What is prediabetes & how can you reverse it?

Evidence based

Have you been told that you have prediabetes or that you’re at risk for type 2 diabetes? You’re not alone. Prediabetes is extremely common, affecting more than one third of all American adults. The good news is that you can control, or even reverse, this condition by making a few simple diet and lifestyle changes — no medications required.

Read on to learn about prediabetes and the steps you can take today to reverse it.

What is prediabetes?

Prediabetes is a health condition in which your blood sugar levels are above the normal range but not high enough for you to be diagnosed with diabetes.

It is one of the most common conditions in the modern world, and the number of people affected by this condition is growing steadily.

According to one study, about 88 million adults living in the US had prediabetes in 2020. Today, the CDC estimates that roughly 96 million American adults have prediabetes — about 38% of the US population, or more than 1 in 3 people. And most people with prediabetes are unaware that they have it.

By contrast, the CDC estimates that about 37 million American adults, or 1 in 7 people, have diabetes.

Where does the high blood sugar come from?

The sugar (glucose) in your blood comes from eating certain foods and from your liver. Your liver stores sugar and releases it into your bloodstream as needed.

When you eat sugar and starches, they are broken down into glucose and quickly absorbed into your blood. This causes your blood sugar to begin rising. In response, your pancreas produces insulin, a hormone that directs glucose to move from your blood into your cells. When this is working well, the sugar, or glucose, in your blood stays within a narrow range.

If you have prediabetes, in most cases, your pancreas produces insulin normally, but your cells don’t fully respond to insulin’s effects. This is called insulin resistance, and it causes blood sugar to increase above the healthy range. As a result, your pancreas produces even more insulin in an attempt to return high blood sugar to normal levels.

During prediabetes, your blood sugar and insulin levels may gradually increase over several years. In short, you don’t go from having normal blood sugar one day to having type 2 diabetes the next. It’s an evolving process. And prediabetes is the intermediate step.

In some cases, diabetes complications can start developing during the prediabetes stage — including eye, kidney, and nerve damage — years before any symptoms occur. Having prediabetes also increases your risk of heart disease.

So, it’s important to take prediabetes seriously.

How do I know if I have prediabetes?

What are the signs of prediabetes? You probably won’t have any. This may be why most people aren’t aware that they have prediabetes: they don’t have any concerning symptoms that prompt them to visit their doctor.

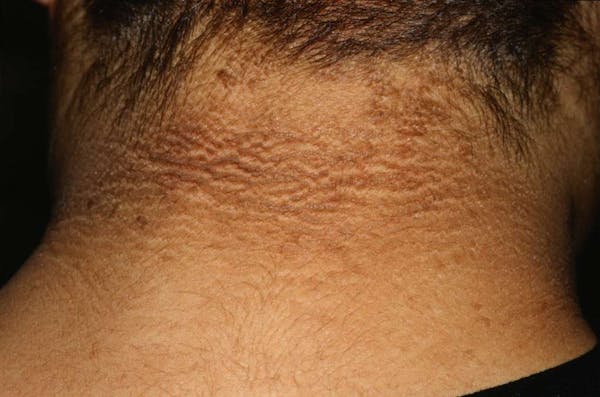

One possible subtle prediabetes symptom is darkened skin in the folds of your neck, armpits, or groin. The medical term for these patches is acanthosis nigricans. You may develop these darkened areas of skin if you have elevated insulin levels and insulin resistance.

Your doctor can diagnose you with prediabetes if you meet one or more of three criteria

- a fasting blood glucose level between 100 to 125 mg/dL (5.6 to 7.0 mmol/L)

- a hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) of 5.7% to 6.4% (39 to 46 mmol/mol)

- a blood glucose level between 140 and 199 mg/dL (7.8 to 11 mmol/L) two hours after drinking a solution with 75 grams of glucose during an oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT)

Because they are routine blood tests, fasting blood glucose and HbA1c are the most common methods for diagnosing prediabetes. Check your most recent lab report for these values. If you don’t see an HbA1c on your lab report, you may want to ask your doctor to order one.

