Low carb sweeteners, the best and the worst

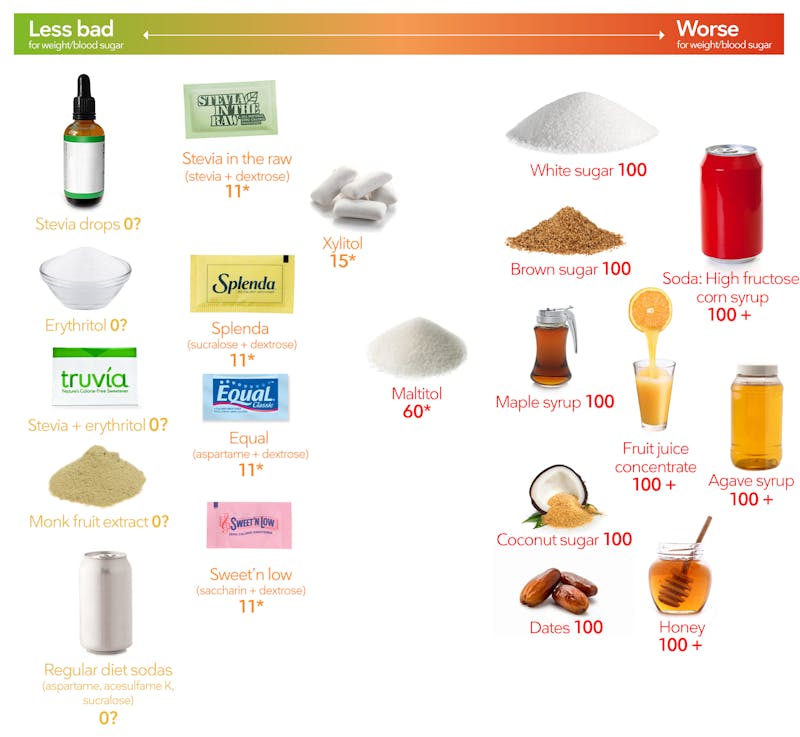

Which sweeteners can you use on a low carb diet? Check out the visual guide below. The sweeteners to the left are very low in carbs and have generally been shown to have little impact on blood sugar and insulin levels.

Numbers

The numbers above represent the effect each sweetener has on blood sugar and insulin response, in order to provide an equal amount of sweetness as white sugar (100% pure sugar). Keep in mind that many sweetener packets contain a small amount of dextrose, which is pure sugar.

For example, a packet of Splenda provides about the same sweetness as two teaspoons (8 grams) of sugar. Each packet contains about 0.9 grams of carbohydrate from dextrose. That’s 0.9 / 8 = 0.11 times the effect of sugar, for an equal amount of sweetness. Pure 100% sugar has a score of 100, so Splenda gets a number of 100 x 0.11 = 11.

If you’re aiming to stay low carb, steer clear of the sweeteners to the right in the picture above. We suggest mainly using stevia, erythritol, monk fruit, or xylitol.

Potential negative effects of all sweeteners

Note that while the sweeteners to the left above have minimal direct effects on blood sugar and insulin levels, they may still have other potential negative effects.

The question marks by the sweeteners labeled “zero” indicate that although they appear to have no effects on blood glucose and insulin, their impact on obesity, diabetes, gut health, and long-term risk for metabolic disease is not yet known. More research on the long-term impacts of these sweeteners is needed.

Additionally, the effects of artificial sweeteners on pregnant women, the developing fetus, and young children are unknown and could be risky for long-term metabolic health.

Furthermore, all sweeteners can stimulate cravings for sweet foods.

So by adding sweeteners to your foods, you may be increasing the risk that you’ll end up eating more than you need. This can slow down weight loss, or even cause weight gain. However, this doesn’t seem to happen in everyone.

If you’re able to, you may be better off just avoiding all sweeteners. Note that on a low carb diet, cravings for sugary foods tend to decrease over time, making it easier and easier to stay away from them.

However, we realize that using sugar-free sweeteners in moderation can help some people remain low carb. Like drinking a glass of wine with dinner, they may find that having a low carb brownie after dinner is completely satisfying.

If you do want to include sweeteners occasionally, keep reading to learn how to make the best low carb choices.

Using sugar as a sweetener

Note that many sweeteners – white or brown sugar, maple syrup, coconut sugar and dates – have a number of exactly 100. This is because these sweeteners are made up of sugar. Sugar is also known as sucrose, which is 50% glucose and 50% fructose.

