Dr. Palavecino brings low-carb to rural Delaware

Photo by James Hill

In Dr. Sandra Palavecino’s small community of Seaford, Delaware, everyone calls her “Dr. P.”

She’s a specialist in obesity and internal medicine in the rural community, where obesity is a significant issue. One in three adults is obese in Delaware; the rate is increasing every year.

At Dr. P’s Nanticoke Weight Loss program, she’s known for telling patients to ditch low-fat foods and to instead embrace fats like butter and bacon while cutting out sugar and refined carbohydrates.

The community is noticing the results.

Many of her patients have lost dozens, even hundreds of pounds, and they’ve improved health issues like high blood pressure, diabetes, joint pain, and more.

So when Dr. Palavecino shops at one of the town’s two grocery stores, other shoppers peer into her cart to see what low-carb food the obesity doctor is buying for her family. (Her husband’s the town’s endocrinologist, plus, she has two teenage children.)Some hold up items, asking: “Hey, Dr. P, should I buy this yogurt? Or this one with more fat?”

“Often they’re not even my patients,” laughs Dr. Palavecino.

Happy now, frustrated before

Dr. Palavecino doesn’t mind the questions or the scrutiny. She loves what she does. She wants to improve the health of as many people as possible. She relishes when people find success, even if it’s just from hearing about the low-carb diet from others.

In videos of Dr. P talking with patients, such as the local pastor who lost 100 pounds, you can clearly see the warmth, respect, and admiration she has for her clients’ success.

There’s nothing she likes better than to see patients come off medications, lose 30 or 40 pounds (14 or 18 kilos), or reverse their diabetes or high blood pressure.

“It’s the best!,” Dr. Palavecino says.

She didn’t always feel this happy and effective. Between 2012 and 2015, when she was working as a primary care physician in the same community, she felt frustrated, bewildered, and ineffective.

“There was so much obesity, diabetes, and chronic disease. I was trying to do my best as a doctor, but patients would come back for the next appointment and they would be worse.

“No one was getting better. I didn’t feel like I was helping at all. I was asking myself constantly, ‘Why is nothing happening? What is going on?’”Then, in 2015, to seek out better answers, Dr. P attended a medical conference on obesity. By sheer chance, she heard a speech by Dr. Andreas Eenfeldt, the founder of Diet Doctor.

“I will never forget that talk by Dr. Eenfeldt. It was jaw-dropping to me! Everyone talks about their ‘aha’ moment. That was mine.”

From that moment on, her life — and her patients’ lives — began to change.

From the Amazon jungle to the chicken farms of Delaware

How Dr. Palavecino ended up in a small community in rural Delaware is its own story.

Born in Chile, and raised in Venezuela, Dr. Palavecino wasn’t one of those kids who always dreamed of medicine. “People just said, ‘you have good grades, you should be a doctor.’ So I said, ‘okay!’”

Only 16 when she graduated from Venezuela’s secondary school system, Dr. Palavecino deferred her acceptance into medical school for a year because her parents felt she was too young to move to Caracas for training. Instead, she took a year to learn English, living with a family in Wisconsin. It was her first experience of English, America, and small-town rural life.