You can also buy a blood glucose meter at any pharmacy to check your blood sugar levels at home. However, keep in mind that these meters provide less accurate results than laboratory blood tests. While a meter can help you monitor your blood sugar, you’ll need a lab test for a formal prediabetes diagnosis.

How to reverse prediabetes

1. Diet

You can take steps to reverse prediabetes in ways that fit your preferences and abilities. Let’s start with the most important one: changing the way you eat. If you are overweight with too much body fat, any healthy weight loss could lower the risk of prediabetes. However, two eating patterns likely help more than others: low carb and high protein.

Cut back on carbs

Bread, potatoes, fruit, and other foods contain carbohydrates (carbs), which your body breaks down into glucose (sugar). The glucose is absorbed into your blood, which raises your blood sugar. So it shouldn’t be surprising to hear that eating fewer carbs can be beneficial for lowering blood sugar.

Indeed, strong evidence shows that people with type 2 diabetes who follow a low carb diet can safely and effectively improve their blood sugar control and lose weight. Although we have much less research on carb reduction in people with prediabetes, the results so far are encouraging.

In a 2021 trial, 96 people with prediabetes followed a very low carb diet for two years. At the end of the trial, more than 50% of the participants had lowered their blood sugar to normal levels. Additionally, they lost an average of 26 pounds (12 kilos) and reduced their fasting insulin levels.

Although this wasn’t a randomized trial with a control group, it shows that people with prediabetes can completely reverse their condition by eating very few carbs. Also important: an impressive 75% of participants completed the two-year trial, demonstrating that this way of eating is sustainable long term.

In a 12-month randomized trial, people with prediabetes who ate a very low carb diet lowered their blood sugar and lost more weight than those who ate a moderate carb diet. Another 12-month randomized trial found that significantly more people who ate a low carb diet achieved normal blood sugar levels compared to those who followed a higher carb diet.

Importantly, not everyone with prediabetes is overweight. Following a very low carb diet can improve your blood sugar levels even if you don’t need to lose weight.

How to eat a healthy low carb prediabetes diet

How low carb do you need to go to reverse prediabetes? In the studies above, people consumed between 30 grams to 50 grams of total carbs (about 20 to 30 grams of net carbs) per day. However, you may be able to keep your blood sugar within a healthy range by eating slightly more carbs.

You can determine your personal carb tolerance by testing your blood sugar 1 to 2 hours after eating to make sure you stay below 140 mg/dL (7.8 mmol/L).

A prediabetes diet can include these low carb foods:

- protein: meat, poultry, seafood, eggs, Greek yogurt, cheese, tofu, and edamame

- non-starchy vegetables: greens, asparagus, cauliflower, broccoli, avocados, cucumbers, and many more

- smaller amounts of berries, nuts, seeds, butter, and oil

Low carb meal planning for prediabetes

How can you put together a nutritious, satisfying meal that will keep your blood sugar within the normal, healthy range? Just follow these four easy steps:

- Start with a generous serving of protein. Aim for at least 4 ounces (113 grams) — a piece of meat, seafood, or tofu slightly larger than the size of a deck of cards.

- Include as many non-starchy vegetables as you want.

- Use about a tablespoon or two of fat (such as butter or olive oil) for cooking, in salad dressing, or to add to your food at the table.

- Season with salt and spices. Adding salt can be especially helpful for relieving symptoms of the keto flu that often occur when starting a very low carb diet.

Or try our tasty low carb, high protein recipes, such as

Eat a high protein diet

Getting plenty of protein is important. Why? For starters, protein provides essential amino acids that your body requires to build and maintain muscle. In addition, eating a high protein diet can help you feel full and satisfied, slightly boost your metabolism, and improve your body composition.