These sweeteners will all have a similar effect on blood sugar, weight and insulin resistance.

Sugar is potentially harmful for your health — no surprise — so none of these are good options, especially if you’re on a low carb diet. Avoid.

Even worse than sugar: fructose

Some sweeteners may be even more problematic than sugar in the long run.

Regular sugar contains 50% glucose and 50% fructose.

However, certain sweeteners contain more fructose than glucose. These sweeteners are slower to raise blood glucose, resulting in a deceptively low glycemic index (GI) – a measure of how quickly a carbohydrate-containing food is digested and absorbed, and how significantly it raises blood sugar. Yet these sweeteners may still have harmful effects.

Consuming excessive fructose can increase the likelihood of developing fatty liver and insulin resistance, increasing the risk of weight gain and future health problems.

Sweeteners with higher amounts of fructose – high fructose corn syrup (soda), fruit juice concentrate, and even sweeteners marketed as “healthy” or “low glycemic index” like honey and agave syrup – might have slightly worse long-term effects compared to pure sugar.

So in addition to steering clear of sugar, it’s important to avoid these high-fructose sweeteners on a low carb diet.

Our top 4 recommendations

If consuming sweets from time to time helps you sustain your low carb journey, here are our top 4 recommendations:

Note: We recommend that people with diabetes test their blood sugar levels whenever they try a new sweetener, even if the sweetener is on our “top 4” list.

Option #1: Stevia

Pros

- Stevia doesn’t contain carbs or calories and does not raise blood sugar levels.

- It appears to be safe with a low potential for toxicity.

- Because stevia is very sweet, a little goes a long way.

Cons

- Stevia doesn’t really taste like sugar. It has a licorice-like flavor and an undeniable aftertaste when used in moderate to large mounts. Therefore, we recommend using it sparingly.

- It is challenging to cook with to get similar results as sugar and often can’t simply be swapped into existing recipes.

- There’s not enough long-term data on stevia to be certain of its true impact on the health of frequent users.

Sweetness: 200-350 times sweeter than table sugar.

Best choices: Liquid stevia or 100% pure powdered or granulated stevia. Note that some packets of granulated stevia such as Stevia in the Raw contain the sugar dextrose. The brand Truvia contains added erythritol (see below) but no dextrose.

Option #2: Erythritol

In 2023, a study showed a link between high blood levels of erythritol and an increased risk of heart attack and strokes.

Pros

- Erythritol doesn’t raise blood sugar or insulin levels.

- It provides nearly zero calories and is virtually carb-free. After being absorbed, it passes into the urine without being used by the body.

- In its granulated or powdered form it is easy to use to replace real sugar in recipes.

- Erythritol might be helpful in preventing dental plaque and cavities, compared to other sweeteners.

Cons

- Erythritol has a noticeable cooling sensation on the tongue, particularly when used in large amounts.

- Although it causes fewer digestive issues than most sugar alcohols, some people have reported bloating, gas and loose stools after consuming erythritol.

- While absorbing erythritol into the blood and excreting it into the urine appears to be safe, there may be some potential for unknown health risks (none are known at this time).

Sweetness: 70% as sweet as table sugar.

Best choices: Granulated or powdered erythritol or erythritol and stevia blends.

Option #3: Monk fruit

Monk fruit is a relatively new sugar substitute. Also called luo han guo, monk fruit was generally dried and used in herbal teas, soups and broths in Asian medicine. It was cultivated by monks in Northern Thailand and Southern China, hence its more popular name.

Although the fruit in whole form contains fructose and sucrose, monk fruit’s intense sweetness comes from non-caloric compounds called mogrosides. In 1995, Proctor & Gamble patented a method of solvent extraction of the mogrosides from monk fruit.

The US FDA has ruled that monk fruit is generally regarded as safe. It has not yet been approved for sale by the European Union.

Pros

- It is calorie-free and does not raise blood sugar or insulin levels.

- It has a better taste profile than stevia. In fact, it is often mixed with stevia to blunt stevia’s aftertaste. It is also mixed with erythritol to improve use in cooking.

- It doesn’t cause digestive upset.

- It’s very sweet, so a little goes a long way.

Cons

- It is more expensive than stevia and erythritol. However, monk fruit is often sold in cost-effective blends that contain stevia or erythritol.

- It’s often mixed with other “fillers” like inulin, prebiotic fibres and other undeclared ingredients.

