A user guide to saturated fat

For decades, consuming saturated fat has been considered an unhealthy practice that can lead to heart disease. This is based mostly on the finding in experimental trials that replacing saturated fat with unsaturated fat lowers low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, and that LDL cholesterol itself is linked to heart disease.1

But is this harmful reputation warranted?2

Better quality research has demonstrated that saturated fat’s effect on heart disease is a lot more complicated. Factors that need to be considered include individual responses to saturated fat intake, food sources of saturated fat, and how the rest of the diet changes when a person increases their saturated fat intake.

Highlighting these points, 19 leading researchers concluded that evidence does not support the general advice to reduce saturated fat intake, and that the topic is far more nuanced than commonly reported.3 A similar article was also published in a major mainstream cardiology journal in 2020.4

All of this is further confounded by the fact that most studies combine all sources of saturated fat together. That means saturated fat from a steak is counted the same as saturated fat in cookies, cake or other baked goods, which have a combination of saturated fats, trans fats and sugars.

How can someone make sense of all this? This guide explains what is known about saturated fat, discusses the scientific evidence regarding its role in health, and explores whether we should be concerned about how much of it we eat.

Researchers have therefore had to rely on observational studies or short term trials using surrogate markers of heart disease such as LDL cholesterol. While many guidelines recommend lowering intake of saturated fats, this is largely based on lower quality epidemiology studies. Therefore there is a lot of uncertainty around how much saturated fat people should have in their diet.5

This guide is our attempt at summarizing what is known. It is written for adults who are concerned about saturated fat intake and their health, specifically their risk of heart disease or risk of dying prematurely. Discuss any lifestyle changes with your doctor. Full disclaimerFor even more details and relevant research on connected topics, see our guides to healthy fats, vegetable oils and cholesterol. Also see our list of core scientific studies related to heart disease, cholesterol and saturated fats.

First, what is saturated fat?

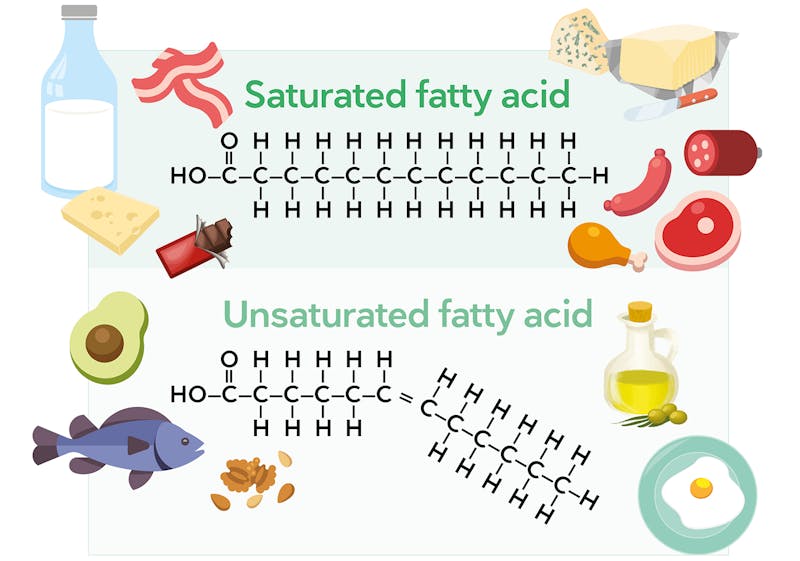

A fat (or fatty acid) is classified as saturated or unsaturated based on its molecular structure. Every fatty acid contains a chain of carbon and hydrogen atoms.

Saturated fats don’t have any double bonds between their chain of carbons, allowing more hydrogen atoms to be attached to the carbon atoms. This means they are “saturated” with hydrogens. This structure makes them solid at room temperature.

By contrast, an unsaturated fat contains at least one double bond between its carbon atoms — notice in the illustration fewer hydrogen atoms attached to the carbons with the double bond. This chain is now “unsaturated” with hydrogen atoms and remains liquid or semi-liquid at room temperature.

Learn more in our guide, Healthy fats on a low-carb diet.

Which foods contain saturated fat?

Saturated fats are found in both plant and animal products. The foods we eat contain a combination of saturated and unsaturated fats. For instance, although olive oil, nuts, and avocados are typically considered unsaturated fat sources, these foods provide some saturated fat as well.

