Evidence based

How to improve and measure your body composition

You may have started a new diet and exercise program and feel you are making progress. But when you step on the scale, nothing has changed. Does that mean your efforts “aren’t working?”Not necessarily.

Or, maybe your doctor tells you that your body mass index (BMI) is high. Do you know what that means, and is it necessarily bad news?

It depends.

The scale and BMI are rudimentary tools for gauging your overall body composition, meaning they don’t tell you enough to determine if you are at a healthy weight.

Here’s an example. A professional athlete may be six feet tall (183 cm), weigh 225 pounds (102 kg), and be in fantastic physical condition with a 32-inch waist (81 cm) and bulging muscles. A busy doctor may be six feet tall and weigh 225 pounds with a 39-inch waist (99 cm) and a bulging midsection.

They have the same weight and the same BMI, but very different health assessments. What’s different? The two men have different amounts of muscle tissue and fat mass. The athlete has a healthy body composition. The doctor perhaps does not.

Knowing your body composition gives you a better picture of your overall health than just knowing weight or BMI.

Key takeaways

Improving your body composition means eliminating excess fat mass and increasing lean mass by building muscle, which helps improve metabolic health parameters like blood sugar, insulin resistance, and blood pressure.Sustainably decreasing caloric intake is the best way to reduce fat mass, and resistance training is likely the best form of exercise for building muscle mass.

Higher protein diets help you maximize body composition improvement from resistance training.

Start your FREE 30-day trial!

Get instant access to healthy low carb and keto meal plans, fast and easy recipes, weight loss advice from medical experts, and so much more. A healthier life starts now with your free trial!

Start FREE trial!What is body composition and why is it important?

Summary

- Body composition refers to the absolute or relative amounts of fat and lean mass.

- Muscle, bones, and water make up lean mass.

- Increasing lean body mass can reduce the risk of many chronic diseases and can significantly improve health and functional status.

Or, watch a summary of this guide where you’ll learn how to improve and measure your body composition

Body composition refers to the amount of fat, muscle, bone, and water that contributes to your total weight. Body composition can be expressed as a percentage (like body fat percentage) or an absolute amount (like pounds of muscle mass). Muscle, bone, and water are frequently combined and referred to as lean body mass, which differentiates them from fat mass.

As we describe in our healthy weight loss guide, not all weight loss is “healthy.” Ideally, losing weight means losing mostly fat mass — not lean mass — with minimal reduction in your resting metabolic rate.

For better health, most people want to lose fat mass and preserve or gain lean mass. Preserving muscle and bone helps prevent sarcopenia (muscle loss), frailty, and osteopenia (bone loss), in addition to improving the ability to do everyday tasks.

Higher muscle mass with lower fat mass may also be related to a lower risk of heart disease, cancer, and dementia, and may be a predictor of longevity.

For some people, improving body composition has nothing to do with losing weight. Numerous studies have called attention to the health risk of having a normal weight while also having a number of metabolic risk factors more commonly associated with obesity. This is often referred to as “normal weight obesity” or colloquially as “thin on the outside and fat on the inside (TOFI).”

How to achieve better body composition

Summary

- A simple definition of improved body composition is decreased fat mass with increased or preserved muscle mass.

- A high protein, low carb diet may be one of the most effective ways to reduce fat mass while maintaining or increasing lean mass.

- Intermittent fasting and other means of calorie reduction may also help lower fat mass but should be augmented with resistance training to preserve lean mass.

- Resistance training exercise is the most effective way to increase lean body mass.

- Sustainably reducing your calories to lower excess body fat.

- Getting enough protein to promote muscle growth.

- Using exercise to stimulate your muscles to build lean mass.

While there is more than one way to accomplish these goals, here are the best tips, backed by science, to improve your body composition.