Plus, consuming more protein may help reverse prediabetes.

In a small trial, 100% of people with prediabetes who ate a high protein, moderate carb diet for six months achieved normal blood sugar levels. Importantly, the studies discussed earlier that reported prediabetes reversal with a very low carb diet were also higher in protein than the comparison diet.

2. Additional dietary strategies to reverse prediabetes

Weight loss

While a keto or low carb diet is likely the most effective way to reverse prediabetes, people who are carrying excess weight can improve their prediabetes by losing weight with either low carb or other dietary approaches that provide adequate protein.

Plus, if you lose weight in a healthy way — by losing body fat while maintaining your muscle — you’ll be even more likely to achieve healthy blood sugar levels and prevent type 2 diabetes. You can learn more about healthy weight loss in our complete guide.

Avoid high carb foods

To reverse prediabetes, avoid pasta, rice, bread, potatoes, and most high-sugar fruit other than berries. These foods can raise blood sugar due to their high carb content.

Stay far away from ultra-processed foods that are high in both carbs and fat, such as candy bars, doughnuts, chips, and similar products. In addition to raising blood sugar, eating these products can promote weight gain. Some researchers suggest that these foods may even be addictive.

Finally, don’t drink your calories. Sugary beverages like soda, sweetened coffee and tea, and fruit juice can rapidly raise blood sugar. And even low carb alcoholic drinks can increase your appetite and decrease your inhibitions, which may lead you to overeat without even realizing it. So go easy with alcohol and avoid sweetened beverages altogether.

3. Exercise

Although changing your diet is the most important step for reversing prediabetes, several types of physical activity can also be helpful:

Aerobic or cardiovascular (cardio) exercise

As you may have heard, doing an activity that raises your heart rate — such as running, cycling, or dancing — can help you lose body fat. In studies, engaging in aerobic exercise several times a week has also been shown to improve blood sugar response in people with prediabetes, even when performed at moderate intensity, such as brisk walking.

High-intensity interval training

Rapid bursts of strenuous exercise alternating with periods of lower-intensity movement is known as high-intensity interval training (HIIT). Research suggests it may help you burn more calories than other forms of exercise performed for the same duration.

And studies demonstrate that it can help lower blood sugar, improve insulin resistance, and burn body fat in those with prediabetes or obesity.

Resistance training

Strength training (lifting weights or pushing or lifting your own body weight, such as doing push-ups or chin-ups) can help you build muscle and burn more calories at rest. Researchers report that, like other forms of exercise, resistance training can help people with prediabetes improve their blood sugar levels and reduce their risk of developing type 2 diabetes.

Some theorize that building muscle via resistance training may play a role in reducing blood sugar because the incremental muscle mass acts as a “sink” that takes up glucose more easily.

So, which type of exercise should you do? Since many different kinds of exercise can help improve prediabetes, it’s best to choose activities you enjoy and can do several times a week consistently.

But remember, changing how you eat is essential for conquering prediabetes. Eating a diet high in fast-digesting carbs has been shown to interfere with the blood sugar benefits of exercise.

Learn more about different types of exercise and how to get started in our complete exercise guide.

4. Other lifestyle changes

Besides changing the way you eat and exercise, you can take additional steps to improve prediabetes, such as:

Getting enough sleep

Do you get plenty of high-quality sleep on a regular basis? Lack of sleep has been shown to increase blood sugar levels and insulin resistance. Research suggests that people with prediabetes who don’t get enough sleep may be more likely to progress to type 2 diabetes.

How many hours of sleep do you need? Many experts suggest we need at least seven hours of sleep, but this seems to vary from person to person and may change with age and other factors. What’s important is getting the amount of restorative sleep that’s right for you, so you can feel and perform your best.

To improve your sleep, get up and go to bed around the same times every day, don’t drink caffeinated beverages after lunch, and avoid cell phones and other screens before bedtime.