Here are the amounts of saturated fat in some popular low-carb foods:

- 1 tablespoon (14 grams) coconut oil: 13 grams

- 3.5 ounces (100 grams) pork belly: 10-12 grams

- 3.5 ounces (100 grams) ribeye steak: 8-12 grams

- 1 ounce (30 grams) dark chocolate (70-85% cacao): 7-9 grams

- 1 tablespoon (14 grams) butter: 7 grams

- 1 ounce (30 grams) cheese: 5-7 grams

- 1 tablespoon (14 grams) tallow: 6 grams

- 1 tablespoon (14 grams) lard: 5 grams

- 1 ounce (30 grams) macadamia nuts: 4 grams

- 3.5 ounces (100 grams) chicken drumstick: 4 grams

- 1 medium avocado (200 grams): 4 grams

- 1 tablespoon (14 grams) heavy cream: 4 grams

- 1 tablespoon (14 grams) olive oil: 2 grams

Keep in mind that many other keto-friendly foods contain at least a small amount of saturated fat.

Saturated fat and health risks: the evidence to date

Guidance to reduce saturated fat is based on studies which show 1) a causal link between saturated fat and LDL cholesterol and 2) a causal link between LDL cholesterol and coronary heart disease.6 However, convincing evidence for a direct link between saturated fat and heart disease is lacking.

Let’s take a closer look at what systematic reviews of observational studies and intervention trials tell us about saturated fat intake and the risk of coronary heart disease (CHD), other diseases, and death from any cause.

- A 2009 meta-analysis of 28 cohort studies and 16 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) concluded “The available evidence from cohort and randomised controlled trials is unsatisfactory and unreliable to make judgment about and substantiate the effects of dietary fat on risk of CHD.”7

- A 2010 meta-analysis of 21 cohort studies found no association between saturated fat intake on CHD outcomes.8

- A 2014 systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies and randomized controlled trials found that the evidence does not clearly support dietary guidelines that limit intake of saturated fats and replace them with polyunsaturated fats.9

- A 2015 meta-analysis of 17 observational studies found that saturated fats had no association with heart disease, all-cause mortality, or any other disease.10

- A 2017 meta-analysis of 7 cohort studies found no significant association between saturated fat intake and CHD death.11

Two systematic reviews of clinical trials — considered the strongest, most reliable evidence — found that replacing saturated fats with unsaturated fats may slightly reduce the risk of heart attack and other cardiovascular events. In the latter review, this effect was found to apply only to men, however, and the intervention had no impact on total mortality or death from heart disease.12 Other extensive and similarly high-quality reviews have failed to establish any benefit.13

The 2012 Cochrane review of RCTs cited in the previous paragraph was updated in 2020, again finding a small reduction in cardiovascular events with lower saturated fat intake. As before, it also found no difference in cardiovascular death or all-cause death.14

An observational study of high-risk subjects from Italy, France, and Scandanavia reported a minimal association between saturated fat intake and progression of carotid intima-media thickness (CIMT, a measurement of subclinical vascular disease), but this association disappeared when all other potential variables were taken into account. The conclusion, therefore, was that there is no evidence that saturated fat intake causes a progression of vascular disease.15

Mente and colleagues published a large observational study that examined dietary patterns and lipid data from over 100,000 people in 18 countries around the world. Called the PURE study, its data analysis found that higher saturated fat intake was associated with beneficial effects on a number of heart disease risk factors, including higher HDL levels, lower triglyceride levels, and – what seemed to be the strongest predictor of CHD risk — a decreased ratio of ApoB (found in LDL particles) to Apo A (found in HDL particles). The study also found that replacing saturated fat with unsaturated fat improved some markers while making others worse, while replacing saturated fat with carbohydrates simply had an adverse effect on blood lipids.16

However, as with many epidemiology studies, this study had significant flaws, including not measuring trans fat and inadequate measurement of the quality of carbohydrate. It also measured dietary intake on one occasion, in contrast to most epidemiological studies which have serial dietary data collection points.

Finally, as noted in the introduction, recent data have demonstrated that we need to be much more nuanced when considering the effect of saturated fat on heart disease. We’ll explore the most important nuances next.

Replacing nutrients

The food or nutrient which replaces saturated fat determines whether the switch might be beneficial, neutral or even harmful.17

If you think about the studies which reduced saturated fat intake – what did they replace it with? Carbohydrates (such as whole grains vs. refined grains), unsaturated fats, or protein? This really matters.