Nutrition

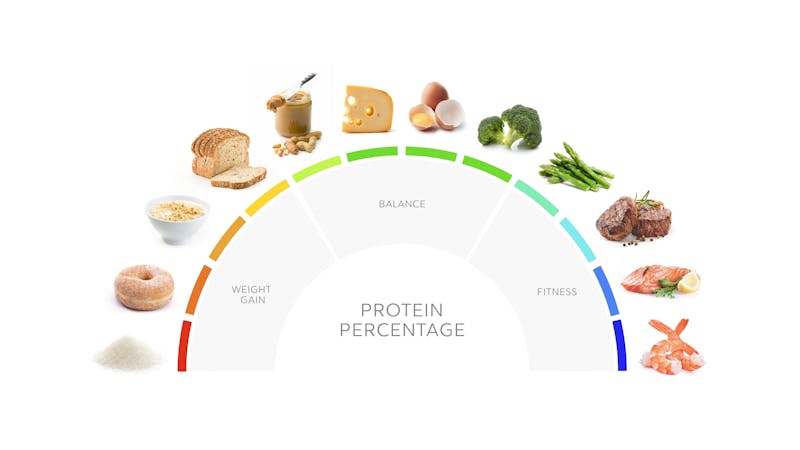

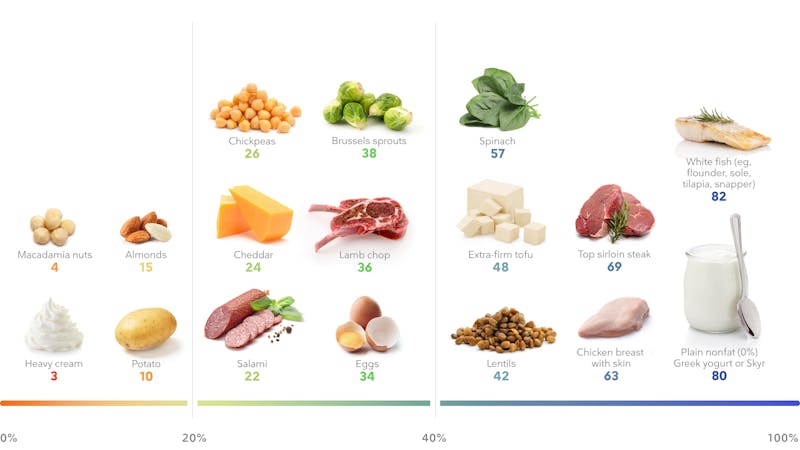

Nutrition is vital for improving body composition. What you eat and how much you eat can have a significant impact on losing fat mass and gaining muscle mass. Here are some of the best ways to eat, according to science, to help you improve your body composition.High protein for building muscle

Eating more protein than the average American helps maximize the muscle-building benefits of resistance training, and people who engage in resistance training or endurance-type exercise need more protein than do people of the same height and weight who are sedentary.

How much more? For the average person, the maximal muscle-building effect likely occurs around 1.6 grams per kilogram of reference body weight per day.

Use this simple chart to find out what your minimum daily protein target should be, based on your height.

| Height | Women | Men |

|---|---|---|

| Under 5’4″ ( < 163 cm) | 90 grams | 105 grams |

| 5’4″ to 5’7″ (163 to 170 cm) | 100 grams | 110 grams |

| 5’8″ to 5’10” (171 to 178 cm) | 110 grams | 120 grams |

| 5’11” to 6’2″ (179 to 188 cm) | 120 grams | 130 grams |

| Over 6’2″ (188 cm +) | 130 grams | 140 grams |

Low carb for fat loss

In addition to increasing protein, decreasing carbs can have a beneficial effect on body composition. Numerous studies report improved body composition with a low carb diet.

In 2019, researchers from Virta Health published a two-year study of the keto diet reporting a 15% reduction in abdominal fat.

Other studies show a low carb diet leads to greater loss of fat mass than a low fat diet.

And another study reports an 11% reduction in intra-abdominal fat for low carb eaters compared to a 1% reduction for low fat dieters.

Finally, one randomized controlled trial reports decreased fat mass and maintenance of lean mass in women following a ketogenic diet.

No problem!

Calorie reduction for fat loss

Improving body composition involves gaining or preserving muscle and losing fat mass. As we have shown, eating protein can significantly improve muscle mass. Low carb eating can help you lose body fat, as we detailed in the previous section. But so too can practically any means of reducing your calorie intake.

The key, however, is reducing calories in a way that helps you lose fat mass without also losing muscle mass.