- Be careful of labels that say “proprietary blend,” as the product may contain very little monk fruit extract.

- It is very new, and there aren’t any studies on its long-term effects.

Sweetness: 150-200 times sweeter than table sugar.

Best choices: Granulated blends with erythritol or stevia, pure liquid drops, or liquid drops with stevia. Also used in replacement products like monkfruit-sweetened artificial maple syrup and chocolate syrup.

Option #4: Xylitol

Unlike the other three sweeteners discussed above, xylitol is only low carb, not zero carb. So it may not be the best choice on a keto diet (below 20 grams of net carbs per day) unless used in very small amounts.

Pros

- Xylitol has a low glycemic index of 13, and only 50% is absorbed in the digestive tract.When used in small amounts, this results in a very minor impact on blood sugar and insulin levels.

- Although it tastes like sugar and has a level of sweetness identical to sugar, xylitol provides 2.5 calories per gram, whereas sugar provides 4 calories per gram.

- Like erythritol, it’s been shown to help prevent cavities, compared to most other sweeteners.

Cons

- Because 50% of xylitol is not absorbed but instead fermented by bacteria in your colon, it may cause digestive issues (such as gas, loose stools, bloating) when consumed in moderate to large amounts.

- Although xylitol is safe for humans, it is toxic and potentially lethal for pets, like cats and dogs. If you use xylitol, make sure to keep it away from your animals.

Sweetness: Equivalent in sweetness to table sugar.

Best choices: Pure granulated xylitol made from corn cob or birch wood extraction.

Although we prefer to use erythritol in most of our dessert recipes, xylitol is included in some of our ice cream recipes because it freezes better.

Other low carb sweeteners

For a more extensive list of sweeteners, see our keto sweeteners guide.

The “zero-calorie” sweeteners that are almost 100% carbs

Packets of Equal, Sweet’n Low and Splenda are labeled “zero calories,” but this isn’t the case.

FDA rules allow products with less than 1 gram of carbs and 4 calories per serving to be labeled “zero calories.” So manufacturers cleverly add about 0.9 grams of glucose/dextrose, as a bulking agent, to a small dose of artificial (synthetic) sweetener.

Voilà — a sweetener packet with a high percentage of carbs that can be labeled “zero calories” without risking a lawsuit.

The packets actually contain almost 4 calories each, and almost a gram of carbs. While 0.9 grams of carbs may not seem like much, on a very low carb or ketogenic diet it can matter — especially if you use several packets a day. Ten packets equals 9 grams of carbs.

At the very least, you should be aware of the deceptive marketing. There are also lingering potential health concerns regarding some of these synthetic sweeteners, including aspartame and sucralose.

Why maltitol is not a good option

Maltitol is the most common type of sugar alcohol used in “sugar-free” candy, desserts, and low carb products because it’s considerably less expensive than erythritol, xylitol, and other sugar alcohols.

Maltitol is not a good choice for people on low carb diets. About 50% of this sweetener is absorbed in the small intestine, which can raise blood sugar and insulin levels, especially in those with diabetes or prediabetes.

In addition, the roughly 50% that’s not absorbed is fermented in the colon. Studies have shown that maltitol may cause significant digestive distress (gas, bloating, diarrhea, etc.), especially when consumed in large amounts.

Diet soft drinks – yes or no?

There’s some research suggesting that diet beverages may make it harder to lose weight, despite containing no calories.

What’s more, a 2016 study found that most studies showing a favorable or neutral relationship between sugar-sweetened beverages and weight were funded by industry and full of conflict of interest, research bias and unreproduced findings.

However, if you feel you must drink diet sodas, at least they will allow you to stay low carb. Regular soda, sweetened with sugar or HFCS, will very quickly result in a high carb intake, negating the positive effects of a low carb diet.

A final word on low carb sweeteners

While some sweeteners may be better than others, the best strategy for achieving optimal health and weight loss may be learning to enjoy real foods in their unsweetened state. Over time, you may discover a whole new appreciation for the subtle sweetness of natural, unprocessed foods.

However, some people may not lose their taste for sweets. If you are one of them, occasionally using sweeteners may make it easier for you to stick with low carb.

Determining whether including low carb sweeteners makes sense for you is key to achieving long-term success.

Sugar addiction

Can’t imagine living without sweet foods? If you try, do you find it almost impossible to curb the cravings? Do you find yourself then binging on sweets? You might be interested in our course on sugar addiction and how to take back control. And yes, you can do it!