Managing stress

While having some stress is a normal part of life, feeling overly stressed for extended periods of time can play havoc with your health. For one thing, chronic stress may worsen insulin resistance.

Although you may not be able to get rid of stress, you can reduce or manage it. Engaging in meditation and mindful practices may help. Other activities that help you relax — such as walking, dancing, or talking with a friend — may also be beneficial.

What are the risk factors for prediabetes?

According to the CDC, several factors can increase your risk of prediabetes, including:

- having a BMI of 25 or more, especially if you carry excess weight around the middle and have other features of metabolic syndrome, such as elevated blood pressure

- being 45 years or older

- having a family history of type 2 diabetes, especially if you do not have obesity

- living a sedentary lifestyle

- having a history of gestational diabetes

- being of African, Indian, Hispanic, Pacific Islander, or Native American ethnicity

Women with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) are also at increased risk of prediabetes.

Although meeting one or more of these criteria doesn’t mean that you will definitely get prediabetes, it increases your risk of developing it. So if you fall into any of these categories, you may want to get tested for prediabetes and start making lifestyle changes now to prevent developing prediabetes in the future.

Does having prediabetes mean I will get type 2 diabetes?

Based on the most recent research, more than half of all people with prediabetes are expected to develop diabetes at some point in their lifetime, while others will never progress beyond prediabetes.

In some studies, people with a fasting blood sugar level or A1c at the upper end of the prediabetes range were more likely to eventually develop type 2 diabetes than those whose levels were closer to the normal range.

But no matter where your blood sugar levels are now, you can control or even reverse prediabetes by changing how you eat and adopting other healthy lifestyle habits.

You have the power to achieve normal, healthy blood sugar and prevent type 2 diabetes — by taking control of your health. Start today!

What is prediabetes and how can you reverse it? – the evidence

This guide is written by Franziska Spritzler, RD and was last updated on June 28, 2022. It was medically reviewed by Dr. Bret Scher, MD on May 17, 2022.

The guide contains scientific references. You can find these in the notes throughout the text, and click the links to read the peer-reviewed scientific papers. When appropriate we include a grading of the strength of the evidence, with a link to our policy on this. Our evidence-based guides are updated at least once per year to reflect and reference the latest science on the topic.

All our evidence-based health guides are written or reviewed by medical doctors who are experts on the topic. To stay unbiased we show no ads, sell no physical products, and take no money from the industry. We’re fully funded by the people, via an optional membership. Most information at Diet Doctor is free forever.

Read more about our policies and work with evidence-based guides, nutritional controversies, our editorial team, and our medical review board.

Should you find any inaccuracy in this guide, please email andreas@dietdoctor.com.

Current Medical Research and Opinion 2019: Understanding prediabetes: definition, prevalence, burden and treatment options for an emerging disease [overview article; ungraded]

Journal of the American Medical Association 2021: Screening for prediabetes and type 2 diabetes: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement [overview article; ungraded]

Although most people with prediabetes have insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia, those who are not overweight or obese may have elevated blood sugar levels that are mainly due to defects in insulin secretion or insulin signaling:

Cureus 2020: The pathophysiology of type 2 diabetes mellitus in non-obese individuals: an overview of the current understanding [overview article; ungraded]

Applied Physiology, Nutrition, and Metabolism 2007: Non-obese patients with type 2 diabetes and prediabetic subjects: distinct phenotypes requiring special diabetes treatment and (or) prevention? [overview article; ungraded]

Medicine 2020: The roles of first phase, second phase insulin secretion, insulin resistance, and glucose effectiveness of having prediabetes in nonobese old Chinese women [observational study; weak evidence]

This doesn’t happen in every case, however. According to a 2019 review, about 25% of people with prediabetes will develop type 2 diabetes within 3 to 5 years, and up to 70% of people with prediabetes may develop type 2 diabetes within their lifetime:

Clinical Diabetes and Endocrinology 2019: Global epidemiology of prediabetes – present and future perspectives [overview article; ungraded]After analyzing data from large national health surveys, researchers found that among people with prediabetes, approximately 8% had retinopathy (eye damage), 7% to 15% had neuropathy (nerve damage), and 18% had chronic kidney disease:

Clinical Diabetes and Endocrinology 2019: Global epidemiology of prediabetes – present and future perspectives [overview article; ungraded]

According to early research, people with certain forms of prediabetes are at high risk of developing these complications even if they never progress to type 2 diabetes:Nature Medicine 2021: Pathophysiology-based subphenotyping of individuals at elevated risk for type 2 diabetes [observational study; very weak evidence]

Diabetes Care 2021: Prediabetes defined by first measured HbA1c predicts higher cardiovascular risk compared with HbA1c in the diabetes range: a cohort study of nationwide registries [observational study; weak evidence]

Atherosclerosis 2018: Prediabetes and cardiovascular disease risk: A nested case-control study [case-control study; weak evidence]

International Journal of Clinical Practice 2020: Acanthosis nigricans in middle-age adults: A highly prevalent and specific clinical sign of insulin resistance [observational study; very weak evidence]

Journal of Cosmetic Dermatology 2020: Acanthosis nigricans: A review [overview article; ungraded]

A 2017 study that tested 17 different brands of glucose meters found that their results were off by anywhere from 5.6% to 20.8% compared to blood tested in a lab:

Journal of Diabetes Science and Technology 2017: Comparative accuracy of 17 point-of-care glucose meters [comparative study; weak evidence]

Nutrients 2020: Impact of a ketogenic diet on metabolic parameters in patients with obesity or overweight and with or without type 2 diabetes: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials [strong evidence]

Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice 2018: Effect of dietary carbohydrate restriction on glycemic control in adults with diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis [strong evidence]

Diabetes, Obesity & Metabolism 2019: An evidence‐based approach to developing low‐carbohydrate diets for type 2 diabetes management: a systematic review of interventions and methods [strong evidence]

Nutrients 2021: Type 2 diabetes prevention focused on normalization of glycemia: a two-year pilot study [non-randomized study; weak evidence]

Nutrition and Diabetes 2017: Twelve-month outcomes of a randomized trial of a moderate-carbohydrate versus very low carbohydrate diet in overweight adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus or prediabetes [randomized study; moderate evidence]

Nutrients 2020: Prediabetes conversion to normoglycemia is superior adding a low carbohydrate and energy deficit formula diet to lifestyle intervention: a 12-month subanalysis of the ACOORH trial [randomized trial; moderate evidence]

A 2016 analysis of NHANES data found that 18.5% of normal-weight adults aged 20 years or older had prediabetes and that less than half of these individuals had a waist circumference classified as unhealthy:

Annals of Family Medicine 2016: Prevalence of prediabetes and abdominal obesity among healthy-weight adults: 18-year trend [observational study; weak evidence]

JCI Insight 2019: Dietary carbohydrate restriction improves metabolic syndrome independent of weight loss [randomized trial; moderate evidence]

Net carbs = total carbs minus dietary fiber.

Journal of the American College of Nutrition 2004: The effects of high protein diets on thermogenesis, satiety and weight loss: a critical review [systematic review of randomized trials; strong evidence]

Nutrition Reviews 2016: Effects of dietary protein intake on body composition changes after weight loss in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis [systematic review of randomized trials; strong evidence]

Nutrition, Metabolism and Cardiovascular Diseases 2021: High protein diet leads to prediabetes remission and positive changes in incretins and cardiovascular risk factors [randomized trial; moderate evidence]

In a 2020 randomized trial of 180 people, those who followed a moderate carb, lower fat diet had greater weight loss and prediabetes reversal than those in the control group:

Nutrients 2020: Reversal of prediabetes in Saudi Adults: results from an 18 month lifestyle intervention [randomized trial; moderate evidence]

