors found no significant benefit of diet or fish oil over placebo, though it should be noted that overall compliance with the diet was poor, and the study suffered from other weaknesses as well:

Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology 1996: Omega-3 fatty acids and low carbohydrate diet for maintenance of remission in Crohn’s disease. A randomized controlled multicenter trial. Study Group Members (German Crohn’s Disease Study Group) [weak evidence; downgraded due to study weaknesses]

This study specifically investigated the effect of sugar and fiber, comparing groups randomized to a diet high in sugar and low in fiber vs low in sugar and high in unrefined carbohydrate. No differences were found:

British Medical Journal 1987: Controlled multicentre therapeutic trial of an unrefined carbohydrate, fibre rich diet in Crohn’s disease [moderate evidence]

Although this tiny 18-month study of 20 people (10 randomized to low-refined sugar, 10 randomized to high-refined sugar) failed to show statistically significant results, there were a couple of promising findings. In subjects with higher disease-activity scores, the “low-carb” diet seemed to improve symptoms and the high-carb diet seemed to worsen them:

Zeitschrift fur Gastroenterologie 1981: Sugar free diet: a new perspective in the treatment of Crohn disease? Randomized, control study [moderate evidence]

Reflux disease / heartburn