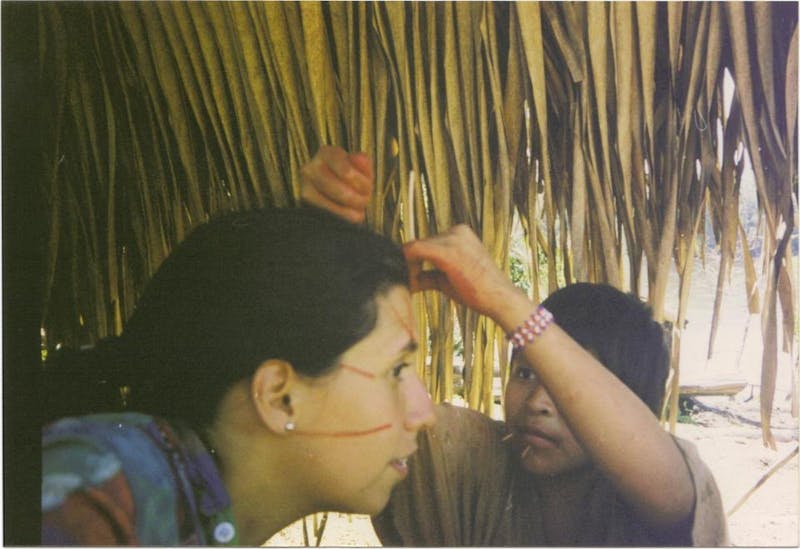

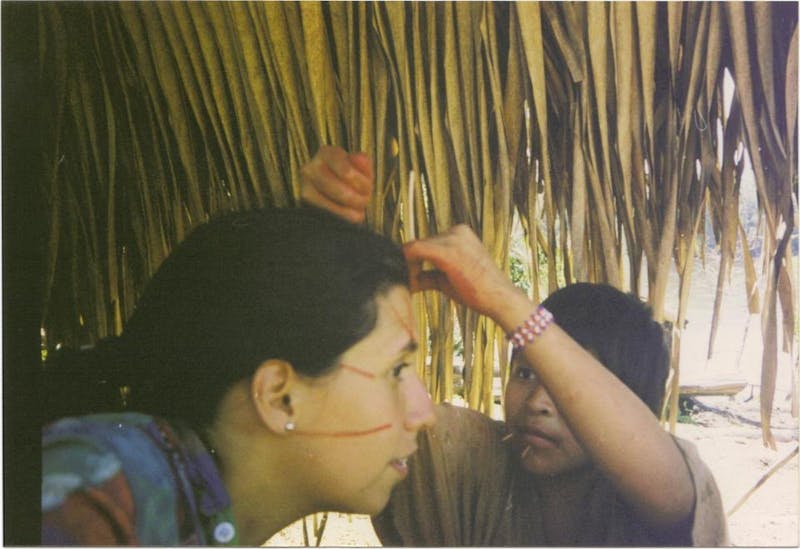

Once she started med school, Dr. Palavecino loved every minute of it. Since medical school is free in Venezuela, upon graduation she was required to pay back her education by working in an underserved area. She wound up as a physician in the Amazon jungle, looking after the health needs of the remote Yanomami tribes.

“I looked after everything — skin issues, infections. But the major health issue was malaria. My daily work was to go around by boat to find communities to test and treat for malaria. It was the most amazing time that I could ever describe.”

The experience cemented a love of infectious disease and tropical medicine. After practicing in the jungle, she worked in the biggest hospital in the country, looking after the most complex patients with AIDS, hepatitis C, and tropical diseases.

However, with social and economic upheaval beginning in Venezuela, she and her physician husband decided to move to the US with their 2-year-old daughter in 2006. They settled first in Connecticut.

US exams and training young doctors

Foreign-trained doctors face a stringent set of exams and requirements to become licensed in the US.

Dr. Palavecino studied for two years to pass the US exams, during that time giving birth to her son. She then got a job at the University of Connecticut Medical School, teaching medical students how to do effective medical interviews.

“Part of my job was being a patient actor. I would pretend to have an illness, like undiagnosed diabetes. I would come in with a complaint like blurry vision or excessive thirst and the med students would then have to ask me questions and examine me.”She would then give feedback to the students to help them improve their patient interactions. “I would say things like ‘Your questions need to be more open or you were not empathetic to me; you made me feel bad.'”

No doubt this role as a pretend patient helped hone her own skills. “It was super cool,” Dr. Palavecino says.

She was trying to get a position as an infectious disease doctor in Connecticut when her husband landed the position in 2012 as an endocrinologist in Seaford. She was offered a job there, too, but as a primary care physician in a small clinic. It wasn’t her dream job, but she told her husband: “Let’s go. You need to do this and I will be fine.”

That was how she found herself practicing primary medicine in a small rural town, looking after patients with obesity and diabetes that she felt increasingly frustrated she could not help.

“I worried that my passion for infectious disease meant that I didn’t have the necessary medical or nutritional knowledge. I told myself ‘there has to be something more I can do for these people.’”Struggling with her own weight

Dr. P had her own health-related frustrations, too. Since arriving in the US, she’d gained about 20 pounds (9 kilos) that she couldn’t lose from her second pregnancy and her life as a busy doctor.

Her triglycerides were rising, too. “I was developing metabolic syndrome for sure. And nothing I did seemed to make a difference.”

She decided she needed more training. She signed up for a two-day obesity medicine conference in 2015 in Philadelphia.