In some studies, calorie restriction leads predominantly to fat-mass loss. One randomized trial reports that 12 weeks of calorie restriction reduced fat mass by 11 pounds (5 kilos) and visceral fat by 16%.

Fortunately, there are other ways to naturally reduce caloric intake, such as eating a higher protein diet.

Protein may help you eat less because it can reduce appetite and prevent overeating by triggering the release of hormones that promote feelings of fullness and satisfaction.

And since low carb diets also help people spontaneously eat fewer calories, it makes sense that combining low carb and high protein is a recipe for successful fat loss and muscle gain.

Low carb recipes

Related content

Short-term intermittent fasting for fat loss

Time-restricted eating or short-term intermittent fasting, of less than 36 hours, can help with fat-mass loss with minimal to no loss of muscle mass. However, with longer fasting periods, there is a concern about losing muscle mass.

One study shows that six weeks of alternate-day fasting led to a 7% overall weight loss, most of it fat mass.

Another randomized trial reports more significant fat-mass loss with intermittent calorie restriction than with traditional dieting.

And an analysis of eight studies looking at time-restricted eating or alternate-day fasting plus resistance training demonstrates maintenance or even an increase in muscle mass.

Although not all studies agree. For instance, one randomized controlled trial that did not dictate how much or what the subjects ate didn’t demonstrate a benefit for lean mass in those doing 16:8 time-restricted eating.

Older studies with longer fasting periods report a negative nitrogen balance — a marker of muscle loss.

What should we make of this evidence? Time-restricted eating and short-term intermittent fasting may help reduce calories without significant muscle-mass loss. But longer fasts may lead to muscle-mass loss, and what you eat during your “eating window” may impact your body-composition response. Given the limited amount of research in this field, we need studies that assess the long-term effects of intermittent fasting on body composition.

What to avoid to improve body composition

When looking to improve your body composition, what you don’t eat may be just as important as what you do eat. Here are three things to avoid to improve your body composition.

Alcohol provides calories without nutrition which can make it difficult to sustainably reduce caloric intake. In addition, alcohol can diminish inhibitions and self control, leading to excessive calorie consumption.

Sugar provides calories without nutrition and stimulates the brain’s reward center, encouraging you to eat more and stimulating your cravings.

Engineered foods like chips, crackers, and treats are designed to make you want more. They tend to be high in fat and carbs, with little protein or nutrition. Their satiety index is very low, and thus you can easily overeat them.

Summary

High protein diets are most beneficial for adding muscle mass. High protein, low carb diets are also beneficial for losing fat mass and improving satiety.Other dietary approaches that reduce calories, including intermittent fasting, may also improve body composition, but too much calorie restriction for too long may negatively impact muscle mass.

Exercise

In addition to proper nutrition, exercise can be a powerful tool for improving body composition. Here’s what science has to say about the best exercises.

Resistance training

Resistance training may be the most impactful intervention to increase lean body mass — including both muscle and bone mass.

Other forms of exercise — such as aerobic exercise like walking and jogging — are helpful for cardiovascular fitness and can improve blood sugar and blood pressure, but resistance training is superior when it comes to building muscle.

What does resistance training mean? Many people think it means going to the gym and pumping heavy iron alongside bodybuilders and muscle-bulging athletes.

That is not the case.

Resistance training means moving your muscles against resistance. That could mean using your body weight as resistance (such as squats or wall pushups), using elastic bands as resistance, or using two-pound weights.

As long as you continue to challenge your muscles, they will maintain or grow. Unlike fat loss, which happens across your whole body, building muscle with resistance training has a very targeted effect. If you only work your arms, only your arms will gain muscle and your legs will remain unaffected.

Here are some helpful tips to get started with resistance training:

Emphasize safety first

The last thing you want is to get injured and swear off resistance training as too dangerous. If you can, work with a personal trainer until you are comfortable on your own.

Start low and build slow. The ultimate goal may be to challenge your muscles with higher levels of resistance, but there’s no hurry to get there. Start with a resistance level you can do for 15 reps, but stop at 12 reps. Safety first.