In a three-year randomized trial of more than 2,000 people with prediabetes, far fewer participants progressed to type 2 diabetes than predicted, whether they followed a higher protein, lower carb diet or a moderate protein, moderate carb diet combined with increased physical activity:

Diabetes, Obesity and Metabolism 2021: The PREVIEW intervention study: Results from a 3-year randomized 2 x 2 factorial multinational trial investigating the role of protein, glycaemic index and physical activity for prevention of type 2 diabetes [randomized trial; moderate evidence]

Studies demonstrate that starchy foods like rice and bread can raise blood sugar levels as much as sweet foods:

Journal of Insulin Resistance 2016: It is the glycemic response to, not the carbohydrate content of food that matters in diabetes and obesity: the glycemic index revisited [case series; weak evidence]

In a study conducted in an inpatient hospital ward, 20 people ate a non-calorie-restricted ultra-processed diet and non-calorie-restricted minimally processed diet for two weeks each, in random order. The participants ate an average of 500 calories more per day on the ultra-processed diet — entirely from carbohydrates and fats — and gained 2 pounds (0.9 kilos), on average:

Cell Metabolism 2019: Ultra-processed diets cause excess calorie intake and weight gain: An inpatient randomized controlled trial of ad libitum food intake [randomized trial; moderate evidence]

PLoS One 2015: Which foods may be addictive? The roles of processing, fat content, and glycemic load [non-randomized trial; weak evidence]

British Journal of Nutrition 2019: The effect of alcohol consumption on food energy intake: a systematic review and meta-analysis [strong evidence]

Journal of Applied Physiology 2012: Effects of aerobic and/or resistance training on body mass and fat mass in overweight or obese adults [randomized trial; moderate evidence]

Diabetologia 2016: Effects of exercise training alone vs a combined exercise and nutritional lifestyle intervention on glucose homeostasis in prediabetic individuals: a randomised controlled trial [randomized trial; moderate evidence]

Obesity Reviews 2015: The effects of high-intensity interval training on glucose regulation and insulin resistance: a meta-analysis [strong evidence]

Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 2017: Aerobic exercise training modalities and prediabetes risk reduction [randomized trial; moderate evidence]

British Journal of Sports Medicine 2017: Effects of high-intensity interval training on cardiometabolic health: a systematic review and meta-analysis of intervention studies [systematic review of randomized trials; strong evidence]

Journal of Sports Science and Medicine 2019: Two weeks of interval training enhances fat oxidation during exercise in obese adults with prediabetes [systematic review of randomized trial; moderate evidence]

Sports Medicine 2021: The effect of resistance training in healthy adults on body fat percentage, fat mass and visceral fat: a systematic review and meta-analysis [strong evidence]

Journal of Diabetes 2020: Comparing the effects of 6 months aerobic exercise and resistance training on metabolic control and β-cell function in Chinese patients with prediabetes: A multicenter randomized controlled trial [strong evidence]

Diabetes Metabolism Research and Reviews 2019: Two-year-supervised resistance training prevented diabetes incidence in people with prediabetes: a randomised control trial [moderate evidence]

However, this is a mechanistic theory that hasn’t been proven:

Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine 2018: The essential role of exercise in the management of type 2 diabetes [overview article; ungraded]

Acta Diabetologica Latina 2019: Exercise-induced improvements in glucose effectiveness are blunted by a high glycemic diet in adults with prediabetes [randomized trial; moderate evidence]

Lancet 1999: Impact of sleep debt on metabolic and endocrine function [non-randomized study; weak evidence]

Healthcare (Basel) 2019: The interlinked rising epidemic of insufficient sleep and diabetes mellitus [overview article; ungraded]

Diabetic Medicine: A Journal of the British Diabetic Association 2017: Sleep duration and progression to diabetes in people with prediabetes defined by HbA 1c concentration [observational study; very weak evidence]