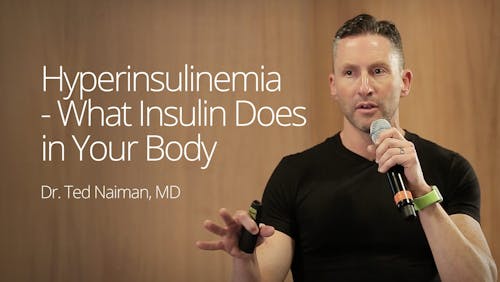

That was where Dr. P first heard Dr. Andreas Eenfeldt giving his food revolution talk. He is a hero to her, and while she was too shy in 2015 to ask for a picture, she’s proud of a grainy dark photo (above) she had taken with him at the 2018 Low Carb Denver conference. “He changed my life.”

She remembers listening to his presentation. “I was so excited. I was thinking, ‘This is not only what I want to do for myself, [but] this is what I want to do for my living.’”

That night, while staying in the hotel, she picked up veggies, meat, cheese from a local market and began eating a low-carb, high-fat diet right away. “I told myself, ‘This is the way I am going to eat for the rest of my life.’”Clicked from the start

The diet worked like no diet had before. “I’d been the typical low-fat, low-calorie dieter, eating Special K, 100-calorie items. And none of it worked. But this clicked from the start.”

But she was nervous to go against mainstream medical advice and tell patients to eat fewer carbs and more fat.

“The first time I told a patient ‘I want you to switch out your oatmeal for bacon and eggs for breakfast’, I almost had to whisper it. I could hardly say it out loud, even though I had already begun eating that way and was already feeling and seeing the difference.”Dr. Palavecino practiced the way she explained low-carb eating, trying to work the information effectively into a standard patient visit.

It wasn’t easy. She realized she needed to specialize as an obesity physician so she didn’t have to shoe-horn a discussion about diet into a 15-minute primary care appointment.

“I told myself, good or bad, I have to do the obesity boards [exam]. I don’t know what I will do with it, but I just have to do it.”

Specialized obesity clinic

Just as she was undergoing her obesity specialization, the town’s hospital hired a bariatric surgeon and set up an obesity clinic. Dr. Palavecino applied to work there and was hired part-time.

Before long, she was working full time to oversee patients for medical weight loss as well as doing all the pre-op and post-op medical visits and counseling for surgery patients.

While the majority of her practice is helping obese patients by using a low-carb diet alone, she is at peace with also helping patients undergoing bariatric surgery.

“I know bariatric surgery is frowned upon by some in the low-carb community, but listen, these people are going to have the surgery whether we want them to or not. My role is to help them be successful no matter what they do.”Fortunately, the surgeon in the clinic fully supports low-carb eating so Dr. Palavecino’s pre-op and post-op support focuses on low-carb and intermittent fasting for the long-term.

“I say, ‘Listen, you can have the surgery and lose weight, but if you want to be successful for life you have to understand the changes that happen inside of you. I help them understand that if you only have a tiny space for a stomach, you have to fill it with the best food you can afford. It should be bacon and eggs — and not bread and cakes.”

“Do whatever she says”

Three years ago, when her first patients went back to their other doctors, like the local cardiologist, they would say: ‘Dr. P says I should eat more fat.’

Dr. Palavecino recalls: “The doctor would say, ‘I don’t think you heard her right; I don’t think she said that,” and the patients would go, ‘Yes, that’s what she said, we need to eat more fat.’”

Fast forward three years? “Now they’re saying, ‘You do whatever she says!'” Dr. Palavecino laughs.

Some patients come to her for medical weight loss with a history of failed gastric bypass surgery. They had the operation but eventually regained all the weight.