Pro tip: Consider every exercise as an exercise for your stomach, back, and glute muscles (the ones you sit on). If you keep your glutes and lower abdominal muscles engaged for all your exercises, it helps build stability and can decrease the strain on your lower back and other sensitive muscle groups.

Work multiple muscle groups

Make sure to work multiple muscle groups rather than focusing on just one. Bicep curls work one particular muscle group — your biceps. But a squat with a bicep curl and shoulder press is a complex movement that works almost your whole body — your quads, glutes, biceps, core, and deltoids.

Plus, complex movements are more functional and will provide you with the real-world strength you need for life. They help you become that rare 80-year-old who can put their own luggage in the overhead bin.

Gradually increase the resistance

You may want to aim for lifting the heaviest resistance that you safely can for eight reps for two sets separated by a short rest. A “rep” is how many repetitions you can perform an exercise without resting. For example, one pushup equals one rep. A set is how many times you can repeat a number of reps, usually separated by a brief rest.

If you start as we suggested above — lifting a weight you can lift for 15 reps but stopping at 12 — you can gradually increase the resistance and lower the reps until you are nearing your max effort on the eighth repetition.

Just remember to engage your core with every rep! This is especially important as the weight increases.

Use the time you have

Can you commit 30 minutes to resistance training three days per week? Great! That may be all you need to see improvements.

Do you only have 10 minutes twice per week? That’s OK, too.

One important rule is “something is better than nothing.” Don’t fall into the trap of thinking it isn’t worth exercising if you can’t do a minimum amount of time or number of days. Yes, it may be better to exercise three days per week than once per week, but don’t get discouraged! One session is better than no exercise.

Don’t forget to rest

Building muscle mass requires stressing the muscle and then letting it recover and heal. That means you should aim for three days per week with an active rest day between each resistance training session.

Other exercises

The best training program may be a combination of resistance training three days per week with cardio or intervals on three days, with a day off that might include stretching or mobility work.

And remember, both walking and running are considered “weight-bearing exercises” and can improve your lower-body bone mass. Just don’t ignore your upper-body strength!

High-intensity interval training is also helpful for fat-mass loss and you can include it as part of your training program. However, some studies suggest HIIT may not be suitable for an initial weight loss plan for those unfamiliar with interval training.

For more details about what exercise regimen is best for you, see our detailed guide on exercise and health.

And to learn more about bone health, see our dedicated guide on low carb diets and bone health.

How to measure body composition

You can measure your body composition in many different ways — from expensive, complex scans to simple at-home tests requiring nothing more than a tape measure. Here are some of the most common methods and our recommendations for which you may want to consider.

Waist circumference

Perhaps the easiest and least technical way to estimate your body composition is measuring your waist circumference. Since the most important weight to lose is the weight around your middle, known as “belly fat,” improving your waist circumference can have a meaningful impact on your health.

Greater abdominal circumference in relation to height (waist-to-height ratio) is predictive of an increased risk of diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular disease and overall mortality, even in people of normal weight.

To get your waist-to-height ratio, just divide your waist measurement by your height. A waist-to-height ratio less than 0.5 indicates good insulin sensitivity, while a number higher than 0.5 indicates worsening insulin resistance.

You don’t even need a tape measure. Just take a piece of string! The length of string around your waist should be, at most, half your height. If your waist is larger than half your height, you likely have insulin resistance.

One of the great strengths of this measurement is that your ethnicity doesn’t matter, nor does it matter whether you are male or female, young or old, short or tall, muscular or wiry — a number higher than 0.5 indicates increased risk.

Selfies

Another simple way of tracking your body composition is taking selfies to track your physical appearance. Make sure you take the pictures in the same location, time of day, and zoom. You can track the size of your abdomen and the definition of your muscles.

Even if your weight isn’t changing much, if you see your abdomen getting smaller and your muscles getting bigger or more defined, then you are likely improving your body composition.

And, no, you don’t need to share your selfies on social media! Just because many like to make their journey public doesn’t mean you have to. Feel free to put the pictures in a private file and keep them locked away for only you to see.

Dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DEXA)

A DEXA scan uses low dose radiation and accurately detects your amount of lean mass and fat mass, the amount of visceral fat, and the density of your bones.

