When we eat is as important as what we eat – and this is why

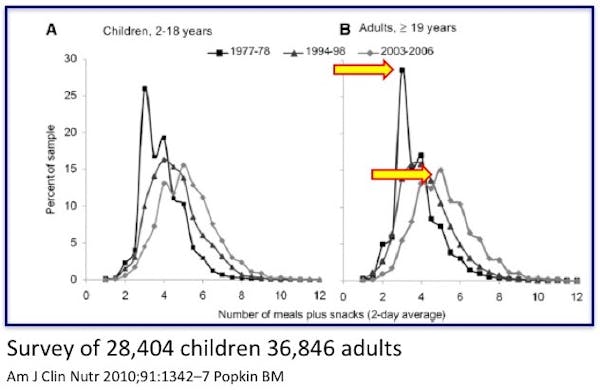

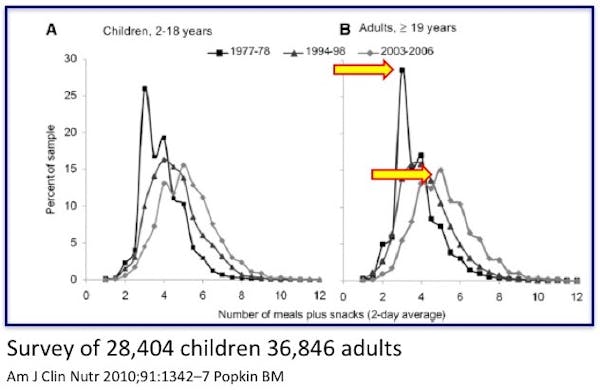

There have been two main changes in dietary habits from the 1970s (before the obesity epidemic) until today. First, there was the change in what we were recommended to eat. Prior to 1970, there was no official government sanctioned dietary advice. You ate what your mother told you to eat. With the publication of the Dietary Guidelines for Americans, we were told to cut the fat in our diets way down and replace that with carbohydrates, which might have been OK if it was all broccoli and kale, but might not be OK if it was all white bread and sugar.

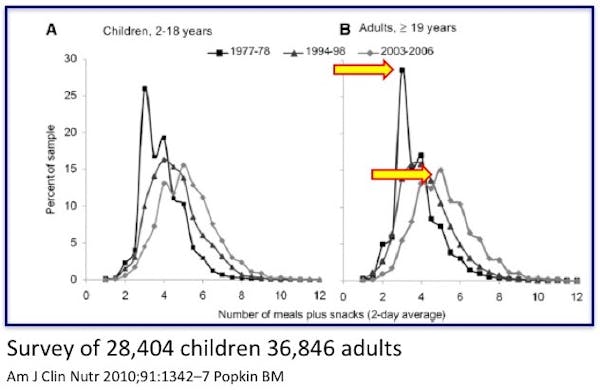

By 2004, the world had changed. Most people were now eating almost 6 times per day. It is almost considered child abuse to deprive your child of a mid-morning snack or after-school snack. If they play soccer, it somehow became necessary to give them juice and cookies between the halves. We run around chasing our kids to eat cookies and drink juice, and then wonder why we have a childhood obesity crisis.

How frequently do we eat?