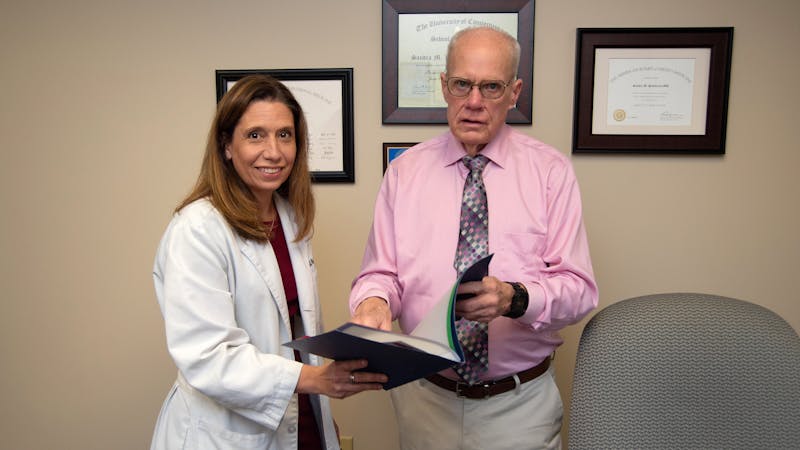

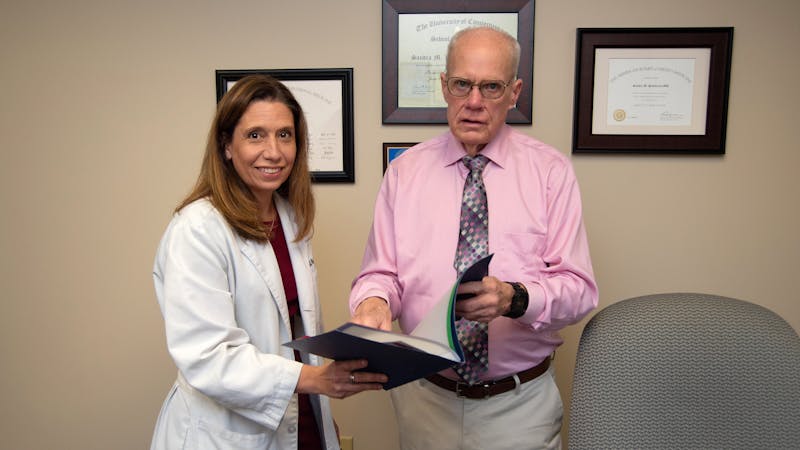

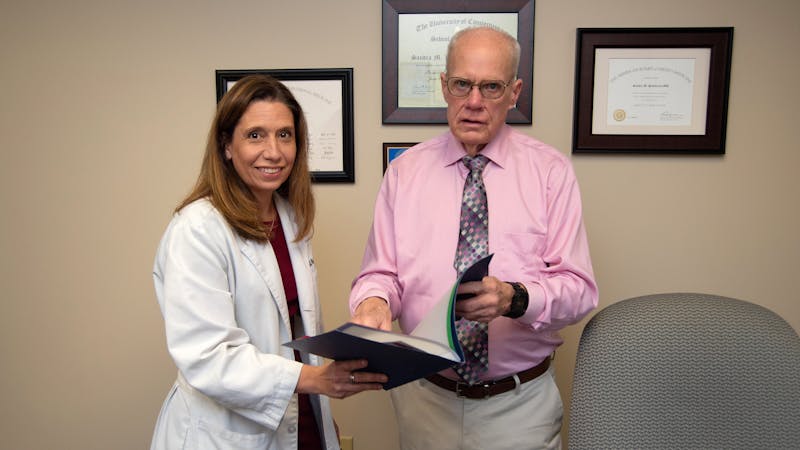

Craig Prettyman, 72, was one who regained every pound. With help from Dr. Palavecino, he’s now lost 190 pounds (86 kilos) and 32 inches (81 cm) from his waist. He follows a low-carb, no-sugar diet, with intermittent fasting and moderate exercise. He recently celebrated his three year-anniversary of joining the Nanticoke Weight Loss program.

“I have been dieting for 50 years. I would lose weight, but I could never maintain the weight loss,” Prettyman says. “I have now been able to maintain my desired weight for more than a year without hunger. To say [Dr. Palavecino] has changed my life is an understatement. I sincerely believe anyone can lose weight following her program.”

Photo by James Hill

Creating a weight loss register

Short-term weight loss is easy, says Dr. Palavecino. “It’s long-term maintenance that’s hard.”

How many of her initially successful patients were able to maintain long-term weight loss? Once patients leave the program, were they still following the low-carb diet?

Dr. Palavecino wasn’t sure. She decided to collect patient data; Prettyman was eager to help. She wrote up a questionnaire and found the names of 50 patients who’d been with her for more than 18 months. Prettyman tried to contact all 50, keeping their answers anonymous. Dr. Palavecino knew who participated, but not what they said.