It’s now clearer that replacing saturated fat with refined carbohydrates does not improve heart disease risk, whereas replacing saturated fat with polyunsaturated fat might, although the evidence is not strong.18 This nuance could explain some of the conflicting results from meta-analyses.

There may be little point recommending a person reduce their saturated fat intake if they just end up replacing it with sugary cereals and white bread.

Food sources of saturated fat

A variety of foods are rich sources of saturated fat, including red meat, butter, cheese and coconut oil. Most studies combine all sources of saturated fat together. That means saturated fat in cream is counted the same as saturated fat in yogurt or cheese.

Many foods, including meat and dairy, contain other nutrients and non-nutrient components which can influence heart disease risk, such as probiotics, magnesium, potassium and vitamin D. They also contain other types of fats.

For instance, most beef products have nearly equal amounts of saturated and monounsaturated fats. Therefore, even though meat, yogurt and butter are relatively high in saturated fat, their effects on heart disease may be divergent due to these “confounding” factors.

Researchers report that myristic acid (a saturated fat found in many foods like coconut oil, palm kernel oil, butter, cream, cheese and meat) has a greater effect on both LDL and HDL cholesterol levels than most other saturated fats.19

On the other hand, there are a number of controlled studies showing that cheese is much less likely to raise LDL-cholesterol than is butter.20 Further, dairy fat from yogurt and cheese may be protective against heart disease, as suggested by both observational studies and randomized controlled trials.21

As leading scientists claimed in their 2020 review paper, we should be discussing health implications of specific foods, rather than lumping them all together as “saturated fats.”22

Overall diet

As described above, the whole diet is important. Most people eating a high-carb diet get their carbs from refined grains and sugars, which themselves may be harmful to health. If a low-carb (but high-saturated fat) diet helps them to omit the harmful types of carbs and consume more non-starchy vegetables, then this could be a net health benefit.

In other words, processed foods that are manufactured to replace naturally occurring saturated fats with refined carbs and sugars are rarely a healthier choice.

What do foods’ saturated fat levels mean for the typical low-carber?

Someone following a typical low-carb or keto diet might consume 30 or more grams of saturated fat most days, which is significantly above the levels currently advised by the US Dietary Guidelines for Americans (about 22 grams a day) and American Heart Association (13 grams).

Is that a problem? We don’t know for sure, but for many people, probably not. In general, the effect of one nutrient on any outcome is very small.23

It’s also important to consider all other factors which might influence a person’s risk of heart disease, and how an increase in saturated fat in the context of a low-carb diet might affect them.

For example, if by eating a low-carb diet (which happens to be high in saturated fat) a person is able to lose 10 lbs (4.5 kilos) of weight, improve their blood sugars, and lower their blood pressure, a small rise in LDL cholesterol should be unlikely to result in a net increase in heart disease risk.

In fact, weight loss intervention studies that have used low-carb, high-fat diets (including saturated fat) have shown on average no significant change in LDL cholesterol.24 Instead, they have shown an overall improvement in risk markers for heart disease.25 This is why considering individual responses is important.

In summary, for many or even most people, increasing saturated fat intake in the context of a healthy low-carbohydrate diet should have a negligible impact on their heart disease risk.

Videos about saturated fat

Conclusion

An across-the-board recommendation to limit your consumption of saturated fat to a small percentage of daily calories isn’t based on sound scientific evidence. In general, focusing on your whole diet is a better health strategy than limiting a single nutrient like saturated fat.

Many low-carb whole foods that provide valuable nutrients and help you feel full — such as meat and full-fat dairy products — are also rich in saturated fat. For people with metabolic conditions that can be improved with a low-carb diet, the benefits of these foods may be more important than a risk that may or may not exist.26

On the other hand, the relationship between saturated fat intake and LDL-cholesterol concentration, particle number, and particle size seems to vary quite a bit among individuals, particularly when monitoring the response to a low-carb diet. It’s important that both you and your health care provider are aware of this.

You can read more about LDL cholesterol in our evidence based guides:

Low carb LDL hyper-responders

Is elevated LDL cholesterol harmful?

Cholesterol and low carb diets

Start your FREE 7-day trial!

Get instant access to healthy low-carb and keto meal plans, fast and easy recipes, weight loss advice from medical experts, and so much more. A healthier life starts now with your free trial!