Given the low-dose radiation involved, most people suggest waiting at least 3-6 months between DEXA scans.

Just be sure that you’re getting a DEXA scan that assesses body composition. Most routine DEXA scans are ordered only to look at bone density.

When considering the combination of accuracy and detailed information, a DEXA scan may be the best choice, although cost can be a barrier.

Pros: Most accurate and detailed body composition information

Cons: Not for home use, small radiation dose, cost, and availability

Bioimpedance scales

Bioimpedance scales provide an estimate of fat-free mass and fat mass by using a small electric current to measure the “resistance” of your body tissue.

However, most home scales measure body composition in your lower body only, which limits their utility as much of the concerning fat mass is in the abdomen and trunk. Some have handles you can hold to also measure your upper body, but these are more expensive and usually located only at gyms or personal training centers.

But even these more expensive scales are affected by non-standardization of body position, recent exercise, and hydration status. This means that checking your body composition on one of these scales before and after your workout could yield different results.

Bioimpedance scales are not as accurate as DEXA scans but can be used to track trends over time. For instance, an accurate DEXA may show you to have 30% body fat with much of it centered around your abdomen and trunk, while the bioimpedance scale may say you have 20% body fat, as it misses much of the obesity around your middle. But if your bioimpedance numbers are dropping over time, you can still use that to gauge improvement.

These scales are best for people who want to track changes in daily or weekly measurements, but it may be worth adding a DEXA once a year to follow more accurate, absolute measurements.

Pros: Easy to get for home use

Cons: Less accurate than other measurements

Hydrostatic weight

For this one, you need to get wet.

Here’s how it works. First, you weigh yourself on dry land. Then you sit on a scale, submerge yourself underwater and blow out as much air as you can. The result is the difference between your dry weight and your underwater weight, which can help estimate your fat mass and fat-free mass.

This type of measurement can’t differentiate between bone, muscle, and water which all make up the fat-free mass. Nor can it tell you where your fat mass is distributed — visceral, abdominal, etc. But it is an easy way to accurately measure your total fat mass — as long as you don’t mind getting wet.

Pros: No radiation, quick test, and good test-to-test accuracy

Cons: You have to get wet! Not for home use, and may be difficult to find access to the specialized underwater scale

Air Displacement Plethysmograph (ADP)

Another device rising in popularity is the BOD POD, a type of ADP that measures your body’s volume by measuring the amount of air your body displaces when in a specialized measuring chamber.

It provides results similar to hydrostatic weight — it reports fat mass and fat-free mass — but it doesn’t give as much detail as a DEXA.

Also, if you are claustrophobic, a BOD POD may not be the right test for you as you have to spend several minutes in an enclosed chamber (although there is a window to see out of which does help some with mild claustrophobia).

Cons: Not for home use, may be limited availability, cost, and difficult for those with claustrophobia

Others

Other body composition tests tend to not be as accurate or practical. For instance, measuring skin folds with manual calipers rely on general equations that may be less accurate than other measurements and have significant test-to-test variability.

Other imaging studies, like MRIs or CTs, are expensive and have very limited availability. They are mostly used for research purposes and are impractical and less available for the general public.

Summary

Easiest: Waist circumferenceMost accurate: DEXA

Best for regular home use: Bioimpedance scales

Best of the rest: Hydrostatic weight and BOD POD if they are easily available

The best way to improve your body composition

Improving body composition includes decreasing fat mass and increasing lean body mass — muscle and bone mass.

Sustainable calorie reduction has the strongest evidence for fat-mass loss.

A combination of a low carb, high protein diet with resistance training may be the most effective for sustainably losing fat mass and maintaining muscle mass. Adding cardio or HIIT exercise can further help with losing fat mass.

Resistance training and higher protein diets (around 1.6 grams per kilo of ideal body weight per day) have the best evidence supporting their role in improving muscle mass.

Now you should have all the information needed to get started improving your body composition today!

Start your FREE 30-day trial!

Get instant access to healthy low carb and keto meal plans, fast and easy recipes, weight loss advice from medical experts, and so much more. A healthier life starts now with your free trial!

Start FREE trial!