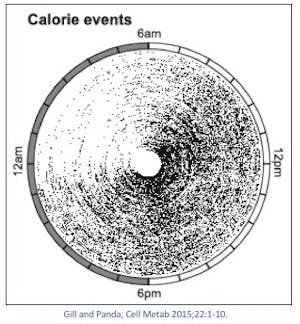

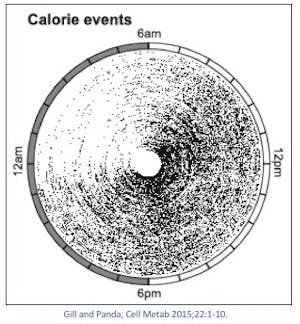

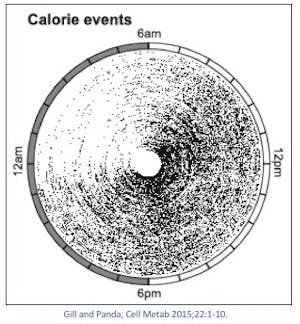

The median daily intake duration (the amount of time people spent eating) was 14.75 hours per day. That is, if you started eating breakfast at 8 am, you didn’t, on average, stop eating until 10:45! Practically the only time people stopped eating was while sleeping. This contrasts with a 1970’s era style of eating at 8 am breakfast and dinner at 6:00, giving a rough eating duration of only 10 hours. The ‘feedogram’ shows no let up in eating until after 11pm. There was also a noticeable bias towards late night eating, as many people are not hungry in the morning. An estimated 25% of calories are taken before noon, but 35% after 6pm.

When those overweight individuals eating more than 14 hours per day were simply instructed to curtail their eating times to only 10-11 hours, they lost weight (average 7.2 pounds – 3 kg) and felt better even though they were not instructed to overtly change what they ate, only when they ate.

Eating in the morning vs. evening

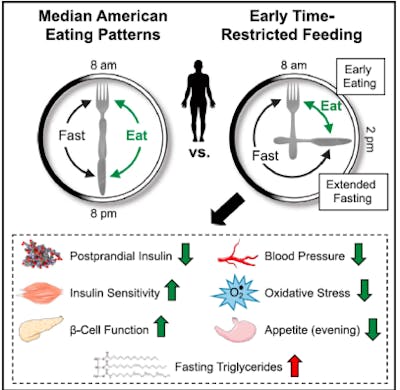

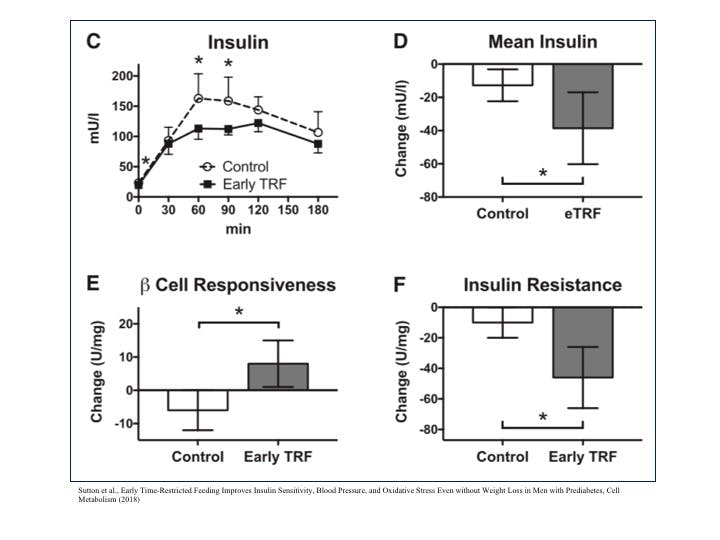

The circadian rhythm, as I’ve discussed previously, suggests that late night eating is not optimal for weight loss. This is because excessive insulin is the main driver of obesity, and eating the same food early in the day or late at night have different insulin effects. Indeed, studies of time restricted eating mostly show benefits from reducing late night eating. So it makes sense to combine two strategies of meal timing (circadian considerations and time restricted eating) into one optimal strategy of eating only over a certain period of the day, and only during the early daytime period. Researchers called this the eTRF (early Time Restricted Feeding) strategy.