Start FREE trial!A user guide to saturated fat - the evidence

This guide is written by Franziska Spritzler, RD and was last updated on June 19, 2025. It was medically reviewed by Nicola Guess, RD MPH PhD on April 30, 2021 and Dr. Michael Tamber, MD on March 22, 2022.

The guide contains scientific references. You can find these in the notes throughout the text, and click the links to read the peer-reviewed scientific papers. When appropriate we include a grading of the strength of the evidence, with a link to our policy on this. Our evidence-based guides are updated at least once per year to reflect and reference the latest science on the topic.

All our evidence-based health guides are written or reviewed by medical doctors who are experts on the topic. To stay unbiased we show no ads, sell no physical products, and take no money from the industry. We're fully funded by the people, via an optional membership. Most information at Diet Doctor is free forever.

Read more about our policies and work with evidence-based guides, nutritional controversies, our editorial team, and our medical review board.

Should you find any inaccuracy in this guide, please email andreas@dietdoctor.com.

World Health Organization 2016: Effects of saturated fatty acids on serum lipids and lipoproteins:a systematic review and regression analysis [systematic review of randomized controlled trials; strong evidence]

Much of the concern with saturated fat can be traced back to the diet-heart hypothesis first proposed in the 1950s by American scientist Ancel Keys. He promoted the theory that dietary fat raises cholesterol levels, thereby increasing the risk of heart disease. After traveling to Europe and conducting informal surveys in different populations there between 1951 and 1952, Keys published a paper suggesting that as a country’s intake of fat increased, its rates of coronary heart disease (CHD) and related deaths likewise increased.

American Journal of Public Health and the Nation’s Health 1953: Prediction and possible prevention of coronary disease [observational research; very weak evidence]

Importantly, this was based entirely on observational data, which is considered weak evidence unless correlations are strong and have been repeatedly duplicated in other studies. Even then, this type of research can only show that a behavior and an outcome are associated but not that the behavior causes the outcome.

Modern systematic reviews and meta-analyses of RCTs have often failed to find a link between saturated fat intake and heart disease or death.

Open Heart 2015: Evidence from randomised controlled trials did not support the introduction of dietary fat guidelines in 1977 and 1983: a systematic review and meta-analysis [strong evidence]

↩BMJ 2018: Dietary fat and cardiometabolic health: evidence, controversies, and consensus for guidance [overview article; ungraded] ↩

British Medical Journal 2019: WHO draft guidelines on dietary saturated and trans fatty acids: time for a new approach? [overview article; ungraded evidence] ↩

Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2020: Saturated fats and health: A reassessment and proposal for food-based recommendations: JACC State-of -the-Art Review [overview article; ungraded] ↩

Nutrition Journal 2016: The effect of replacing saturated fat with mostly n-6 polyunsaturated fat on coronary heart disease: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials [strong evidence]

BMJ Evidence-Based Medicine 2019: Fat or fiction: the diet-heart hypothesis [overview article; ungraded evidence]

British Medical Journal 2019: WHO draft guidelines on dietary saturated and trans fatty acids: time for a new approach? [overview article; ungraded evidence] ↩

American Journal of cardiology 1984: Lipid research clinics coronary primary prevention trial: Results and implications [randomized trial; moderate evidence] ↩

The study concluded that there isn’t sufficient evidence from RCTs to correlate saturate fat intake with an increased risk of CHD. However, in a post-script to the study, they reported that a late-breaking review of observational cohort studies (a very weak level of evidence) suggested a small benefit to replacing saturated fat with polyunsaturated fat. However, we caution against over-interpreting these data given the very weak quality.

Annals Nutrition & Metabolism 2009: Dietary fat and coronary heart disease: Summary of evidence from prospective cohort and randomised controlled trials [moderate evidence] ↩

The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2010: Meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies evaluating the association of saturated fat with cardiovascular disease [meta-analysis of nutritional epidemiology studies; very weak evidence] ↩

Annals of Internal Medicine 2014: Association of dietary, circulating, and supplement fatty acids with coronary risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis [meta-analysis of nutritional epidemiology studies and RCTs; weak evidence] ↩

British Medical Journal 2015: Intake of saturated and trans unsaturated fatty acids and risk of all cause mortality, cardiovascular disease, and type 2 diabetes: systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies [meta-analysis of nutritional epidemiology studies; very weak evidence] ↩

British journal of sports medicine 2017: Evidence from prospective cohort studies does not support current dietary fat guidelines: a systematic review and meta-analysis [meta-analysis of nutritional epidemiology studies; very weak evidence] ↩

These two systematic reviews showed a slight benefit of replacing saturated fatty acids with PUFAs.