Nature and Science of Sleep 2018: Sleeping hours: what is the ideal number and how does age impact this? [overview article; ungraded]

Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology 2018: More than a feeling: A unified view of stress measurement for population science [review article; ungraded]

Psychoneuroendocrinology 2005: Role of stress in the pathogenesis of the metabolic syndrome [overview article; ungraded]

Journal of Epidemiology 2016: Investigation of the relationship between chronic stress and insulin resistance in a Chinese population [cross-sectional observational study; very weak evidence]

International Journal of Yoga 2018: Effect of 6 months of meditation on blood sugar, glycosylated hemoglobin, and insulin levels in patients of coronary artery disease [randomized trial; moderate evidence]

Archives of Internal Medicine 2006: Effects of a randomized controlled trial of transcendental meditation on components of the metabolic syndrome in subjects with coronary heart disease [moderate evidence]

We recognize that body weight and BMI are crude measurements that may not reflect the metabolic health of an individual. However, from a population standpoint, they tend to track fairly well with metabolic risk.

Journal of the American Medical Association 2021: Screening for prediabetes and type 2 diabetes: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement [overview article; ungraded]

PLoS One 2015: Prevalence and predictors of pre-diabetes and diabetes among adults 18 years or older in Florida: a multinomial logistic modeling approach [observational study; weak evidence]

Metabolic Syndrome and Related Disorders 2019: Prevalence of metabolic syndrome in prediabetes [observational study; weak evidence]

Acta Diabetologica 2019: Prediabetes defined by HbA 1c and by fasting glucose: differences in risk factors and prevalence [observational study; very weak evidence]

Journal of Diabetes Research 2019: A case-control study on risk factors and their interactions with prediabetes among the elderly in rural communities of Yiyang City, Hunan Province [case-control study; weak evidence]

Diabetologia 2013: Family history of diabetes is associated with higher risk for prediabetes: a multicentre analysis from the German Center for Diabetes Research [observational study; weak evidence]

BMJ Open Diabetes Research and Care 2016: Physical activity, sedentary behaviors and the incidence of type 2 diabetes mellitus: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) [observational study; weak evidence]

BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth 2022: Glucose levels during gestational diabetes pregnancy and the risk of developing postpartum diabetes or prediabetes [observational study; weak evidence]

European Journal of Endocrinology 2018: Gestational diabetes with diabetes and prediabetes risks: A large observational study [observational study; weak evidence]

Non-white individuals without obesity are more likely to have prediabetes or elevated blood sugar levels compared to white individuals without obesity:

Diabetes Care 2019: Racial/ethnic disparities in the prevalence of diabetes and prediabetes by BMI: Patient Outcomes Research to Advance Learning (PORTAL) multisite cohort of adults in the U.S [observational study; weak evidence]

Diabetes Care 2013: Race/ethnicity disparities in dysglycemia among U.S. women of childbearing age found mainly in the nonoverweight/nonobese [observational study; weak evidence]

Risk of prediabetes appears to be especially high in women with PCOS who also have a BMI in the overweight or obese range:

Human Reproduction 2017: Overweight and obese but not normal weight women with PCOS are at increased risk of Type 2 diabetes mellitus-a prospective, population-based cohort study [observational study; weak evidence]

Bosnian Journal of Basic Medical Sciences 2016: Incidence of prediabetes and risk of developing cardiovascular disease in women with polycystic ovary syndrome [observational study; weak evidence]

BMJ Open Diabetes Research and Care 2020: Lifetime risk to progress from pre-diabetes to type 2 diabetes among women and men: comparison between American Diabetes Association and World Health Organization diagnostic criteria [observational study; weak evidence]

Population health management 2017: Incidence rate of prediabetes progression to diabetes: modeling an optimum target group for intervention [observational study; weak evidence]

Nutrients 2020: Lifestyle and progression to type 2 diabetes in a cohort of workers with prediabetes [observational study; weak evidence]