Prettyman was able to get responses from 48 out of 50 patients. The results were very encouraging:

- 90% were still eating low carb

- 96% were fasting for at least 12 hours each day

- 92% still embraced the idea of increasing fat in their diet

- 96% said they were mindfully eating and only eating when hungry

- 63% had already achieved their weight loss goals

- 33% said they had not yet achieved their goals, but were on track to achieve them

- only 5% said they had not met their goal

- 34 pounds (15 kilos) was the average weight loss, but 11 of the 48 patients had lost more than 50 pounds (23 kilos)

Dr. Palavecino notes these results “look great” but a weight loss register presents skewed data. People who don’t do well get lost to follow up, drop out, or don’t respond. Still, this kind of success can be inspiring and motivating to others.

And indeed, word has spread. Before the coronavirus hit, the clinic had a three-month waiting list.

On a typical day, Dr. Palavecino sees six new patients and follows up with about 14 or 15 existing patients. The program also has group visits, running up to five groups a week with up to 10 patients each. The clinic also has a nurse practitioner and dietitian on staff, but Dr. P sees each patient.

“I think a big waiting list is terrible because if patients want help, they want it right away. But there’s only so much I can do in a day. One patient at a time is too slow for me. I want to help more.”Changing the Medicaid rules

Up until recently, the state-run Medicaid program, which provides medical coverage to low-income individuals, considered obesity treatment to be “cosmetic.”

That meant many people in the Seaford region could not access the obesity program on their insurance.

The region is surrounded by chicken farms, the state’s dominant agricultural commodity, and many people work in low-wage jobs in that industry and may have other jobs just to make ends meet. The site Data US notes that 30% of the population in Seaford is on Medicaid.

For months, Dr. Palavecino wrote letters and faxed the administrators of the Medicaid program asking for a meeting. In the early summer of 2019, she was granted a 30-minute session with the Medicaid director and deputy director. Her aim was to convince them obesity was a fundamental health issue that should be covered by Medicaid insurance.

Dr. Palavecino made a special trip to Wilmington, Delaware, for the meeting, armed with statistics about the burden of the obesity epidemic and data about the health improvements from weight loss.

She described some of the patients she had seen the day before and tallied how much weight the patients had collectively lost. The amount was in the hundreds of pounds.

“They just listened to me and said, ‘Doctor this is amazing. We didn’t even know you guys existed.'”A few months later, the Delaware Medicaid program announced that patients would have their insurance cover 13 consultations with a doctor for obesity treatment each year.

Was it Dr. Palavecino who convinced them? She’s not sure. Maybe they were considering options before the meeting and she happened to hit them at the right time?

However, the experience convinced her of two things: “First, advocating for your patients and making changes may not be as hard as you think. And, second, as horrible as politics look like right now, if you have something real for which you can show results, they will at least give you a 30-minute interview to present your case.”

Why do some struggle?

Granted, not every patient is successful. For some, the weight loss is slow, non-existent, or they lose some weight only to regain it back.

Dr. Palavecino calls these patients “the next frontier.” They are the ones who obesity doctors need to understand better and find more effective ways to help.

“For some patients, it’s so easy. You tell them about low-carb eating. They go, “I get it” and they lose weight. But others really struggle. We have to figure out the missing ingredient for those who are not successful. What more can we do to help them?”Dr. Palavecino believes that sugar and food addiction may be a significant issue for some patients who struggle, as well as emotional eating and underlying trauma in which food is used as comfort. She is studying this burgeoning area of obesity medicine to find “more tools.”

She recently signed up for Bitten Jonsson’s sugar-addiction training program for health professionals in order to become certified to use a screening tool, called the Sugar Use General Assessment Recording (SUGAR®), which assesses addiction and pathological use of sugar, flour, and processed food.

Dr. Palavecino has also signed up for conferences and programs that deal with food addiction and “the brain side of obesity.” The Diet Doctor site, including its sugar addiction course, is a great resource, too. She refers patients to Diet Doctor daily.

While some patients like more intricate, involved recipes and to count macros, Dr. Palavecino preaches keeping the diet as simple as possible. Dinner just needs to be a protein such as meat, fish, or eggs, plus a vegetable, and some olive oil or butter. That is how she and her family now eat. “It doesn’t need to be complicated. ”“I try to empower my patients to learn a simple way of eating that they can take with them anywhere, for the rest of their lives. There are no fancy restaurants or fancy supermarkets here in Seaford. There are no special keto products. But we do have great farmers’ markets and lots of access to chicken and eggs!”

“I want my colleagues and my patients to know that you don’t have to be in someplace like New York or Hollywood to be successful with low-carb eating. If you can do it in Seaford, Delaware, you can do it anywhere.”

—