Public Library of Science Medicine 2010: Effects on coronary heart disease of increasing polyunsaturated fat in place of saturated fat: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials [strong evidence]

The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2012: Reduced or modified dietary fat for preventing cardiovascular disease [systematic review of randomized trials; strong evidence] ↩

British Medical Journal 2013: Dietary fatty acids in the secondary prevention of coronary heart disease: a systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regression[strong evidence]

British Medical Journal 2016: Re-evaluation of the traditional diet-heart hypothesis: analysis of recovered data from Minnesota Coronary Experiment (1968-73) [systematic review of randomized trials; strong evidence]

Nutrition Journal 2017: The effect of replacing saturated fat with mostly n-6 polyunsaturated fat on coronary heart disease: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials[strong evidence]

↩Cochrane Database of Systemic Reviews 2020: Reduction in saturated fat intake for cardiovascular disease [systematic review of randomized trials; strong evidence] ↩

Scientific Reports 2021: Intake of food rich in saturated fat in relation to subclinical atherosclerosis and potential modulating effects from single genetic variants[observational study; very weak evidence] ↩

The Lancet Diabetes and Endocrinology 2017: Association of dietary nutrients with blood lipids and blood pressure in 18 countries: a cross-sectional analysis from the PURE study [observational study; very weak evidence]

↩Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2015: Saturated fats compared with unsaturated fats and sources of carbohydrates in relation to risk of coronary heart disease: A prospective cohort study [nutritional epidemiology study; very weak evidence] ↩

At least in the setting of a high-carb diet, studies suggest this may be the case.

American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2009: Major types of dietary fat and risk of coronary heart disease: a pooled analysis of 11 cohort studies [nutritional epidemiology study with HR < 2, very weak evidence] ↩

The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 1997: Individual fatty acid effects on plasma lipids and lipoproteins: human studies [overview article; ungraded]

Journal of Lipid Research 1997: Effects of medium chain fatty acids (MCFA), myristic acid, and oleic acid on serum lipoproteins in healthy subjects [non-randomized trial; weak evidence] ↩

American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2011: Cheese intake in large amounts lowers LDL-cholesterol concentrations compared with butter intake of equal fat content [randomized trial; moderate evidence]

European Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2005: Dairy fat in cheese raises LDL cholesterol less than that in butter in mildly hypercholesterolaemic subjects [randomized trial; moderate evidence]

↩Advances in Nutrition 2019: Effects of full-fat and fermented dairy products on cardiometabolic disease: Food is more than the sum of its parts [overview article; ungraded] ↩

Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2020: Saturated fats and health: A reassessment and proposal for food-based recommendations: JACC State-of -the-Art Review [overview article; ungraded] ↩

Cochrane Reviews 2015: Reduction in saturated fat intake for cardiovascular disease [systematic review of randomized trials; strong evidence] ↩

Nutrition Reviews 2019: Effects of carbohydrate-restricted diets on low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels in overweight and obese adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis

[systematic review of randomized trials; strong evidence] ↩American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2021: Effect of carbohydrate-restricted dietary interventions on LDL particle size and number in adults in the context of weight loss or weight maintenance: a systematic review and meta-analysis

[systematic review of randomized trials; strong evidence]Nutritional Reviews 2019: Effects of carbohydrate-restricted diets on low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels in overweight and obese adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. [systematic review of randomized trials; strong evidence]

Cardiovascular Diabetology 2018: Cardiovascular disease risk factor responses to a type 2 diabetes care model including nutritional ketosis induced by sustained carbohydrate restriction at 1 year: an open label, non-randomized, controlled study [weak evidence] ↩

Lipids 2010: Limited effect of dietary saturated fat on plasma saturated fat in the context of a low carbohydrate diet [randomized trial; moderate evidence]

Public Library of Science One 2014: Effects of step-wise increases in dietary carbohydrate on circulating saturated fatty acids and palmitoleic acid in adults with metabolic syndrome [non-randomized trial; weak evidence] ↩