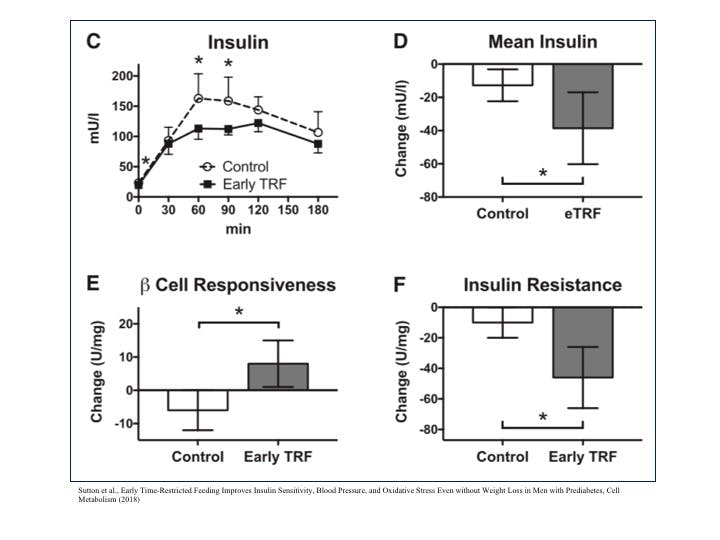

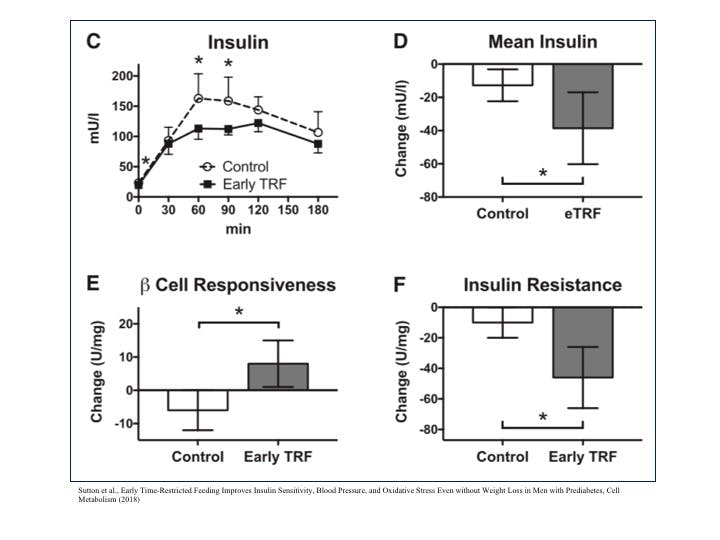

The benefits were noteworthy. Mean insulin levels dropped significantly, and insulin resistance dropped as well. Insulin is a potential driver of obesity, so merely changing the meal timing and restricting the number of hours you ate, and also by moving to an earlier eating schedule produced huge benefits even in the same person eating the same meals. That’s astounding. Even more remarkable was that even after the washout period of 7 weeks, the eTRF group maintained lower insulin levels at baseline. The benefits were maintained even after stopping the time restriction. Blood pressure dropped as well.

But doesn’t fasting increase hunger?

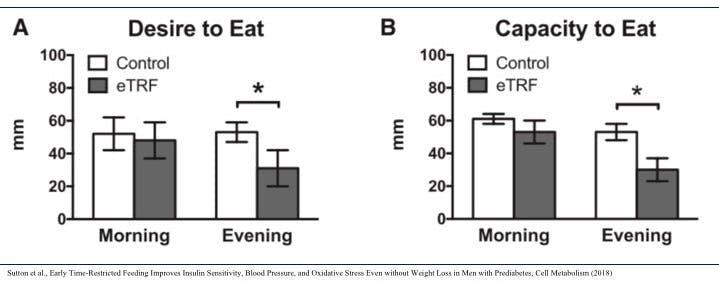

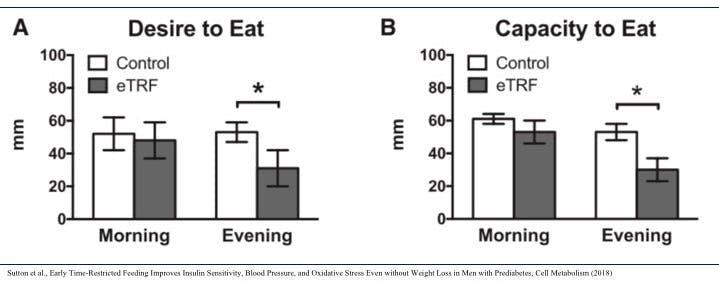

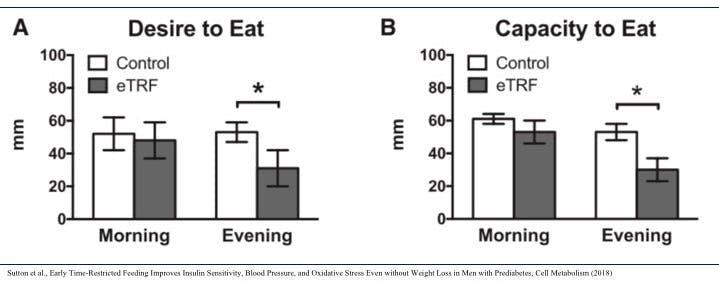

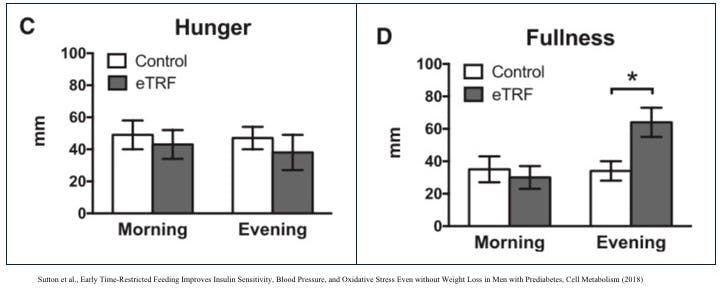

But won’t the time restricted feeding group be more hungry? Sure they might be skinnier, but their poor stomachs are growling for food in the evening, right? Incredibly, it was the opposite. Those people who restricted late night eating had LESS desire to eat, but also less capacity to eat. They couldn’t eat more at night even if they wanted to! That’s amazing, because now we are working with our body to lose weight instead of constantly fighting it. It is obviously easier to restrict eating in the evening if you are not hungry.

Somewhat counterintuitively, restricting eating at 2 pm produced more feelings of fullness in the evening. Some other important lessons learned is that there is an adaptation period to this method of eating. It took participants 12 days on average to adjust to this way of eating. So don’t start this eTRF strategy and decide it didn’t work for you after a couple of days. It can take up to 3 or 4 weeks to adjust. Most found the fasting period relatively easy to adhere to, but more difficult to adjust to the time restriction.

That is, it’s not hard to fast for 16 or 18 hours. But eating dinner at 2 pm is tough. Given the modern schedule of working or school during the day, we tend to push our main meal into the evenings. The main family meal together is dinner, and this is ingrained into us. So, I’m not saying this is an easy task, but it may certainly have a number of metabolic benefits. Having a fasting support group, such as the IDM membership community, can certainly help. Fasting aids, such as green tea, coffee or bone broth can also help (although some would not consider that a true fast).

But the bottom line is this. We focus nearly obsessively on the question of ‘What to Eat’. Should I eat avocados or steak? Should I eat quinoa or pasta? Should I eat more fat? Should I eat less fat? Should I eat less protein? Should I eat more protein?

But an equally important question lies almost completely unanswered. What effect does meal timing have on obesity and other metabolic parameters? Quite a lot, it turns out. Having a well defined fasting period is likely very important. The strategy of eTRF, and intermittent fasting more generally now gives exhausted dieters a new hope.

More

Intermittent fasting for beginners

Dr. Fung’s top posts

Intermittent fasting

More with Dr. Fung

Dr. Fung has his own blog at idmprogram.com. He is also active on Twitter.

Dr. Fung’s books The Obesity Code, The Complete Guide to Fasting and The Diabetes Code are available on Amazon.